Canada got one of its first tastes of installation art in 1969, in the street-front window of a little house on Toronto’s Gerrard Street West.

The house’s tenants were three young, unemployed artists who would entertain themselves by creating fake store displays in the window.

“Eventually these grew from being just in the window to taking over the whole living room,” recalls one of those artists, AA Bronson. “And infamously, there was always a sign on the door that said ‘Back in five minutes.’”

The mischievous trio – Bronson, Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal – became the underground collective General Idea and the godfathers of Canadian installation art.

Today, their work is housed in the National Gallery of Canada, while Bronson, the group’s only surviving member, is internationally renowned for his own installations, which have been known to occupy entire galleries.

And the installation concept itself has also moved from the fringes to centre stage, claiming more and more space – quite literally – on the global scene.

Art Basel in Switzerland, the world’s preeminent arts fair, now devotes a building the size of an airplane hangar to large-scale installation art under the apt banner “Unlimited.”

This year’s show included work by such heavyweights as Frank Stella, Anish Kapoor, Tracey Emin, Canada’s own Stan Douglas and Bronson himself with his recent piece Folly.

Although they may not have the budgets of those superstars, emerging artists are also working in the form.

Last year’s edition of the Bombay Sapphire Artisan Series, a contest dedicated to discovering emerging visual artists, saw at least one installation work competing in each of the 16 U.S. and Canadian cities involved.

“In previous years, we’ve had installation pieces that have won the overall competition,” notes the series’ Chicago-based curator, Andre Guichard. That’s not surprising, given current trends.

“Right now, installation is what’s happening in the art world,” he says, and as such, the competition encourages submissions of all genres of visual art.

For artists, part of the appeal is that installations can embrace all the other forms of artistic expression, from painting and sculpture to video and performance. “They can encompass so much,” says Bronson during an interview from his home in Berlin. “They can be such rich territory.”

They also invite the sort of collaboration that Bronson still thrives on. In 2015, he oversaw a pair of twinned gallery installations in Austria, AA Bronson’s Garden of Earthly Delights in Salzburg and AA Bronson’s Sacre du Printemps in Graz, which involved multiple fellow artists and featured everything from imaginative variations on Zen gardens and Buddhist mandalas to a performance based on Hebrew ritual by Winnipeg’s Michael Dudeck – all of which reflect Bronson’s highly individual approach to spirituality.

Another reason artists are attracted to installations is that they offer the opportunity not just to showcase artworks but to transform the space in which they are displayed.

“The space itself becomes a medium and a tool to work with,” says young Toronto sculptor Michael Vickers. In the last few years, he and his creative partner, video artist Oliver Pauk, have devised a string of collaborative installations for such events as the Toronto International Film Festival and Nuit Blanche.

The pair combines their disciplines in designing environments that often involve suspended sculptures and digital projections, resulting in an otherworldly effect.

“The goal is to bring people to another place that seems foreign to them, a separate world that we’ve created,” Pauk says. “When you step into this space, it really transports you somewhere else.”

Installations, however, can present a challenge to galleries and museums. Exhibiting them is often not as simple as hanging a painting or mounting a sculpture.

Guichard points to a few pieces in this year’s Artisan Series that required extra care – or muscle.

Simply Sapphire – Melted, Not Stirred, a blown-glass chandelier made of wine, beer and gin bottles by Santa Barbara artist Seth Brayer, was so delicate that Guichard says assembling it (under the artist’s supervision) was “probably an eight– to 10-hour process.”

A gentle touch was also needed when installing Lego Vuitton Don by Brooklyn’s Jimmy Jenkins Jr., which consists of Louis Vuitton luggage intricately reconstructed out of Lego blocks.

Conversely, a lot of heavy lifting was involved in mounting Jordan by Seattle muralist Joe Nix, a large portrait painted on uneven poplar planks that weighs more than 200 pounds.

The added headaches are worth it, though, Guichard says. “Not to take anything away from traditional or two-dimensional art, but installation art allows your mind to imagine and see things differently,” he says.

He compares its effect on spectators to that of a joke with a delayed punchline. “It draws you in and then you suddenly get hit with the meaning – boom! That’s what I like about it.”

It also lends itself to incorporating the latest technology and capturing the zeitgeist.

“We’re seeing a lot of it related to social justice right now,” Guichard says, “to things that people are talking about in social media.”

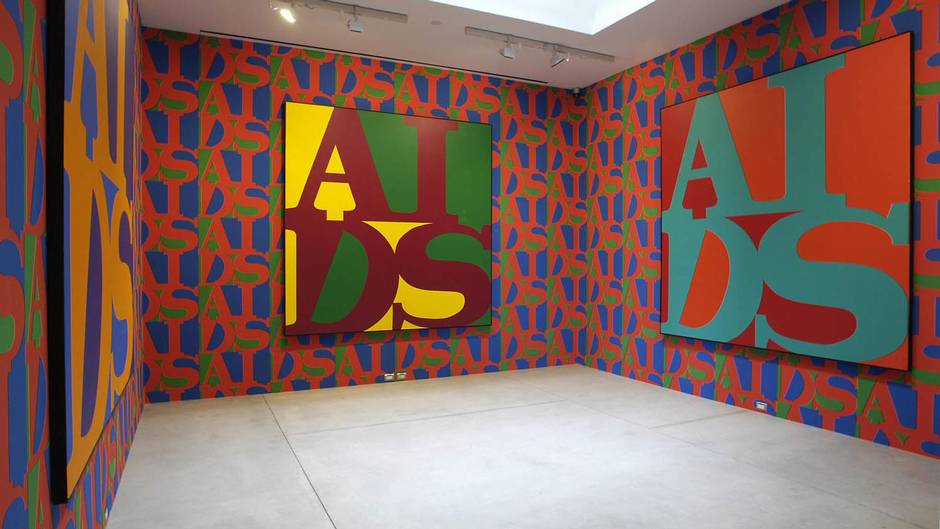

Decades ago, General Idea famously used it to comment on and satirize commodification and consumerism – and then later to raise awareness about the AIDS crisis.

It can also bring a fresh perspective to the past. Vancouver’s Geoffrey Farmer, one of the hottest installation artists today – and Canada’s representative at the 2017 Venice Biennale – has won acclaim for such works as the photo sculpture Leaves of Grass, a massive retrospective collage of old Life Magazine images, and the mechanical puppet piece Let’s Make the Water Turn Black, which was inspired by the 1960s music of Frank Zappa.

Bronson is a fan of Farmer’s work, but when asked to predict the future of installation art, he demurs.

“I think it’s going in a hundred directions at once,” he says. “It’s one of those things that’s constantly mutating.”

There has, however, been one big change in recent years: institutions are no longer the only ones buying it.

“There are now private collectors collecting large-scale installations,” Bronson says, “and that’s something new.”

This content was produced by The Globe and Mail's Globe Edge Content Studio, in consultation with an advertiser. The Globe's editorial department was not involved in its creation.