Photos: iStock/Public domain

Michelle Kaeser is the author of the novel The Towers of Babylon.

I don’t like this. That’s my first thought about becoming a mother.

I don’t like the crying, the squawking, the exhaustion, the breastfeeding. I don’t like the stress, the guilt, the profound boredom.

I look at my baby not with a dreamy gaze of maternal love, but through a veil of confusion and terror, and I don’t much like that either. It seems, actually, that I might not like being a mother at all. Uh-oh.

Day 1. I’d heard about the 100 days of hell, how the first three months are a nightmare. But when people spoke of this newborn phase, they also noted the bonding, the love, the great joy of it all. It’s a peculiar kind of torment that is liberally dusted with pleasures. Nothing like this circle of Dante’s Inferno I find myself in, waist-deep in a river of fire, forced to repent the decisions that led to this predicament.

Is it because the child is a pandemic baby? She was born in 2020, the most reviled year of the century. More ominously, maybe, she was born on 9/11. And more ominously still, she was born with a mark on her head. “The mark of the beast,” says my partner, though I prefer to think of her as a baby Gorbachev.

From the moment she entered the world, the child’s life has been clouded with bleak portents.

Little wonder then that motherhood, for me, isn’t getting off to a swimming start.

Or maybe this was just the wrong choice. I’d been ambivalent about motherhood all my life, forever back and forth on the matter until biology started to force a decision.

“So we’re doing this?” I said to my partner. I’d started noticing pregnant women everywhere, at the park, the beach, on the bus. They were all awash in a maternal lustre. I couldn’t seem to go a day without spotting one, shimmering like a divine signpost. “We’re really doing this?”

“We’re doing it,” he said.

So we got to the business of doing it, but as we neared the moment of possible conception, doubts flickered again. Our lives were propped up by a collage of jobs — an iffy financial situation. And what if I just wasn’t cut out for motherhood? I read a Murakami story once in which an insomniac mother looks in on her sleeping child and thinks, “I knew with absolute certainty that one day I would come to despise him.” That moment always resonated — would this be my fate?

The flickering doubts flared up and sent me leaping to safety at the last possible moment.

“What the hell are you doing?” my partner demanded.

“I don’t know! I got scared!”

“But we already talked about it. We decided.” My partner doesn’t have much trouble with major life decisions; he offloads that responsibility to God. But I’ve never managed a proper relationship with faith. It’s a continuing source of tension between us, and one that further enflamed my doubts. So I sat there looking at my maybe baby daddy, deliberating again: this path or that?

Day 9. Only Day 9! Time has warped and stretched. It drags along at the excruciating pace I remember from childhood, when everything was boring and seemed to take forever. Is this what parenting is — a regression to childhood? Without any real stretches of sleep, day and night have become meaningless conventions. It’s all just time, endless time in which I wonder how anyone in the history of humanity has ever taken care of a newborn before. I’ll never make it to Day 100.

There’s only one possible way through this crisis: TV. TV makes the time pass. It’s made decades pass with me hardly noticing. One tiny problem: We’ve resolved not to watch TV around the child.

“We don’t want her baby brain to turn to mush,” my partner says.

“Of course not.”

“We probably shouldn’t even have screens on around her.”

“Agreed. Absolutely.”

So I have to sneak TV while he’s sleeping. Or out doing errands. Or cooking dinner. Or in the shower. I fall down a Dave Chappelle rabbit hole, hoping that comedy will improve my mood, and stumble on an interview in which Mr. Chappelle offers his thoughts on dealing with the pandemic: “Just keep moving forward”; “The sun does rise in the morning”; “We find a way.” I repeat them hourly. Dave Chappelle, weirdly, has become my postpartum life coach.

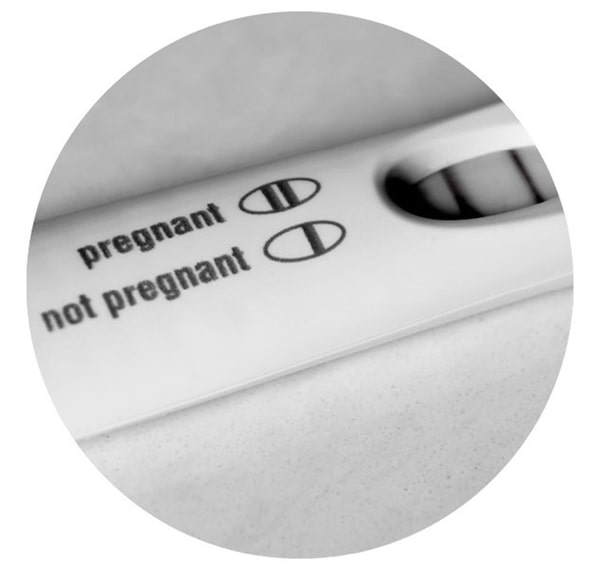

“I am so bold,” I said when the stick showed two lines: positive. I’d bit the bullet, and now here we were, sitting in the bathroom looking at a positive pregnancy test. “This is the boldest thing I’ve ever done.” But by the next morning, when I again saw that pregnancy test, which my partner had proudly displayed on our living room bookshelf, a very different thought took shape: I’ve made a mistake.

“You don’t seem particularly happy,” he said a few days later.

“Well, my life is over … and I haven’t done much with it yet.”

I’d sentenced myself to motherhood, servitude, years of preparing snacks and attending PTA meetings and darning socks, with no time left over to accomplish anything notable. All the pregnant women I saw on the street had lost their lustre. When I passed them now, they looked drab and burdened, and I felt only a sad camaraderie: We were all The Condemned.

There had to be an escape hatch. Maybe it was a false positive? But the pregnancy test instructions noted a less than 1-per-cent chance of that. Miscarriage? Seemed like a long shot, too. My thoughts bumped against the story of my grandmother who threw herself off a ladder while pregnant for the sixth time, hoping to shake that last baby loose. But even that didn’t work for her.

What worked for me, perhaps, was relentless negativity. I began to bleed a few weeks later, kicking off the long, but surprisingly understated process of miscarriage. Turns out you can be miscarrying while sitting through an all-day work meeting, commuting to and from the office, making chit-chat with friends.

It also turns out that miscarriage is no long shot. Stories of miscarriage started pouring in from family members, friends, acquaintances -- suddenly half the women I knew had had one, though I’d never heard a word about it. They observed an Omerta, a code of silence around it, for whatever myriad reasons. But now I wondered all the time: How many women was it happening to? How many of the women we see at the office, at the supermarket, on the bus are simultaneously losing their babies right in front of us?

The experience brought far less relief than I expected. But a month later, during a discussion about whether or not we should try again, I wondered if I’d been sufficiently devastated to warrant another attempt.

“You were hysterical,” my partner said.

“I was?”

“You cried for days.”

So there was the jam. I didn’t like being pregnant, and I didn’t like being not pregnant. What to do? In Marian Engel’s The Honeyman Festival, a heavily pregnant woman weighs the joys and sorrows of motherhood and arrives at this conclusion: “It appears that however one lives one’s life it is a mysterious kind of hell.”

The hell we chose was to try again. And this time we got the good news on New Year’s Day, like in some cheesy rom-com. This new pregnancy coincided with a new job, and a new home in a new neighbourhood, a great many changes for somebody who isn’t so bold after all. I felt that familiar sinking sensation, but my partner was excited enough for the both of us.

“2020 is going to be a great year!” he said.

Day 15. I want to die. The child barely seems human. She has some of the features of a human, but it’s a rough approximation at best. Her needs are relentless. Even when she’s asleep, I’m in a constant state of dread, knowing her next distressed shriek could erupt any second.

All this creature ever wants to do is breastfeed, but neither she nor I are any good at it.

“I want to quit this,” I say to my partner.

“But you’re a life-giving earth mother,” he says with a grin.

“That’s pure propaganda.” This isn’t the magical bonding experience I’d been led to believe; it’s a brutal, endless chore. In the moments of shallow sleep that I manage, I even dream I’m feeding her.

And yet sometimes, when I leave her for just a few seconds, to get a banana or turn on the radio, I forget about her altogether. I catch sight of her twitchy limbs in my peripheral vision and am genuinely startled: “What’s that? Who’s there?” Oh right. That’s my baby. I’m somebody’s mother.

I read about a similar phenomenon in Javier Marias’ novel All Souls. The narrator remarks that he sometimes forgets his son’s existence: “I mean that I forgot he had been born, forgot his name, his face, his brief past which it was my responsibility to witness. I don’t mean that I just stopped thinking about him for a moment, which is not only normal but beneficial to both, I mean that the child simply did not count.” Somehow this amplified level of parental absent-mindedness seems more tolerable in a father. Indeed, I keep thinking of myself as more suited to the role of traditional father, the kind of parenting that has a million built-in breaks.

All I need is a break. Just a few hours off. Maybe a day or two. Or a week. There’s a storyline in the TV show Insecure in which a new mom runs away from home, goes to a bar, drinks four margaritas and checks into a hotel. It’s meant to be a sad story about postpartum troubles, but at the moment it feels like a life goal. Or maybe it’s reasonable to be admitted to a hospital, just to be sedated for a stretch? Then I could return refreshed and ready to tackle this assignment with grace.

When a break finally comes, it takes a bad form:

“I’m taking the baby to church tomorrow,” my partner says.

“Uh …” We haven’t yet agreed on the child’s spiritual upbringing.

“I already signed us up,” he says to forestall further discussion. COVID restrictions have changed churchgoing. All are not welcome anymore. Only those who preregistered for a spot online, just as Jesus intended.

I object to exposing the child to the lunacies of the church, so I try to force myself to mount an opposition, but the possibility of a few hours alone is enough to override all ideological principle. So the next morning, while the family is off to worship, I laze around the house watching TV, like a delinquent father from a nineties sitcom. Like Homer Simpson. Perhaps that’s my optimal level of parental engagement.

I learned on the Real Housewives of Potomac that a baby born after a miscarriage is called a rainbow baby. I tried to think of that charming phrase every time I vomited.

“I think the puking is a good sign,” said my partner. “Must mean my seed is really taking hold.”

“Hm.”

“I have a good feeling this time.”

It’s easier to have good feelings when you’re not heaving several times a day, bringing empty clamshell containers to work as puke receptacles because your office only has one single-occupancy washroom.

“Why don’t you throw up into a garbage can like a normal person?” asked my partner, as I stuffed an empty arugula container into my purse.

“I can’t wash a garbage can five times a day. It’ll draw attention.” Tricky business telling your boss of two weeks that you’re pregnant.

The morning sickness soon passed, but a new sickness emerged. I’d heard murmurs of the new virus in December, news about its arrival in Canada in January, and by February I was anxious about going to work.

The effects of the coronavirus on pregnant women and babies were still unclear, but all I could think of was baby Fredo in The Godfather II, whose pneumonia in infancy always seemed like an offshoot of the Spanish Flu. And wasn’t there a link between his baby sickness and his adult Fredo-ness? What if my rainbow baby turned into a Fredo? A terrifying prospect.

But these concerned thoughts seemed promising. Amid all the wobbly feelings around having a baby, I was at least developing maternal instincts.

Day 28. I have no instincts for any of this. I am Ted Danson in Three Men and a Baby. A child has been dropped at my doorstep and I have no idea what to do with her.

I look to my mother for advice, but she’s too busy cooing at the baby: “Ooh, don’t you love this little schatzi!”

“Sure,” I say, although I can’t quite pinpoint the love. It must be lost behind the sheath of exhaustion and dread and regular weeping.

My mother is the only visitor we get. This child is socially distanced. There are no plans for her to meet aunts or uncles or cousins or friends or other givers-of-advice. A lonely start to life, and to motherhood. So I’m forced to seek parenting help in the one place I swore I would never look: the internet.

I Google everything. I even tentatively venture onto message boards, hoping to find some like-minded mothers, but instead I find the abbreviations “DD” and “DS.” It takes me days to work out that these mean Darling Daughter and Darling Son. As if these people are going to cop to hating motherhood!

But others do. Word starts to trickle in.

“I was Googling ‘what if you don’t love your baby,’ ” a friend texts me.

“It took a good six months before I even liked my second child,” another e-mails.

A public health nurse calls and advises me never to shake my baby, this presumably a common enough occurrence to warrant phone calls about it to all new mothers in the city.

Even my own mother says: “At the very beginning, I did wonder if I’d made a mistake.”

“Why didn’t you tell me that?” I ask.

“Well … you don’t say that to people,” she says. Another Omerta.

Lockdown started a few months into the pregnancy, and I, like everyone else, went remote. A solitary pregnancy then, with almost no friends or family to witness it, almost a secret pregnancy, like I was an unwed teenager shipped off to a maternity home.

No matter. My ambivalence about the baby was finally waning, replaced with a growing tranquility. I would lean into the pregnancy without the distraction of the outside world. I would calmly embrace this rare opportunity to go to seed. I stopped changing my clothes and brushing my hair and shaving things; I watched with fascination as my body returned to the wild. There would be no cute maternity outfits, no baby showers. With the exception of midwifery appointments, I rarely had to bother leaving the house.

“Do you have support lined up once the baby is born?” a midwife asked me at one of these appointments, from which my partner had now been COVID-banished.

“Sure,” I said. “My partner is going to take a couple of days off.”

This was an insufficient answer, it seemed. She put her hand on my knee and looked at me with grave concern. “You should think more about that. You’ll barely have time to take a shower.”

Should I tell her I’m only averaging a couple of showers a month anyway?

Nothing fazed me. In War and Peace, Tolstoy describes “that special expression of an inward and happily serene gaze that only pregnant women have.” A similar sentiment is echoed in an episode of the Real Housewives. And as the pregnancy progressed, despite the pandemic, I became a walking embodiment of this serenity.

I lost one of my jobs to COVID; no problem. The pandemic killed all five of my partner’s jobs; I kept my cool. Propelled by this growing tranquility, I even resolved for a home birth.

“That’s preposterous,” my partner said. “We’re not hippies.”

“It’s probably safer than a hospital right now.” Home-birthing would allow us to dodge the contagion of hospitals altogether. “And the midwives will be here the whole time.”

“But they’re not doctors. What if something goes wrong?”

What could go wrong? I was transforming into a life-giving, maternal goddess. The quiet peace of our new home would be the ideal setting to usher in new life.

Day 57. My home is a prison. Once again, life coach Dave Chappelle’s musings on the pandemic are strangely applicable to motherhood: “People are stuck in a house with their choices. Do you like your house? Do you like who you’re with? Do you like these things you’ve accumulated? I hope you like ‘em. ‘Cause you’re stuck with ‘em.”

No, I do not like these things I’ve accumulated, this mountain of baby crap I tried so hard to avoid. And I’m tired of these people I’m with! This guy, this baby, this visiting mother.

“The baby will do something new every day now,” says my mother, still delighted by the baby’s every twitch.

Not true. Every day is almost identical to the one before. I beg the child to do a new trick. Instead, as usual, she barks for me to hold her face down because she likes to study the wood floor and the living room rug — but God help us if I venture into the carpeted bedroom. As I trace endless zigzags around the living room, beholden to the child’s singular interest, I look into the neighbours’ homes, where TVs are on, beckoning to me. To the east, a couple is settling in for a day of nature documentaries; to the north, a guy is bingeing RuPaul’s Drag Race. I am overcome by burning jealousy.

If I can’t sit around watching uninterrupted hours of TV, then I want to do something, see someone, go somewhere. But there’s nowhere to go! Baby and me groups are closed. Story time at the library is closed. Dear God, even the churches have closed now. This is pandemic life. You’re not supposed to go anywhere or do anything. You’re supposed to just sit at home with your family and look at each other.

“How much longer can this go on for?” I ask my partner.

But what does he know? What does anybody know? Not even our leaders know anything. In a live address, the Prime Minister says encouragingly, “We need to stay strong and hang in there a few more months,” but then he tilts his head to the side and casually adds “… maybe more than that.”

“‘Maybe more than that’?” I shout at the screen.

“I’m not happy about it either,” says my partner. “When are we going to have her baptized?” Baptisms are over now, too. The child will end up in the Inferno with me, in the first circle, where the unbaptized end up as wandering shades.

What’s going to become of these pandemic babies? They are all subjects in this grand social experiment, living lives of strict isolation, developing a mortal terror of other humans along with their more basic skills, like holding up their heads and using their hands. What are the effects of only ever seeing the same few human faces for your earliest months, years … maybe more than that?

Labour started late in the evening, while my partner and I were watching season two of the Danish political drama Borgen. That I had made it through the whole first season of this mediocre mess was another testament to my perfect serenity.

I was eminently prepared for the homebirth: I had collected old towels, arranged a few candles and watched several birthing videos scored with calming, new age music.

As the night turned to morning, and the intensity turned to crazy, my partner dutifully timed the contractions, waiting for the specific pattern that meant it was time to bring in the midwives.

“Contractions are still five minutes apart,” he said late in the afternoon. “We’re supposed to wait until they’re three or four minutes apart.”

“Right. Okay.” But then why could I feel a head in my pelvis?

He called the midwives a few minutes later, but by then I was already on my hands and knees in the bathtub, reaching down to find the top of my baby’s head. The next time I looked down, it was because something gave out and I heard a plop in the water, and there in the tub appeared a baby, wet and squirmy, no medical professional in sight.

“Hm,” said one of the midwives when she arrived later and assessed the damage. “How are you feeling?”

A complicated question. I felt strangely detached from this newborn creature, reluctant to hold her. I felt shellshocked and exhausted. I also felt rather dizzy.

“Um …,” I said, and then fainted on the bathroom floor.

So our new family wound up at the hospital, where some kindly doctors dug blood clots out of me, a brutal enough procedure that it was accompanied by a cocktail of fentanyl and laughing gas. This wondrous gas brought me my first moment of peace since the onset of labour, but my partner was the one laughing.

“What’s so funny?” I asked.

“You went through 22 hours of labour with two Tylenols, because you wanted this hippie homebirth experience, and then you end up all doped up in the hospital anyway,” he said, smiling down at the bundled baby in his arms. “Goes to show … God has a sense of humour.”

But the real cosmic joke must be this: When women have been kept awake for days, enduring the unique torment of labour, when they are beyond exhausted, very sore and most in need of quiet rest, it’s at this exact moment that the universe dumps a needy, screaming infant into their laps and shouts: Now get to work!

Day 100. I study the child for some grand shift that signals the end of hell. She stares back at me, then shrieks into my face.

I recognize this cry: boredom. I want to make the same sound myself dozens of times each day.

Over the past 100 days, I have learned to pick out the nuanced meanings of her astonishing array of cries. This seems no less miraculous than learning to decipher a dolphin’s clicks. But among all her strange noises, distressed tones have become a minority. More common now are joyful squeals, triumphant screeches and something very close to genuine human laughter. Over these 100 days, in fact, the baby has stealthily developed into an identifiable human.

Perhaps, then, we’ve clawed our way out of the Inferno after all, though we’re still a long, long way from heaven. I suppose that puts us on the shores of purgatory. But everyone’s in purgatory at the moment. We are all stuck in Pandemic Purgatory, our lives collectively stalled, awaiting some grand salvation that may or may not come.

The child announces her boredom again, loudly.

“Yes, I know you’re bored, baby,” I whisper and gently rub her back. “But we’re all bored right now. That’s just part of pandemic life.”

I’ve heard that women are programmed to forget the pain of labour so that they’ll brave the ordeal again. The same must be true for the newborn phase. Because what kind of maniac would put themselves through this with a lucid awareness of its horrors?

Already now it takes some work to remember the first night home from the hospital, when I stared at the child with blank terror, or the unhinging effect of that first stretch of sleepless days that had me daydreaming of disappearing into the ocean. Sometimes these memories turn so dim that it seems almost possible to do it all over, fill the house with these strange creatures that morph into humans.

“You want to have another one?” my partner asks me.

I look at the child; her expression is inscrutable. Is she about to puke? To cry? To send another howl up to the heavens? No, instead here comes an adorable, full-faced smile.

“Another one?” I say and tickle the baby’s little cheek. “Not a chance in hell.”

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.