A consignment shop and small church in the town square of Celina, Tenn.

Martin Cherry/The Globe and Mail

On June 7 in Toronto, The Globe and Mail is holding a live panel discussion, Globe Talks: NAFTA in Play, on the future of trade with our biggest partner, featuring Globe journalists Barrie McKenna and Joanna Slater with experts Dan Ciuriak, Laura Dawson and Michael Kergin. For details and tickets, visit tgam.ca/NAFTA

When Kenneth Masters was growing up in the twisting valleys of northern Tennessee, families lived off the land. Many grew tobacco and brewed moonshine. He still remembers the arrival of electricity – a single hanging bulb – when he was five years old.

In 1953, OshKosh B'Gosh Inc., a Wisconsin clothing company, opened a factory in his hometown of Celina, which sits near the confluence of the Obey and Cumberland rivers. Less than a decade later, Mr. Masters joined the company as a 21-year-old stock boy.

Celina became a booming little place. Each afternoon, local traffic would back up for miles after the end of a shift at OshKosh. Workers could walk up a small hill to town to shop at stores selling dresses and shoes – "nice enough clothes to see the president," one employee recalls.

For more than four decades, OshKosh was the mainstay of the town and surrounding Clay County. Mr. Masters rose from stock boy to manager of the Celina plant to vice-president of manufacturing for the whole company.

Then came the North American Free Trade Agreement.

In 1996, two years after the trade pact took effect, OshKosh closed its plant in Celina, putting hundreds out of work. The company's total number of employees in the area eventually fell from about 2,000 to zero.

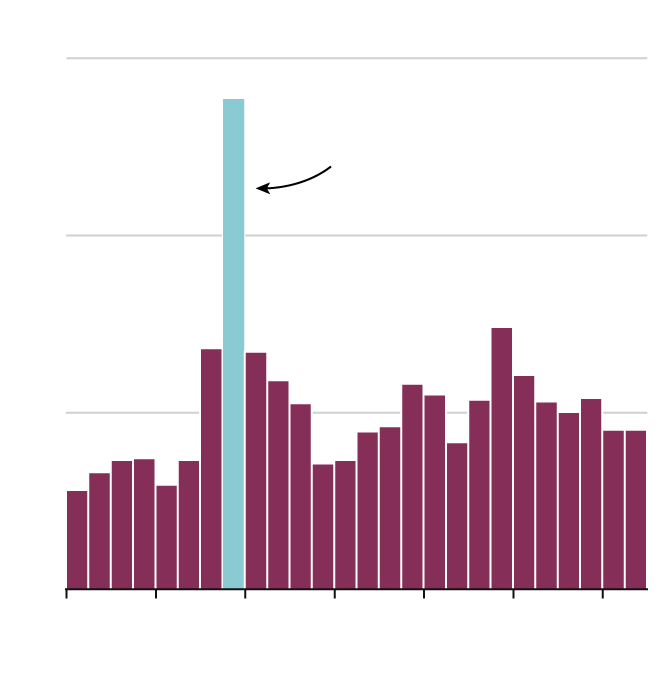

Clay County jobless rate

30%

Annual average

Year after

OshKosh’s

departure

20

10

0

1990

1994

1998

2002

2006

2010

‘14

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: TENN. DEPT. OF LABOR

AND WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

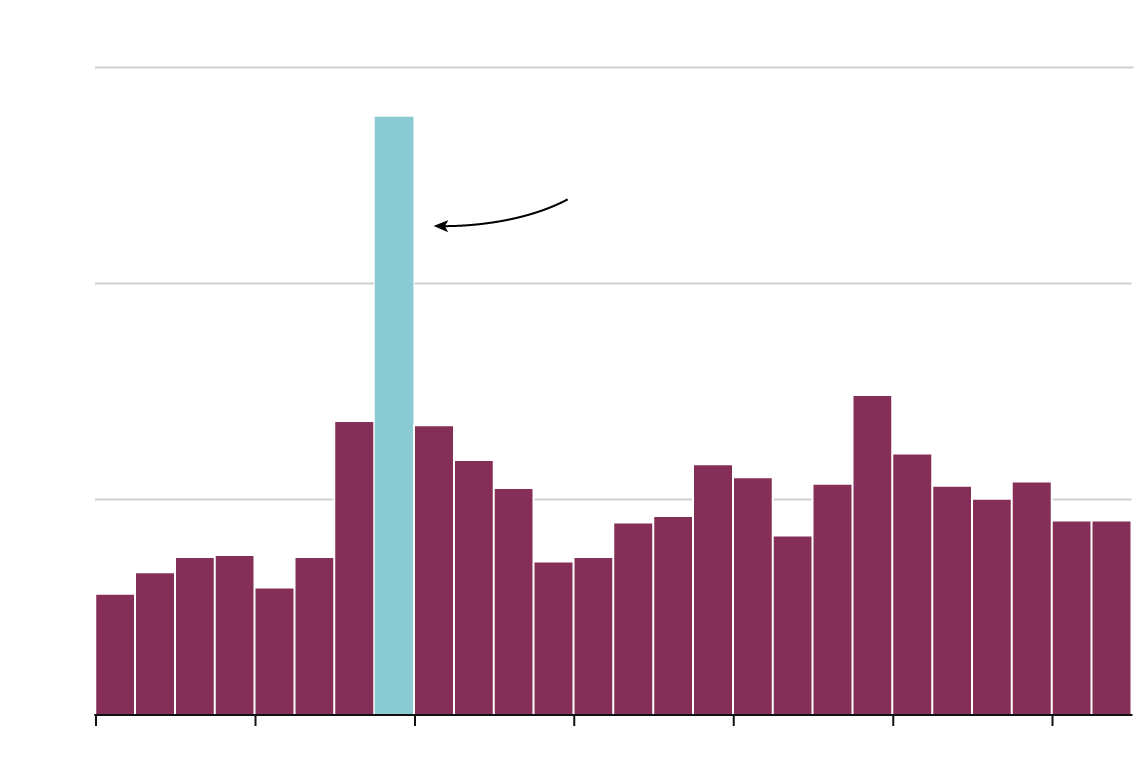

Clay County jobless rate

30%

Annual average

Year after

OshKosh’s

departure

20

10

0

1990

1994

1998

2002

2006

2010

2014

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: TENN. DEPT. OF LABOR AND WORKFORCE

DEVELOPMENT

Clay County jobless rate

30%

Annual average

Year after

OshKosh’s

departure

20

10

0

1990

1994

1998

2002

2006

2010

2014

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: TENN. DEPT. OF LABOR AND WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

"I was there at the birth and at the death," Mr. Masters says of his role in expanding OshKosh's factories in the region. "I opened them and I held the funerals."

The most comprehensive trade deal of its era, NAFTA helped reshape a continent's economy, but ultimately was neither the boon its proponents had promised nor the nightmare its opponents had feared. In the view of many economists, NAFTA's impact on the U.S. was moderately positive or somewhat mixed.

But the picture looks different in places like Celina. Here, NAFTA remains a painful subject – and the story of these communities is what generated the push to renegotiate the deal in the first place. Now many locals are looking to U.S. President Donald Trump to make good on his promises to help turn back the clock.

As recently as last month, Mr. Trump called NAFTA a "catastrophic trade deal." He vowed to negotiate "very big changes, or we are going to get rid of NAFTA once and for all." So far, however, the Trump administration appears to be seeking modest changes to the agreement. Formal talks could begin as soon as mid-August.

Root hog or die

Celina (pronounced Suhl-EYE-na) is about a two-hour drive from Nashville. But while the state capital is experiencing an economic resurgence – driven by the entertainment, health-care, tourism and auto sectors – Celina struggles to generate jobs.

More than two decades after the passage of NAFTA, if you ask people here what they think of the trade deal, the response is invariably negative. NAFTA is synonymous with "jobs that went south," says Joann McLerran, a local teacher. "It killed us," says Sandra Wix, the director of the county's seniors centre, with a grimace.

"It ruined a lot of families," says 77-year-old Glenda Boone, who worked at the OshKosh plant for 37 years. "People used these jobs to buy new houses or new cars and to send their children to school." Afterward, she says, "they had to root hog or die." In other words, they had to scrabble for survival.

Places such as Celina helped carry Mr. Trump to the White House. During the Republican primary, voters in Clay County gave Mr. Trump his best result in Tennessee. In the general election, he received 73 per cent of the vote. Where Mr. Trump was blunt in opposing trade deals, Democrat Hillary Clinton was more muted. Voters here also have not forgotten her husband's role in spearheading NAFTA.

Now Mr. Trump must turn words into action. On May 18, the U.S. government informed Canada and Mexico that it intends to revisit the deal, with talks set to start after 90 days. Early signs indicate that the Trump administration will seek only minor changes to the agreement. Among them: strengthening the deal's enforcement mechanisms and negotiating new provisions governing the digital economy.

The residents of Clay County will be watching to see if Mr. Trump's policies match his rhetoric. While many here hope he will make jobs return, they also acknowledge that what was lost in places such as Celina may never come back. And underneath that current of resignation is something bleaker: a sense that the local labour market has changed in damaging ways.

Older residents complain about an erosion of the area's work ethic. Younger people have grown dependent on government benefits, they say. Like other parts of the U.S., the spread of opioid addiction has also made it difficult for some would-be workers to pass the drug tests required by employers.

Celina's experience reflects new research showing that the impact of trade-related job losses in the U.S. has been deeper than previously believed. Successive trade agreements, followed by China's entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, combined with continued technological change, ushered in dramatic changes for certain industries. In hard-hit areas, researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found a broad increase in unemployment and a decrease in wages, a trade shock that lasted at least a decade.

For the apparel industry, in particular, NAFTA was a turning point. In 1990, the sector employed almost a million Americans. Thirteen years later, 69 per cent of those jobs were gone. Between 1990 and 2003, the apparel industry saw the most jobs destroyed of any broad category of U.S. manufacturing, according to a report from the U.S. Labor Department that analyzed a list of 21 sectors that included the automotive and steel industries.

The apparel industry had begun to unravel before NAFTA, due to increasing competition from imported goods from the Caribbean and elsewhere. But the trade deal accelerated the process, said Timothy Minchin, a historian and the author of Empty Mills, a study of the decline of the U.S. textile and apparel industry. NAFTA is "sort of like the finishing blow," he says. The agreement also had "a visibility that some of the other causes didn't have."

In Celina, with few exceptions, people rarely dwell on the precise causes of the industry's demise. But they know what they experienced, and for them, NAFTA is the line that demarcates what their town was from what it has become.

The ghost tour

For rural places like Clay County, the road ahead is daunting. "The idea that somehow we're in a time warp, and 20 years later we can bring back the same kind of factories that left – it's not the way these supply chains work," says Gary Gereffi, a sociologist at Duke University and director of a research centre focusing on globalization and governance. To bring back jobs, he says, communities have to "recreate some kind of competitive advantage."

Back when OshKosh started out manufacturing work pants and jackets here, Celina's competitive advantage was cheap labour and a plentiful water supply. The company shifted into children`s clothing in the 1980s after its pint-sized striped overalls became a bestseller.

In 1996, OshKosh shut down its main operation in Celina and several other plants in the area, shifting production to Mexico and Honduras. The following year, unemployment in Clay County jumped to 28 per cent, up from 7 per cent when NAFTA took effect.

Some of the company's younger employees found other work, or moved away. But for those with decades of experience on a sewing machine or with a cutting knife, "they go home, raise a garden, do what they can and apply for food stamps," says Mr. Masters, the former OshKosh executive.

Mr. Masters, who retired in 2002 after 40 years with the company, says that several factors contributed to its exit from Tennessee, including rising workers' compensation claims and increasingly stringent environmental regulations. A few years after he retired, the plants in Mexico and Honduras were shuttered when OshKosh moved production yet again, this time to Asia.

Mr. Trump at various points has suggested imposing high tariffs on companies that move jobs out of the U.S. Mr. Masters doesn't like that idea – "Whoever consumes the confounded product is going to pay the tariff, even us hillbillies know that," he says with a laugh.

But he is frustrated by the lack of concerted effort to find and support an industry that could serve as a replacement for the apparel jobs in the Celina area. "If you give up a low-skilled job, what are you going to actively replace it with?" he asks.

Joel Coe, who runs the last holdout from the apparel industry in the area, is pursuing a different solution. His company, Racoe Inc., survives thanks to a provision in U.S. law that obliges military uniforms to be made domestically. He has written to Mr. Trump and his local member of Congress asking them to expand such measures. "The thing that drives me nuts is that all of our Homeland Security uniforms are being made in Mexico," he says.

When Mr. Coe gives a tour of the county, he goes from town to town pointing out ghosts. He can list the names, locations and number of former employees of every closed apparel factory in the region. In the early 1990s, an order for 200,000 pairs of blue jeans was not unusual for his firm. Now he struggles to find customers.

Mr. Trump has not written Mr. Coe back. And while he hopes the President will undertake a radical renegotiation of NAFTA, he is not optimistic. "It would be great if he would. But he won't," says Mr. Coe. Too many donors to the Republican Party have "their finger in the pie for stuff comin' in from overseas."

Like rolling a boulder up a hill

In Celina, finding people who once worked for OshKosh and other local apparel makers is simply a matter of asking the question. Mayor Willie Kerr, who is 79, worked at OshKosh for 32 years. His wife also had a job there.

Down a winding road from City Hall, I visit the executive offices for Clay County – population 8,000 – hoping to speak with the county mayor, Dale Reagan. When I arrive, his assistant, Lisa Thompson, is chatting with Ms. Wix, the director of the seniors centre. Both are former OshKosh employees.

It reminds me of a phrase used by Kevin Donaldson, the head of the Clay County Chamber of Commerce. OshKosh "was our safety net," he says. There was always a job to be had there or at another of the "shirt" factories in the area, as they were known. "Now, if you're not in health care or a teacher, it's pretty slim pickings," Mr. Donaldson says.

Mr. Donaldson and local officials say they have one main objective: turning Clay County into a place where young people can stay rather than leave. Many days, that process feels like rolling a boulder uphill.

Prof. Gereffi, the Duke sociologist, notes that even if Mr. Trump were to somehow bring apparel makers back, the industry itself has fundamentally changed in the interim in ways that favour places that can deliver a specific set of skills. Those tend to be larger towns and cities with an array of educational institutions and resources to lure employers.

There have been small victories. Electronic-parts supplier V&F Transformer Corp., an Illinois-based firm, opened a plant in Celina in 2012. It has grown from five employees to 37 and expects to add another 50 jobs over the next five years. And a homegrown builder, Honest Abe Log Homes, founded in 1979 and based in nearby Moss, continues to expand.

But the community still struggles to fill the hole the apparel industry left behind. Last year, Clay County schools almost shut down after administrators said the cash-strapped district was struggling to pay for health insurance for its employees. At the end of last year, the unemployment rate in the county was 7.2 per cent, nearly three percentage points higher than the national figure.

Like many others here, Dale Reagan, the mayor of Clay County, is hoping that Mr. Trump will help the area to replace at least some of the jobs lost to trade. "That's our prayer," says Mr. Reagan. "I've always heard, 'This country needs to be run by a businessman.' Well, we've got a businessman. Let's see."

A short walk from Mr. Reagan's office, down the hill from the main square, sits the large, low white building that was once the hub of economic activity for the area. The old OshKosh factory is now partially used by Racoe, Mr. Coe's company. The double doors open to a hallway that leads past a darkened office.

There is an area with a few rows of sewing machines, separated from the rest of the vast space by plastic sheeting. A lone employee, Susie Smith, sits near the back, working on a piece of embroidery during her lunch break. Then she begins to cut strips of black fabric for dog vests, part of a small contract with a local seller of pet accessories – a rare non-military piece of business.

Ms. Smith, 55, has an easy laugh and a sad smile. "I'd like to see this county booming again like it did," she says over the whoosh and whine of the cutting machine. "It probably won't happen in my lifetime."

She says she makes less now than she did in 1996, when her old employer – Clay Sportswear, another local manufacturer – shut down and moved overseas. What does she think of Mr. Trump's promise to take a run at NAFTA? "It'd be nice if he did," she says. "Someone needs to take a hold and make a big change. Give him a chance, he will."

Joanna Slater is U.S. correspondent for The Globe and Mail

On June 7 in Toronto, The Globe and Mail is holding a live panel discussion, Globe Talks: NAFTA in Play, on the future of trade with our biggest partner, featuring Globe journalists Barrie McKenna and Joanna Slater with experts Dan Ciuriak, Laura Dawson and Michael Kergin. For details and tickets, visit tgam.ca/NAFTA

Follow The Globe's ongoing coverage of trade issues and track of the renegotiation of the North American free-trade agreement. tgam.ca/trade

MORE ON NAFTA