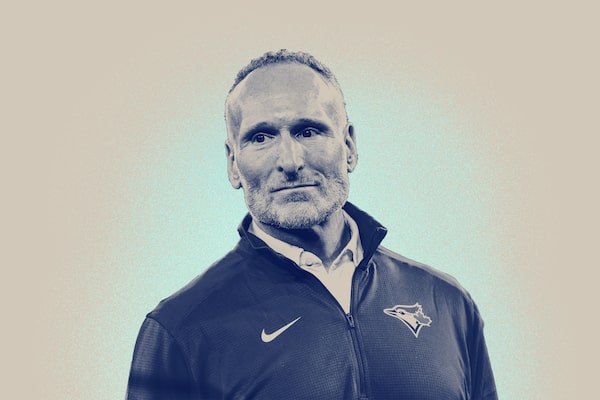

Photo illustration: The Globe and Mail. Source photo: Cole Burston/The Canadian Press/The Canadian Press

“It is not the critic who counts” begins a famous Teddy Roosevelt quote, which hangs in Mark Shapiro’s office at the Rogers Centre. That advice probably comes in handy for a man like him – appointed general manager of the Cleveland baseball team at the age of 34, supporting figure in the book and film Moneyball, now in his eighth year as president and CEO of the Toronto Blue Jays – who might otherwise be distracted by off-the-field drama. In the past couple of months alone, Shapiro has had to oversee the Jays’ response to a (now former) pitcher‘s problematic social-media posts (complaints about in-flight service and popcorn cleanup; transphobia) and then try to soothe long-time season-ticket members who are distraught over their imminent renoviction from seats they’ve held for decades, as the club gets set to build luxury facilities to cater to more VIPs. Still, though he doesn’t like talking about himself, Shapiro recently agreed to an afternoon chat on the Corona Rooftop Patio – one of the festive new bar areas that opened this year – as staff prepared the stadium for a game that night.

Why is that Roosevelt quote important to you?

We live in a world where people are so comfortable judging and criticizing what other people are doing. As I go through life, now at 56 years old, the only thing I’m certain of is that I’m certain of nothing. And that I’m less sure of everything today than I was yesterday.

On what occasions do you lie?

Hopefully never. There’s times in these jobs when your communication – I guess it would be considered spin instead of lying. An example of that would be explaining why you make a player move. You don’t have the ability to explain a player’s health or maybe the dynamic behind the scenes in a locker room. You can’t slander a player, you can’t invade their privacy. So, sometimes it’s challenging to communicate the reasons for everything that’s done, to a public and a fan base that cares deeply. The decisions you make won’t always be understood, and you have to accept that in these jobs.

There are times that you’re explaining things and you can do it very adeptly and intellectually and have strong rationale. But I don’t work in a business that is rooted in rationale and intellect, I work in a business that – you know, our fans, the mere definition of the word ‘fandom’ means there’s emotion.

Right. They’re ‘fanatical!’

They’re fanatical and emotional. And people don’t want to rationalize sport – and that’s okay, I embrace that, I accept that, we need that.

That’s what fills the stands – well, that and bobblehead giveaways.

And hot dogs! Dollar hot dogs!

What trait do you most deplore in yourself?

Probably a lack of patience.

How does that manifest?

It manifests in the things I’m least probably proud of myself. I sometimes cut people off, I sometimes start multitasking while I’m talking to someone. I sometimes lose attention span. I think my desire to drive and continue to kind of push things through sometimes is just at a pace that’s not fair to people around me – that either work with me or live with me. And that can be a challenge.

What trait do you most deplore in others?

Lack of humility. I wish I was more tolerant of it. But when I see someone who lacks humility, I am so turned off by that. Because I just think, if you’re not humble, then you’re not open-minded. If you’re not open-minded, you’re not curious and learning. And if you’re not curious, learning, humble and open-minded, you’re not improving, growing, getting better. And the people I choose to spend my life around – when I have choice – are people that are rooted in those things.

What’s your greatest extravagance?

I’ve flown private once or twice with my dog [an adorable golden-doodle name Cleoh], just because I didn’t want to put him underneath and couldn’t drive him to Florida when we had to work down there, during COVID. I think that’s probably the most extravagant thing I’ve ever done. And the thing I’m most embarrassed of.

Embarrassed? Why?

It’s not anything I ever dreamed I’d be able to do. And I know 99.9 per cent of the world could never do that.

Did he spill popcorn? And then did you …

Tweet it out? Haha. Yeah. He’s incredibly well behaved, even on flights.

What words or phrases do you overuse?

I think if you were my kids, you’d probably be tired of hearing, ‘Control the controllable.’ [His son, Caden, is 20; his daughter, Sierra, is 18.] We tend as a species to fixate on the small percentage of things that we can’t control: What other people think, what other people do, forces of nature. And yet, if we just broke our day down, the 24-hour period, and thought about the hundreds of things we can control, starting with the interactions we have with the people that matter most of us, to what we eat, to how we sleep, to how we exercise – all those things that are controllable – you start to feel a huge sense of empowerment.

Do you have a favourite character in fiction?

I always go back to Howard Roark and Fountainhead. That was a seminal moment for me in my early 20s when I read that.

Oh? Why?

As much as objectivism is not a philosophy to live your life by, and Ayn Rand was clearly a flawed human, at that moment in time, thinking about, like: Okay, I’m the byproduct of these incredible institutions – my dad, my family, my high school, my university – trying to peel away the impact of those people, to figure out what is inherently me. And understanding that so many people around me, particularly at Princeton, were so consumed with the race to measure themselves against other people by money, power and fame. I had to reach that point where I was, like: Okay, those things are going to give me no fulfilment. So what are the things that will, and what is inherently me?

A lot of people read Rand and become selfish.

Yeah. No, I think a sense of self is extremely important, even as depicted and described in Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead, but if you don’t live a life of connectivity and caring, it’s going to be an empty life.

Do you have a favourite sports movie?

[His eyes grow wide.]

It’s not Moneyball. [Pause] Field of Dreams. It’s like a religious experience for me.

Did you used to have a catch with your dad?

I had many catches with my dad, and I played whiffle ball and stick ball and I hung over the fences at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore as a kid. And there are seminal moments of my childhood that were around the game of baseball. My dad grew up in inner-city Philadelphia and just loved the game. I think, as a son of an immigrant, maybe that was the most American thing that he could grasp.

You mentioned Moneyball. On a scale of 1 to 10, how true is the film?

Uh, three? The sections with me are zero.

Because you’re more handsome than the actor Reed Diamond, is what you’re saying.

Listen, man, I met and talked to Michael Lewis. He was a few years ahead of me at Princeton. I had read Liar’s Poker and The New New Thing and thought they were incredible. I think when I read Moneyball, I was like: Okay, now I get it, he’s an incredible writer, he’s a storyteller, but he’s exaggerating everything around the main character, because he has a main character. And then when the movie came out and it said, ‘Based upon a true story,’ it kind of ruined every other movie that says that, because I was, like, how loosely based?

I once heard an interview with Michael Oher, who’s the subject of The Blind Side (Lewis’s 2006 book, which was adapted into a 2009 film). He had written a book about himself and they asked, like, ‘Why did you write a book, there’s already been a book?’ and he said, ‘Because the book was fiction and the movie’s fantasy.’

Simon Houpt

Simon Houpt