Mellissa Fung is a Canadian journalist.

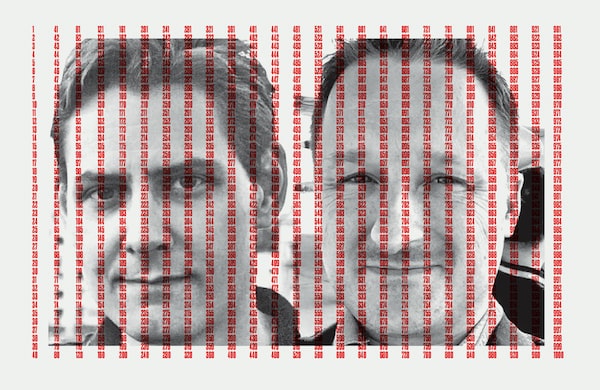

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: BRYAN GEE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Thirteen years ago this October, while reporting on conditions for women at an IDP camp on the outskirts of Kabul, I was kidnapped and held hostage for a month. My story has been told many times – too many times, at least in my view – at the expense of the more urgent ones that need telling, especially about the people in Afghanistan.

So I’ve had a lot of time to reflect on the notion of captivity. I made a documentary called Captive, about the plight of girls who had escaped from Boko Haram’s camps in northeastern Nigeria; I’m following that up with a book expanding on the topic. I wanted to explore how they cope with trauma; how girls who started with so little to begin with come back from such a horrible ordeal. I wanted to know how captivity changes you; how it changes others’ perceptions of you; how it changes your perceptions of things around you.

The girls and I discovered we had a lot in common, despite our obvious differences in circumstance. I’ve concluded that once held captive, you are always a captive. The experience of being held against your will, the loss of control around your very survival, the guilt you feel at the anguish of your loved ones at home – every emotion you usually try to keep at bay suddenly comes alive, screaming in your mind. Rage, fear, despair.

The girls were held in the Sambisa Forest in Nigeria; I was held in a hole in the ground in Wardak Province. Both were dark, dark places. And we have all brought some of that darkness back with us. The forest manifests itself in the girls’ struggles to reintegrate. And the hole is a place inside me now – one that I try never to revisit, even when it beckons every so often.

Chinese newspaper claims Michael Spavor photographed Chinese military equipment

Chinese ambassador to Canada denounces Meng Wanzhou’s ‘arbitrary detention’ as 1,000-day mark nears

I can’t imagine how Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor are coping as they now mark an awful milestone: 1,000 days in captivity. I can’t imagine being held against your will for so long. Are they even marking the days anymore? How are they pulling themselves back from the abyss of despair? How are they coping with the loss of control over their lives? How are their families coping? How dark will that hole be for them, when they are finally allowed to return home?

My heart hurts for them and their families, who bear an unfathomable burden. I know this because my captivity is still a difficult subject for my family. I can’t know their pain, but I feel responsible for it – and they have to deal with it anew whenever the darkness pulls me back.

And it has been pulling me back over the past month, ever since the Taliban began its march across Afghanistan. I’ve been working around the clock with a network of other like-minded women to try to help friends and colleagues who are now in danger as the Taliban reimposes strict rules on women. They are all begging us to help them leave, and we are trying as hard as we can – but we are running up against bureaucracy, red tape and logistics. Some days, it feels as hopeless as it felt in the hole. And so the rage, fear and despair that I brought back from that dark place are finding new life in me.

It takes all the strength I can muster not to be dragged back there; I will admit, it is a struggle right now. I have more or less abdicated my responsibilities as a spouse, a friend, an author and a co-worker. I do not even begin to know how to apologize for my absence. I am breaking inside, watching a country and a people fall into a hole I can’t seem to rescue them from.

This is not the person I want to be, especially for those who love and care about me. But it is a part of me now that I must wrestle with. Trauma’s scars run deep, and its triggers are many.

And so it will be for the Michaels, whenever they come home. They will not be the same Michaels they were before. When you come back from captivity, you come back a different person; some part of the former self is missing, replaced by something darker, a part of the self that has suffered the inhumanity of being held hostage and whatever depravities your captors wrought on you. Knowing what I know, it hurts to even think about their treatment over the past 1,000 days.

But we can’t lose hope that they will return. And when that time comes – and let’s hope it comes sooner than later – we must wrap our arms around them and their families. We have to give them everything they need to fully come back from the darkness.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.