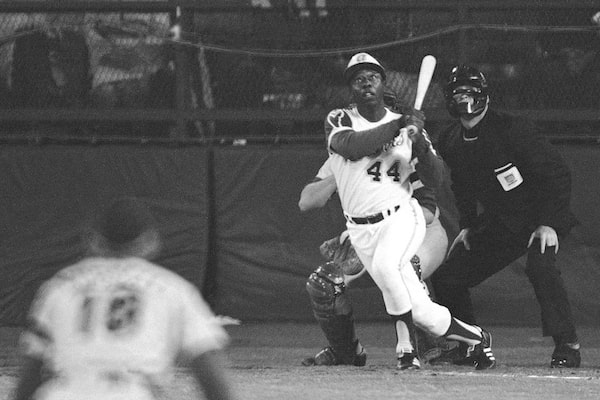

Atlanta Braves' Hank Aaron eyes the flight of the ball after hitting his 715th career homer in a game against the Los Angeles Dodgers in Atlanta on April 8, 1974.The Associated Press

In the first of what would become a volume’s worth of hagiographical profiles written about him in Sports Illustrated, the scene is set with Hank Aaron arriving at spring training. It was 1956. Mr. Aaron was 22.

Mr. Aaron sauntered – the magazine’s word, not mine – up to the plate. He’d borrowed a bat from a teammate. He took no practice cuts. He stepped in and knocked the first three pitches out of the park.

Then he turned to no one in particular and said, “Ol’ Hank is ready.”

No ballplayer in history was more ready for his moment than Henry Louis (Hank) Aaron. He didn’t just singlehandedly pulp the record books. He wasn’t just the best right-handed hitter in baseball history.

What made Mr. Aaron special was that he did those things while a good chunk of the paying public rooted against him, many in the ugliest terms imaginable. He turned the simple act of showing up for work each day into a heroic gesture.

Mr. Aaron’s family announced on Friday that he’d died. No cause of death was released. He was 86.

Just two weeks ago, reporters were on hand as he got the coronavirus vaccine. It was Mr. Aaron’s hope that seeing him get the shot would encourage other Black Americans to do likewise.

“I feel quite proud of myself for doing something like this,” Mr. Aaron told the Associated Press. “It’s just a small thing that can help zillions of people in this country.”

For the majority of his major-league career, the most remarkable thing about Mr. Aaron was how a player this good could be so unremarkable.

He wasn’t a preener or a showboat. He wasn’t a big, imposing man, or especially fast. When people talked about his superpower, it was his wrists. He had unusually large wrists, allowing him to throw the bat forward like a spinning airplane propeller.

Like many others in his generation, Mr. Aaron came up poor in the Deep South. He taught himself to hit cross-handed – left hand over right. Because he couldn’t afford a bat or a ball, he honed his ability hitting bottle caps with whittled-down sticks.

Mr. Aaron began his pro career as a teenager in the Negro Leagues, five years after Jackie Robinson had broken Major League Baseball’s colour barrier.

He would later recall a team meal at a diner in Washington. After they’d finished, the waitstaff took their plates into the back and shattered them.

Atlanta Braves employees place flowers next to a portrait of Mr. Aaron outside Truist Park, in Atlanta on Jan. 22, 2021.John Bazemore/The Associated Press

“If dogs had eaten off those plates, they’d have washed them,” Mr. Aaron said.

After a year, he signed with the Milwaukee (later Atlanta) Braves.

Mr. Aaron was not a name-up-in-neon performer. He didn’t put up circus numbers. His calling card was consistency. He had no good years or bad years. He had Hank Aaron-type years, every year.

How consistent was he? Mr. Aaron got most-valuable-player votes in 19 consecutive seasons.

How underrated was he? Despite setting the all-time career marks in runs batted in, extra-base hits and total bases, he was only named MVP once.

Because the Braves weren’t nearly as great as he was, Mr. Aaron didn’t bob to the surface of the American imagination until he was 37 years old. That’s when he began closing in on Babe Ruth’s all-time home-run record.

Mr. Aaron hit his 600th homer in April, 1971. He wouldn’t pass the Babe’s mark – 714 – for nearly three seasons.

During that time, Mr. Aaron became the most famous, the most discussed and the most resented athlete in America.

The racial abuse he faced was medieval. He had to hire an assistant to sort his correspondence – a few fan notes and a great mountain of hate mail.

The bile of his often anonymous persecutors was so overflowing, they started sending death threats to his assistant as well, because she was Jewish.

Some of the threats were so detailed the FBI advised Mr. Aaron to hire a bodyguard. For security reasons, he couldn’t stay in the same hotels as his teammates. He spent some nights bunking alone in empty ballparks. His children required their own protective details.

Mr. Aaron never showed much interest in Mr. Ruth’s record while he was reeling it in, but he refused to be cowed for going to work every night.

“It wasn’t just playing against Babe Ruth,” teammate Dusty Baker said later. “He was playing against parts of America.”

He hit his 713th homer on the second-to-last day of the 1973 season. That extended the chase another six excruciating months. During that time, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution wrote his obituary, just in case.

Mr. Aaron broke the record on April 8, 1974 – the fourth game of the season. He drove the second pitch of an at-bat just over the left-field fence into the bullpen.

The man who surrendered the hit, Los Angeles Dodgers starter Al Downing, had a long and laurelled career. But in that moment, Mr. Downing realized he’d become the answer to an obscure piece of bar trivia.

“If you don’t want to give up home runs,” Mr. Downing shrugged. “Don’t pitch.”

Most baseball fans can recall from memory Mr. Aaron’s loping run around the bases. His parents met him at the plate. Only once he’d laid his eyes on them did he seem excited.

Les Motes and his two-year-old daughter Mahalia leave flowers near the spot where a ball hit for a home run by Mr. Aaron, clearing the wall to break Babe Ruth's career home run record in 1974.John Bazemore/The Associated Press

Interviewed a short while later, Mr. Aaron appeared to take little joy in his achievement. The best he could come up with was, “Thank God, it’s over.”

Mr. Aaron played two more years, but his career effectively ended that night. He’d dragged baseball – some of it unwillingly – from one era into the next.

In retirement, Mr. Aaron became one of the game’s wise men. A consensus became to form around him – that he was the professional’s idea of how a professional ballplayer ought to comport himself.

He worked for years in the front office of the Atlanta Braves. He lent his name to charitable causes, especially those involving children. He owned an eponymous string of car dealerships.

Eventually, Barry Bonds – aided by more than bottle-cap practice – overtook Mr. Aaron’s career home-run mark of 755. This was in the teeth of the steroid era. Everyone knew what was going on, but no one could figure out what to do about it.

Mr. Aaron wasn’t there the night Mr. Bonds broke his record, but he did pre-tape a video tribute.

Mr. Aaron – a man who’d built his legend on the simple rule of showing up and doing a day’s work for a day’s pay – never bad-mouthed Mr. Bonds. He also never made much of a secret of what he thought of his approach to the game.

Long after he’d finished playing, Mr. Aaron kept the hate mail he’d received during the pursuit of Mr. Ruth’s mark. He would show it to startled friends, and occasionally sit with it alone in his attic.

“We have moved in the right direction, and there have been improvements, but we still have a long ways to go in this country,” Mr. Aaron told an interviewer in 2014. “The bigger difference is that back then they had hoods. Now they have neckties and starched shirts.”

Cathal Kelly

Cathal Kelly