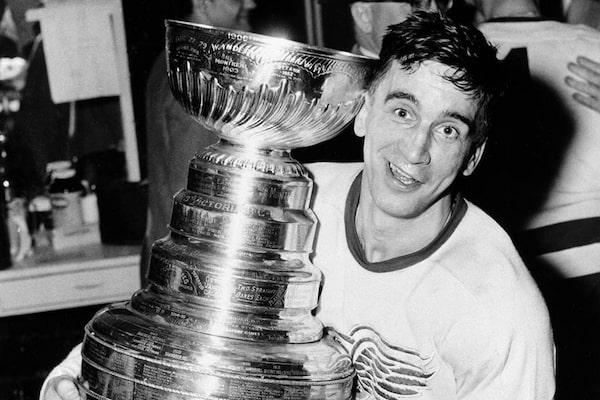

Detroit Red Wings captain Ted Lindsay hugs the Stanley Cup after his team defeated the Montreal Canadiens, 4-3, in a sudden-death extra period to win the final in Detroit on April 16, 1954.The Associated Press

Of all his wars, on and off the ice, Ted Lindsay’s most notorious was probably a vicious 1951 brawl with Boston Bruin Bill Ezinicki.

There was history between the pair stretching back to junior hockey. This set-to started out with shoving. It elevated to stick swinging. Very quickly, it turned into a sword fight. By some estimates, the battle lasted an astounding four minutes, with the pair battering each other while dragging desperate referees around the rink.

Eventually, Ezinicki was knocked unconscious. At which point, Lindsay got down on top of him and continued punching.

Recounting the fight 60 years later, Lindsay told the Detroit Free Press that it was Gordie Howe who tried to calm matters.

“Gordie says, ‘Ted, he’s out.’ I said, ‘I’m going to kill the SOB.’ ”

Later, Lindsay popped by the medic’s room – Ezinicki had a broken nose and required two-dozen stitches to close up multiple wounds – stuck his head in and yelled, “You alright, Izzy?”

That was Lindsay all over – brutal, but still gracious. Like so many of his colleagues, Lindsay wasn’t just of another time, but another culture.

One of the last surviving tethers to that generation, Lindsay died on Monday at the age of 93.

His hockey renown rests on his work for the Detroit Red Wings’ “Production Line,” along with Howe and Sid Abel. He won four Stanley Cups in Detroit and once led the league in scoring.

But it was Lindsay’s pugnaciousness that made him legendary.

He wasn’t a big man – five-foot-eight, a buck-sixty-five – but he lacked fear. Lindsay is widely credited with prompting the NHL to create one frequently called penalty (elbowing) and one less so (kneeing). He was also infamous for working the normally placid Howe into fits of rage on the bench, ones that Howe would then take out on Detroit’s opponents.

“I hated everyone I played against,” Lindsay said decades later. “They were the enemy, and we were supposed to win. Not them.”

If thuggish while in uniform, Lindsay was no blunt instrument out of it. His wide streak of us-vs.-them-ism contained enough room for a rough sense of justice. He was among the first to speak out about ownership’s monopoly over players’ careers.

At the time, most NHLers took jobs during the off-season to cobble together a living wage. There was no league minimum salary, the details of the NHL’s pension plan were kept secret from its beneficiaries and players’ rights were owned in perpetuity by the team that had first acquired them.

Along with several other bold-face names, Lindsay began a secret drive in the mid-50s to found an NHL Players’ Association. The choice of name was important, since no one dared use the word “union.”

When Detroit general manager Jack Adams found out about it, he went through the dressing room asking each of his employees if they were for the union. Only Lindsay looked him in the eye.

Ted Lindsay of the Detroit Red Wings, fights through the block of two Boston Bruins during a game in December, 1949.The Associated Press

For his trouble, Lindsay was stripped of his captaincy, slagged in the press (a false story was planted that he earned more than Howe) and traded to Chicago.

The fight ended up in court. Having seen how Lindsay – a superstar – was treated, player support drained away from the effort. The owners eventually settled, giving in only to the most basic player demands. Lindsay had won and lost at the same time.

The players’ union wouldn’t become a going concern for another decade, but the image of Lindsay as something between the Cesar Chavez and Jimmy Hoffa of the NHL had already taken hold. It would be his most celebrated achievement.

He played on for a few more years. He tried coming out of retirement for a swan song with the Wings, but Toronto Maple Leafs owner Stafford Smythe refused the unanimous league consent required at the time.

Like his father, Smythe had never forgiven Lindsay – an Ontarian - for choosing Detroit over Toronto.

Lindsay was invested into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1966. He refused to attend his own induction because his wife and children were not allowed into the men-only ceremony.

“I have my principles,” Lindsay explained at the time.

The next year, they changed that rule.

Lindsay had a rich life after hockey, one that never strayed far from the site of his greatest triumphs and lowest professional lows.

He did play-by-play for a bit, the sort that would make Don Cherry blanch for its open celebration of violence. He was briefly general manager of the Wings. He was a noted supporter of children’s charities.

As the decades slipped by he did what few athletes manage – transform from a regular hero into a cult one. There was something about the mix: Lindsay’s unflagging aggression, his rise, fall and rise again that agreed with the Motor City’s view of itself.

He was a tough guy in the way people like to imagine the type – a wonderful friend and a horrible enemy.

On the ice, Lindsay wasn’t kind to others, but he was fair. The fairness won out. In the weird way of the world, this professional misanthrope sacrificed more than anyone else to advance his colleagues’ cause.

The Red Wings got good again in the nineties. Lindsay was a fixture around those teams, so much so that they gave him his own locker. Well into his 80s, he’d show up daily for a workout and a natter.

The NHL eventually came around on him. In 2010, the trophy for the league’s most-outstanding player was renamed the Ted Lindsay Award.

At that ceremony, Lindsay held court with reporters for a while. He mentioned that he’d had back surgery a few years before and had finally given up the game for good.

“My doctor says, ‘You can play hockey, but you can’t get hit',” Lindsay said. “And I said, ‘Why play hockey if you can’t get hit?’ ”

Cathal Kelly

Cathal Kelly