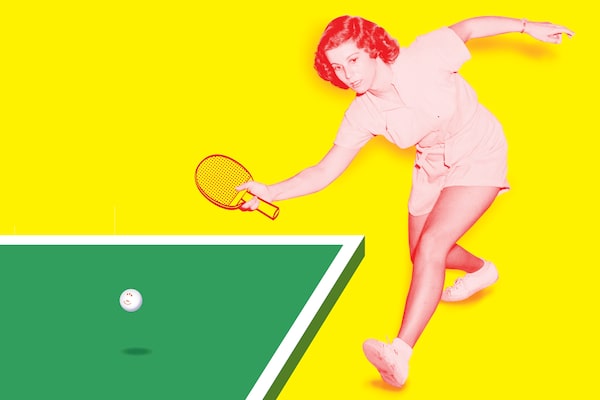

Illustration: The Globe and Mail. Source photo: Getty Images

Daniel Sanger is a journalist and writer based in Montreal. His most recent book is Saving the City: The Challenge of Transforming a Modern Metropolis.

I keep a list of things which are collectively underappreciated, and of which the virtues cannot really be debated.

When it comes to nature, these include bird song, the bizarre life cycles of mayflies and horsehair worms, the way an evening snowfall will slow and quiet down the world, the salutary effects of a plunge into cold water.

When it comes to cities, a good bicycle, wide sidewalks and trees – lots of trees, of all different species.

When it comes to sports and games, there is cross-country skiing. Skating on natural ice on lakes and rivers. Crokinole. But one stands out above all others: ping-pong (or table tennis, if you must). But while its status as sport or game can be hotly contested, as well as its chosen moniker, its prowess at knitting people together cannot be debated. It is democratic in a very pure sense, and at a time of increasing social division, what could be more welcome?

As a physical activity, ping-pong has few equals.

Studies have shown that it is one of the best sports for the brain, and not simply because your chances of suffering a head injury from a 2.7 gram plastic ball are essentially nil. Rather, since playing ping-pong requires all sorts of rapid-fire decision-making and processing of different types of information, it stimulates very disparate parts of the brain and increases blood flow as a whole. In this way, it helps develop new neural pathways which can slow down, possibly reverse, dementia and definitely help alleviate depression. Intensely played, it can also make you sweat and wonder, the next day, why you are so sore. “Chess on steroids” it has been called.

Another reason to love the game: It is as equal opportunity as a sport gets. Age, sex and physical condition are of virtually no consideration. As one enthusiast wrote, in ping-pong “dwarves topple giants, chubsters crush bodybuilders and wrinkled elders regularly whip whippersnappers.” Marty Reisman, perhaps the most legendary of American players, was winning medals at U.S. championships in his second decade as well as his seventh (the latter not in an old-timer category).

The sport is also tolerant of modest intoxication. A beer or cocktail or two won’t mess up your game in a perceptible way while a hit or two off a joint can have a truly felicitous effect. I still maintain that the best evening of ping-pong I have ever played was after trying out an odd contraption for vaping hash oil that the neighbour of my regular ping-pong partner had pressed upon him.

Ping-pong at Grossinger's Resort, Liberty, New York, 1977.Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Finally, if there is a sport other than, say, barefoot running or skinny dipping with lower barriers to entry, I’m not aware of it. If you can’t find a bat in your basement or attic, a perfectly adequate one can be bought for about $20, a set of four with net and balls thrown in for less than $50. And the game (or is it a sport?) can be played on any table of reasonable size. Indeed, when first dreamt up, there was no such thing as a ping-pong table – it was meant to be played on the supper table. (Pro tip: the smaller the table, the lower the net should be.) In a pinch, you don’t even really need a table. Chuang Chia-Fu, one of China’s first great players, honed his skills on the front door of his family’s home, which he would take off its hinges every morning and replace at the end of the day.

So ping-pong can help us all, even the most impecunious, live healthier and happier lives. What’s not to like about that? And perhaps, as a recent experience in my neighbourhood in Montreal suggests, it can even work as a societal lubricant and go a distance to building bridges and creating connections in this ever more diverse country of ours.

A note on the name: Those who take the game very seriously (and would probably object to it being referred to as a game rather than a sport), often react with a fatigued and/or irritated air to it being called ping-pong. “Table tennis, you mean,” a frustrated coach once told me. As a name, however, ping-pong predated table tennis for the … uh, activity. As did whiff-whaff, whim-wham, gossima and various other appellations.

It was only because the London toy manufacturer J. Jaques & Son had trademarked the name “ping-pong” that the International Table Tennis Federation was thus called when established in 1926. Otherwise the ITTF would have been the IPPF.

Less dignified, a bit déclassé perhaps, but as a name I much prefer the alliterative, onomatopoeic, two-syllable simplicity of ping-pong. (I like the term my cousins use even more: gnip-gnop. But we won’t start on that. Yet.)

Family ping-pong in the 1950s.Tom Kelley Archive/Getty Images

Like much of postwar suburban North America, I grew up playing ping-pong against siblings and friends in the basement of the family home when we didn’t have anything else to do and there was nothing to watch on the black-and-white Zenith. It was a pastime, a pass the time. The real sports were hockey and soccer or making smoke bombs with saltpetre and sugar. Then, of course, girls, weed, beer and music came along and ping-pong receded completely from my life.

The decentralized ubiquitousness of suburban basement ping-pong was, according to some, a principal reason that there is little serious table tennis tradition in North America. Not because the low ceilings preclude one of the game’s most delightful sequences – the defensive lob which follows a crushing smash and then leads to another crushing smash followed by another defensive lob and so on and so forth. Rather because people played on their own, in isolation, against limited competition, and tended to take the game for granted. If they wanted a game, they weren’t compelled to join a club where there might be a coach or a skilled opponent to teach them a thing or two. They just coaxed a parent/child/spouse/friend to come play downstairs.

I’m not sure what happened to that green, pressed-wood table with the sagging corners and ripped net in my parent’s basement. A garage sale probably. I have no memory of playing any ping-pong throughout my late teens or 20s. I never lived in residence at university or joined a frat.

I do, however, remember being very surprised, almost unable to comprehend, when an old friend of my father who was staying with us took me aside and asked very earnestly if I knew where he could find a table and a game. At that point, we were living in England and the man was a former African freedom fighter, in London to help negotiate the end of Rhodesia and birth of Zimbabwe. He had spent a long time in prison and played a lot of ping-pong. It was a revelation that anyone could need to play ping-pong, or at least pine to play.

That ping-pong found its way to impoverished villages in civil war China, a prison in Southern Africa in the 1960s, and became as international a game as soccer is thanks in large part to Ivor Montagu, an English aristocrat and oddball of the first order, a man who might have stepped out of a P.G. Wodehouse novel or Hilaire Belloc poem, but for his Stalinist sympathies and spywork for the Soviet Union throughout the Second World War.

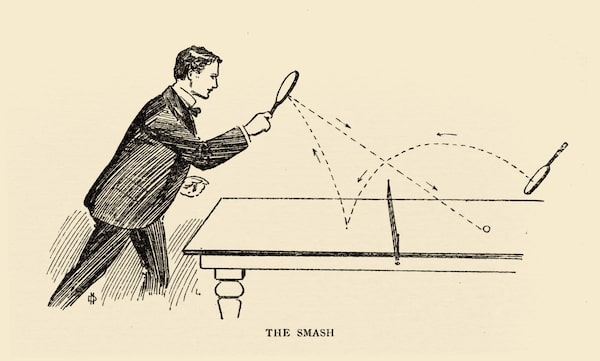

The game seems to have originated in the 1880s as a postprandial entertainment around some of the finer dinner tables in England, including that of Lord and Lady Swaythling, Ivor’s grandparents. Lawn tennis was by then a thing so it is hardly a leap to imagine enthusiasts of the game re-enacting the afternoon fun by carving a champagne cork into a sphere and using books or cigar boxes to bang it back and forth across the table. (Once, of course, the help had cleared the table off.)

The game caught on – but only modestly. Even if dedicated bats were manufactured with parchment or vellum faces, as on a drum, the problem was the balls. Whether made of cork or rubber, covered with fabric or not, they were too heavy.

Illustration from the instructional book Table tennis and how to play it, with rules, 1902Illustration by PUBLIC DOMAIN

Then in 1901 a British lover of the game came across a light hollow ball made of celluloid – an early plastic – while on a trip to the United States. He realized it would be ideal for the game.

The game took off around the world, Canada included. The go-to metaphor in written records was of an infectious disease. “Ping-pong is spreading in Canada generally with the rapidity of small pox in an unvaccinated … village,” the Victoria Times-Colonist reported in February, 1902.

Chicago suffered a severe shortage of balls that winter despite having received a shipment of 15,000 a few months earlier. A jesting headline in one paper read, “Got A Ping-Pong Ball? If So You Can Exchange It for precious jewels.” A few weeks later, a break-in was reported on swanky Lake Shore Drive by another paper. Six ping-pong balls were stolen but “the diamonds left undisturbed.”

Tables were set up everywhere, including the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa and the Supreme Court and Senate in Washington. Musicals were written about ping-pong. Cocktails concocted. Ping-pong cigarettes. Ping-pong parties. Ping-pong pies. Ping-pong pyjamas. It was used to sell everything. A condemned murderer in Brandon, Man., asked to spend his last afternoon before being hanged playing the game. He died serenely, it was reported.

Then, the bubble burst. Or, more appropriately, the mania burnt out like a celluloid ping-pong ball which has had a flame put to it. “Its sudden fall is one of the peculiarities of the sporting world,” The New York Times wrote before a year was out. “The tables are idle … It was one of the shortest crazes ever.”

All this occurred before Montagu was born. His parents never got rid of their tables – they had a big house in Kensington and more than one country estate – and, as the third and least athletic of three boys, Montagu found ping-pong was the only sport he could compete in.

Before he was 20, he had codified the rules – no one, it seems, had thought to do that before – and become president of Britain’s Ping-Pong Association. By then, he had been at Cambridge for three years (having been accepted at 15) and a fervent socialist for seven, which, if embarrassing for his nouveau riche banker family, led him to become chummy with HG Wells and George Bernard Shaw, among others.

Montagu never let his studies get in the way of ping-pong and was happy to use his family fortune and connections to promote it, whether in having tables made for the club he established at Cambridge or, at age 22, organizing the first world championship and setting up the ITTF, over which he presided for more than 40 years.

Montagu put his socialist faith and ping-pong passion together immediately. It was the perfect sport for the proletariat and the peasant, he determined, playable virtually anywhere, by anyone, at minimal cost. “I saw in table tennis a sport particularly suited to the lower paid,” he would write. An added benefit: His presidency of the ITTF provided excellent cover for fighting the good fight for socialism, as well as ping-pong, the world over.

Promoted by Montagu’s ardent internationalism, the sport made its way to some of the few places it hadn’t reached during the turn-of-the-century craze. Such as China, where it was a favourite of Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai both during The Long March and, later, when holed up in Shanxi province.

After the Communists finally took power in China in 1949, ping-pong had an inside track when it was time to decide on a national sport. Millions of yuan were thrown at it and when a Chinese player won the world championship in 1959, Mao heralded it as “a spiritual nuclear weapon.” Since then, Chinese players have dominated the sport in an almost suffocating way.

Mao Zedong playing ping-pong during the Long March in 1935.Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Some sports are made to be watched and are rarely played by their fans – American football, for instance, or car racing, if one must consider it a sport. Some are in the Goldilocks zone – good to watch, fun to play, such as tennis, hockey and basketball. Others are made to be participated in and don’t lend themselves to spectatorship. Cross-country skiing and, yes, ping-pong. Ping-pong just doesn’t translate to the small screen. The ball is too small and moves too fast. The rallies are usually too short.

And since our consumer society has always steered us toward spectator sports, the better to sell F-150s and such, the ParticipAction sports get short shrift.

A few facts about the game and its speed. A badminton birdie can travel as fast as 320 kilometres an hour when it comes off the face of the racquet, but loses speed very quickly. A tennis serve can hit 250 km/h and maintains its speed much longer – but the players are standing at least 25 metres apart. A ping-pong ball will rarely exceed 100 km/h, but the players are usually only three to five metres from one another. This means the hits-per-second rate in ping-pong is higher than in any other racquet sport and goes a distance to explaining all that blood flow to the brain and cerebral stimulation.

Efforts have been made to both slow the game down and speed it up in order to make it more attractive to spectators. The diameter of the ball was enlarged from 38 millimetres to 40 mm, which marginally diminished ball speed while slightly increasing the average rally length. Games are to 11 now, not 21 – and if they drag on beyond 10 minutes an incomprehensible “expedite system” comes into force. But even if the pandemic seems to have been good for table sales, no one will claim this has led to a ping-pong renaissance. The pickleball boom makes some promoters of ping-pong pickle-green with envy.

Army soldiers playing ping-pong in the barracks at Fort Brag in Fayetteville, North Carolina, in 1942.Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

But who cares whether ping-pong is attracting crowds to matches or converts by the thousands – it is, after all, a game to be played and enjoyed.

I began appreciating this again a bit late in life – circa 40 – at the cottage. There you do things differently. Bring water up from the lake in buckets. Saw and chop firewood. Use the wood to heat the stove upon which you cook porridge. Actually eat porridge. And at night read, or play euchre if there are four of you and someone remembers the rules.

Or, better, if your cousins are up, you paddle over to their place for some gnip-gnop. They don’t have a ping-pong table per se but they do have a reasonable facsimile – a dining table that is 8.5-feet long, instead of the regulation nine, and 3.5-feet wide, instead of five – with lots of room around it and even the possibility for high arcing lobs if you manage to avoid the log cabin’s tie beams.

On that table, many epic matches and multigenerational tournaments have been played, usually organized by my cousin John, who went to work in Romania for a Canadian telecom company in 1998 and has stayed there, but for the annual August pilgrimage back to Georgian Bay.

In Romania, anything involving tennis is taken seriously, including tennis played on tables, and in 2010 John told me a story about how a previously sketchy Bucharest park had been transformed by people coming together and batting a ping-pong ball across a table which had appeared from one day to the next.

At the time, I was working for the city of Montreal and we were overhauling a tired park which had a shuffleboard court and horseshoe sandbox which hadn’t been used, it seemed, since the early 80s. John suggested installing a ping-pong table or two.

I relayed the suggestion, the mayor liked the idea, the tables were a hit. Dozens of others have since been installed in parks and plazas in Montreal, as well as other towns and cities across the country. Even if wind is even worse than low ceilings for cramping the game’s style, in good weather there is often a cluster of people around them, playing, waiting to play, watching.

I never played much on the outdoor tables, but I did begin playing a decade or so ago. An engineer friend who also worked for the city got married, bought a house with a basement and then a ping-pong table to put in it. We began playing regularly in the evening, usually handicapped – or assisted – by beer, scotch or THC.

I also managed to distract my son, Antoine, from organized hockey for a year or two by enrolling him in serious table tennis – his was the coach who could not countenance the sport being called ping-pong. Vali was from Romania as well, and was a sweet if very serious man, tinged with a certain melancholy. Was it a broken marriage, I wondered, or perhaps the sadness of living in a cold, distant land, one which didn’t take his sport seriously at all? I never found out.

Antoine got pretty good, won a gold medal at the Jeux de Montréal in his age category, and announced that he had gone as far as he wanted to in competitive table tennis – he was going to play hockey the following autumn.

There was no negotiating. I missed the ping-pong tournaments that took place a half-dozen times a year at a high school in Laval, and that we would sometimes attend. There would be about 40 or 50 tables spread over three gymnasiums and players would come from afar – Manitoba, the Maritimes, the northeastern states. There would be wheelchair ping-pong and doubles ping-pong and seniors and kids and semi-pro ping-pong with $5,000 purses. There would be kiosks where you could spend a lot of money on ping-pong shoes, shorts, shirts and socks and having a bat assembled to suit your particular style of play – with the exact handle, blade and rubbers (forehand and backhand) you specified.

I did splurge on fancy bats for both Antoine and myself, but any fantasies I may have had about actually entering the tournament one day myself were kiboshed with the hockey announcement. I was back to basement and cottage ping-pong exclusively. Until last fall.

There is an arena near my home in Montreal’s Mile End neighbourhood which has not had any ice in it for years. Something to do with the refrigeration system – either it has been on the blink or uses an atmosphere-unfriendly gas, or both. Whatever the case, it’s a very costly repair job and the city has had better things to spend its money on.

In an inspired moment, however, our local councillors decided to turn the arena into an indoor playground and at that time of year when just such an escape is most needed – when each day is shorter, colder, greyer than the one before but abundant snow and its pleasures are still weeks away.

Lines were painted on the concrete slab of the arena, basketball hoops and nets for badminton and pickleball installed and, yes, three quality ping-pong tables appeared.

City councillors Richard Ryan and Alexander Norris playing on the first outdoor table that was installed in Montreal, in Parc Laurier, in May, 2012.Daniel Sanger

Immediately a community coalesced around them, and what a community it was. My first opponents were Mustafa, a Turkish-Canadian art director and Glauco, a Mexican cameraman. They usually played with Aonan, an Asian-Canadian film producer.

They were all good, in an amateur kind of way, but a different good than Eric, my engineer friend, and I were good, in our own amateur kind of way. Eric and I were all aggression, looking for any chance to put the point away with a hard forehand topspin or a backhand flick.

Mustafa, Glauco and Aonan were more strategic, more defensive with backspin chop after backspin chop dropping short over the net, offering little chance to their opponent to crush it. It was almost a different sport to master.

The next time I went to the arena, I found myself playing with Akhat who, I soon learned, was probably responsible for the tables in the arena in the first place.

Akhat grew up in Novokuznetsk, Siberia, and began playing in a club at 7 or 8. The teaching style was “Soviet boot camp,” in his words, with lots of repetitive drills. Because he is that way, he would complain, which meant the teacher just gave him the worst bat to play with. “I found it very annoying to learn to be good.”

Akhat stuck with it for a time and had a moment or two of glory – winning the Novokuznetsk city championship and such – but had quit serious competition by the time he was 12. For years, he only played very occasionally. Then in 2015 or so, he moved to Moscow to work for a big tech company and found that, like all good tech companies, it had a pair of tables. He got back into ping-pong and, because he is that way as well, started up a company club which soon had about 100 members.

After spells in Mexico and Toronto, Akhat found his way to Montreal a few years ago. He liked the outdoor tables he found in the city but they weren’t enough for him – there was the wind, of course, and you couldn’t play in winter. So he went to the public question periods at council sessions of the Plateau and Rosemont boroughs, and then to city hall, to ask for indoor facilities. Somebody, it seems, was listening.

As the slightly reluctant leader of the wonderfully diverse community of ping-pong players who descended on the arena, Akhat set up a Facebook group so that those showing up alone could be certain there would be others with whom to play. He organized doubles games when there were too many players, or just because. (Doubles ping-pong requires that players on the same team alternate hitting the ball so staying out of the way of your partner – and trying to tangle up your opponents – adds a whole other dimension to the game.)

After Akhat, I played with Mueed, who had been a serious player in Kashmir and who, even if he was out of shape and out of practice, had little trouble beating me four games straight. Then Sunny, small and slight and also unbeatable, at least for me, even if he was just as fond of that other great international sport, volleyball.

But my favourite opponent was Amani, a young Syrian engineer and human-rights worker, waiting for her refugee claim to be adjudicated. Growing up in Aleppo, Amani had played seriously as a child and became one of the top players in her age category in Syria. Different clubs tried to recruit her, but in her early teens her traditional parents made her quit the sport. They didn’t want her travelling to mixed competitions and said playing ping-pong wasn’t compatible with wearing a hijab. She stopped and only played on vacations to the beach or the mountains even if she missed what she calls “the cleanness, the classiness” of the sport.

Her family fled to Turkey when the civil war devastated Aleppo and, in the fall of 2021, she came alone to Montreal. Across the road from her apartment was Parc Pélican and in the park was a table where she met Akhat and others.

Daniel Sanger's friends, Amani and Akhat, play ping-pong in an arena in Montreal's Mile End neighbourhood.Daniel Sanger

When I play Amani, she is not all spins and slices and chops. Rather, she plays aggressively like Eric and I, hitting long, looping forehands, often from a metre or more behind the edge of the table. Rallying for fun, there is a metronome quality to some of our exchanges, the gnip, gnop, gnip, gnop, gnip, gnop of the ball hitting the table. The rhythm is hypnotic and even in the gloomy blue light of the echoey cavernous arena, it’s therapeutic.

But even if she is better than me, and certainly much more trained as a player, Amani tightens up when we first play games, rather than just rally, and I beat her. Competition makes her nervous, she says, stressed out.

I chide her and tell her to become a killer, like the best players. Like the writer Henry Miller, one of ping-pong’s great champions, or Bobby Fischer, the chess wunderkind, who was memorably described as “a remorseless, conscienceless, ice-blooded castrator” at the ping-pong table.

The next time we play, and the time after that, she has no trouble putting me in my place, just like most of the splendid group of new Canadians that this underrated activity has brought to this obsolete arena, allowing them to make connections with each other and even some old-stock like me. To create community, as they say, and the most important kind of community, that with strangers, the other, amongst us but usually not yet of us. Who would remain the other but for a small plastic ball with, at times, magical properties.