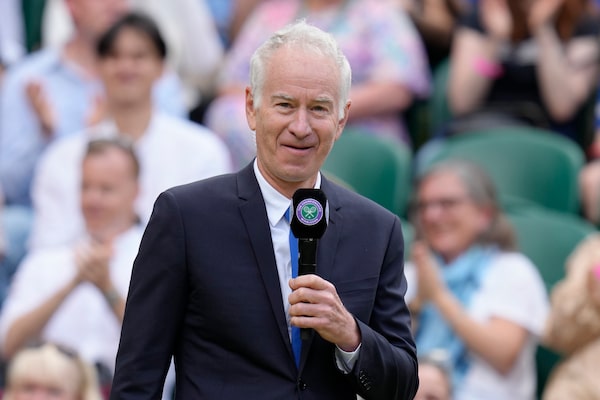

Former tennis player John McEnroe speaks during a 100 years of Centre Court celebration on day seven of the Wimbledon tennis championships in London on July 3.Kirsty Wigglesworth/The Associated Press

Ahead of Novak Djokovic’s second-round match against Australia’s Thanasi Kokkanakis, John McEnroe got on one of his favourite topics – the world, and how little sense it makes.

McEnroe was sharing the BBC booth with former Australian pro Todd Woodbridge, a genial, hail-fellow-well-met type.

Woodbridge wanted to talk about tennis. McEnroe wanted to talk about Australia. He is still upset with the way the country treated Djokovic at this year’s Australian Open – letting him in and then kicking him out over vaccine compliance.

“I don’t understand!” McEnroe – who speaks in question and exclamation marks, but few periods – yelled. “It doesn’t make any sense!”

“Yes, well, very unfortunate …,” Woodbridge mumbled, trying to hurry things along.

“It’s crazy!” McEnroe said, sounding more delighted than enraged.

“Hm-hm,” Woodbridge says, trying to speak noncommittally in a language other than English.

“Explain it to me!” McEnroe said, voice rising.

“I thought I was just here to call a tennis match,” Woodbridge said meekly. At that point, McEnroe took his teeth out of Woodbridge’s leg and let him scamper back to the safety of the keys to victory.

That’s the difference between McEnroe and every other high-profile TV analyst everywhere. They are there to call a sports contest. He’s there to talk about the world as he sees it, with a little sports thrown in.

Every year at Wimbledon, you are newly reminded of the allure of this tournament. There’s the tennis, the official beginning of summer (school-days edition) and the beauty of the place.

But for me, it’s this place at this time of year with McEnroe in charge. This magical combination reaches back to the early eighties in what only seems like an unbroken string.

When you reach a certain point, you realize there is an ideal voiceover to your life. Preferably, someone who’s been along with you for the whole ride. For me, that’s McEnroe. Whenever the big questions come up, I hear them in that reedy, irritated, outer boroughs twang of his.

Now 63, he is close to becoming Britain’s defining figure for these two weeks of each year.

Over the past week, he got in trouble (again) for swinging on behalf of Djokovic’s right to be stupid. He headlined the tabs after sending best wishes to jailed colleague Boris Becker: “We miss you, man!” He did so again when he refused to apologize for maligning Emma Raducanu’s exit from the tournament last year.

He scandalized the nation when he referenced retiring BBC colleague Sue Barker’s decades-old relationship with saccharine pop star Cliff Richard. Then, a moment later, he reduced Barker to tears when he went off-script, asking the crowd to salute her.

His pronouncements routinely lead headlines here. The Guardian has a “John McEnroe” tab on its sports pages.

During the celebrations for the centenary of Centre Court, he was both the emcee and the only non-Brit given a speaking role. Without the bother of an audition, McEnroe has become the de facto voice of Wimbledon. What else do you call it if you’re the one hosting the birthday party?

This late-career isn’t the result of polish and aspiration, but of its opposite. McEnroe fell sideways into broadcasting. At first, he was considered a sideshow, someone more than a little out there.

As the years passed, McEnroe stayed the same, but the ground shifted around him. No one would call him a rabble-rouser now. In a sports media world populated by screamers and sycophants, he still sounds like he’s saying what he actually means.

That what he says about tennis is often discussed more than the tennis itself is a nice bonus. That it often ties him in logical knots even moreso.

Take his harping about Nick Kyrgios, who advanced to the quarter-finals on Monday.

During Saturday’s instantly infamous Kyrgios-Stefanos Tsitsipas match, McEnroe went in hard on the Australian. He referred to his ability to get away with things as “insane.”

To recap: John McEnroe, a man who once shattered a bunch of water glasses with his racquet at a match in Sweden, dousing a row of innocent Swedes, thinks complaining at Wimbledon is “insane.”

I’m not sure anything in the sports context qualifies for inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, but if so, that would be it.

But this sort of amusing hypocrisy is a key to McEnroe’s brilliance as a commentator, in much the same way it was his secret as a player. Yes, he is petulant and contrary and often contradicts himself. But he does it in a way that is so obviously authentic that it is irresistible.

I once asked McEnroe how many of those tantrums during his playing days were a performance.

“None,” he said. “Now, it’s all performance. It’s embarrassing.”

Of course, you were meant to wonder if he was kidding. The self-deprecation – a quality few sports greats can master – blunts the edges either way.

McEnroe is the sort who is convinced he is right, but willing to be proven wrong. He can be cutting, but is never capricious. And unlike a lot of yellers on a lot of topics, he is careful never to wander into the dead-end of misanthropy.

You can tell by watching him that he likes people. If you can figure out that part of life, you are already halfway to success.

Even people who don’t like Boris Becker or Novak Djokovic will admit they’d like a friend like John McEnroe. So while he is often ripped online, one suspects he is quietly beloved everywhere else. This is what happens to any famous non-conformist these days.

Seeing him around Wimbledon this past week, he has lost none of his bounce. Wherever he goes, the action is happening. If it isn’t, he makes it happen.

There is no other announcer/analyst like him anywhere. If tennis is one of the only global games, McEnroe is the only true global announcer. He is known everywhere and, like Shakespeare, his takes translate into every language.

In the fullness of time, we may think of him as the great sportsman of his era – not as a player or a broadcaster, but as someone who defined a way of thinking about how we approached our games across a span of decades.

Cathal Kelly

Cathal Kelly