When Rover goes to the vet feeling poorly, his problem often has to be diagnosed using a lot of guesswork and intuition.

Since pets can’t use human language to say what’s wrong, vets need help – help that is beginning to come in the form of artificial intelligence (AI).

From vets’ offices to law firms and beyond, AI is fast becoming a superhuman, instant research assistant that professionals can turn to for the most up-to-date information they need to do their job.

Veterinarians work in an environment that makes a virtual research assistant particularly attractive, says James Carroll, the president and CEO of LifeLearn, a Guelph-based startup.

“You don’t know what species is going to walk through the door,” says Carroll, whose firm has developed an artificial-intelligence assistant for veterinarians, called Sofie.

In addition, most of them work in small clinics and, unlike doctors who treat human beings, vets can’t refer their furry patients to specialists. “There’s not a radiologist down the hallway,” Carroll says. “There’s no cardiologist that’s available.”

That means that vets have to treat a diverse range of conditions − at every stage − in a diverse group of animal species. That requires a massive amount of specialized knowledge.

When vets don’t know something, they often turn to books, but that takes time and doesn’t account for new research. Internet searches are a poor substitute, often including results from questionable sources, rather than peer-reviewed journals.

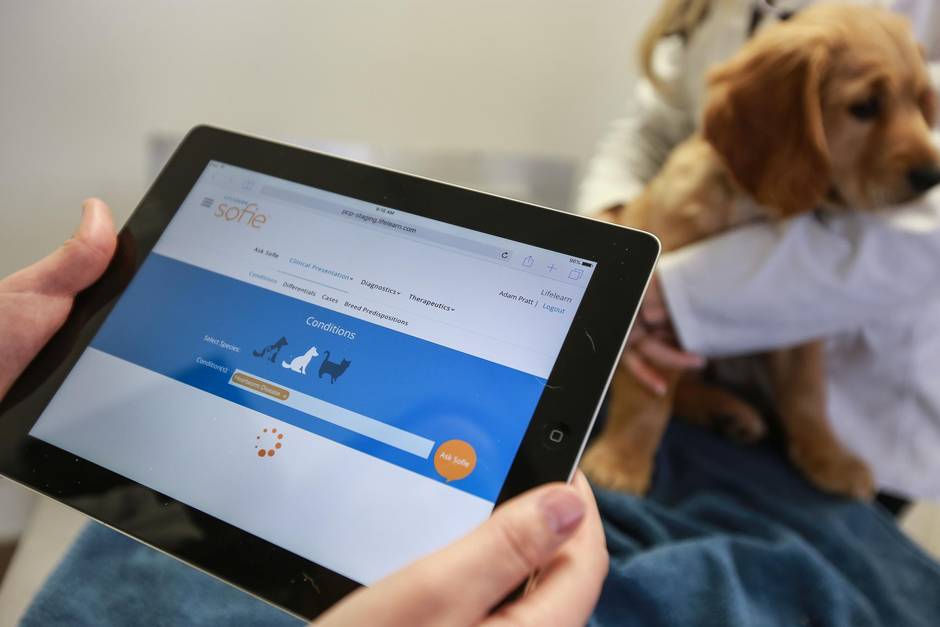

That’s where Sofie comes in. It’s a mobile application that gives answers to natural-language questions based on their specific context.

“You could literally type in to your iPhone ‘what are my best treatment options for a dog with pancreatitis and elevated heart rate?’, and we provide a set of hypotheses based on the context around that question and the relevance of the content,” Carroll says.

There’s a deep database powering Sofie’s answers.

“As of today, we’re at a point now where Sofie understands over 800 medical conditions and cancers, based on a knowledge set of just north of 44,000 pages of research and veterinary medical literature,” Carroll says.

Underpinning it all is the natural language processing abilities of IBM’s Watson, an augmented intelligence system (also known as cognitive computing), designed to answer questions based on how people actually speak.

A veterinarian could ask Sofie about treatment options for a specific condition in a specific type of animal and get several hypotheses based on the context of the question and the relevance of the results, Carroll says.

Initially, that was done manually; a team of veterinarians and experts mapped connections between the massive amounts of data that were being fed into the system. Now, though, Sofie is also learning from its users.

“We see what results vets are choosing,” Carroll says. He thinks the most interesting application of Sofie is its ability to help vets provide more proactive care.

Say you bring your healthy two-year-old dog to the vet after just coming back from a vacation where you took the pooch hiking. You might be asked to fill out a short survey that’s synced with Sofie before the appointment. Based on that information, the application can alert the vet to diseases spread by ticks in that region. Or, based on the genetic predisposition of your dog’s breed, it might make recommendations help avoid common conditions.

“These aren’t things that are front-of-mind for a vet looking at a healthy dog,” Carroll says.

What sets Sofie apart isn’t just the ability to understand natural language. It’s also the ability to process unstructured data − information that was intended to be read by people rather than computers. “Our ability to harness that unstructured data is key to everything,” Carroll says.

Dianne Pillitteri, a Burlington, Ont.-based veterinarian who is one of the first to use the app, says she likes what she's seen so far.

"Sofie provides me with immediate access to relevant, evidence-based information, resources and tools when looking for information on any particular case," she says.

Powering that ability is Watson.

“Today, computing has moved beyond just the tabulations and programming and rows and columns, to all the unstructured data,” says Sin Graham, IBM Watson solutions leader for Canada.

She says that in the past, computers could only process data that was organized in specific ways − in rows, columns and tables. That’s changed. “We’re at a stage now where we can take unstructured data, so information, just how you and I talk,” can be fed directly to the Watson system, she says.

As it learns about a specific subject, it’s able to process data faster and more accurately.

Artificial intelligence already plays a bigger role in our lives than we might realize, says Ali Reza Montazemi, a professor of information systems at McMaster University’s DeGroote School of Business. It’s in our cameras and it’s what powers online searches.

He describes unstructured data as information without a fixed answer. “For example, ‘the weather is warm,’ has a different connotation for me than for you,” he says. “You use your intelligence based on your background and knowledge to come up with an answer.”

This unstructured data accounts for the majority of information, even online. “About 80 per cent of the data that we have is unstructured,” Prof. Montazemi says.

Computers can understand this data through something called fuzzy logic, a way of sorting information into groups based on degrees of similarity rather than exact matches. “In the real world, most of the things aren’t heads or tails,” he says.

That sorting mechanism, repeated thousands or even millions of times, allows computers to deal with much more complex problems than in the past and it’s been enabled by the increase in processing power, coupled with the declining cost.

It’s technology like this which allows Watson to understand not just the context of a search but even the intention and tone or the questioner.

This is why AI is becoming a perfect technology to take on the role of research assistant, IBM’s Graham says.

This content was produced by The Globe and Mail's content studio, in consultation with IBM. The Globe's editorial department was not involved in its creation.