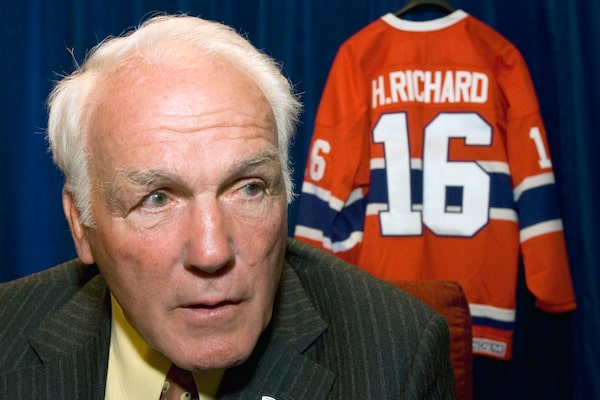

Former Montreal Canadiens' Henri Richard responds to questions in Ottawa, Ontario on June 1, 2007.Paul Chiasson/The Associated Press

Every four years he’d be back in the news – the most recent being last Saturday, when he finally turned 21.

Well, actually, it was Henri Richard’s 84th birthday, but when you’re Canada’s best-known leap-year baby people tend to think of you on Feb. 29. Both numbers – real age, leap-year age – are invariably mentioned.

A week later, Canadians are thinking of him again, many with a touch of sadness, some surely with relief that the Montreal Canadiens’ great, little centre will no longer struggle with Alzheimer’s disease.

There have been a great many other numbers mentioned as well: 20 seasons with the same team, 358 goals, 688 assists, 1,259 regular-season games, 129 points in 180 playoff games, 10 times an all-star, named one of the game’s top 100 players in 2017.

The number that impresses most, however, is 11 Stanley Cups, more than any player in history, more rings, if they had given them out in the early years, than appendages.

“No one’s going to break that record,” he once said. “It’s impossible. I say that without boasting.”

There were also numbers concerned with size that seem equally impossible: 5-foot-7, 160 pounds, the reason behind a nifty nickname, the Pocket Rocket, that he personally despised. But when your older, much larger brother is Maurice (Rocket) Richard – the most fearsome scorer of his day – what else could you expect?

His junior coach told him he was “too small” to think about a career in hockey. He would tell his teachers he’d be a “plumber” or some other tradesman when he grew up. “I never said hockey player,” he says in an old clip that aired on Friday in a Stephen Brunt essay for Sportsnet.

He became such a successful hockey player, however, that for decades he stood as an inspiration to the undersized, the under-anticipated. Gifted small players everywhere could look at him and say, “If he can do it, I can do it.”

His heart, no surprise, was huge. He defined the much-used phrase “fierce competitor.” After a superb junior career, the little centre was invited to the Canadiens’ training camp in the fall of 1955. Some whispered that it was just a favour to the Rocket, 15 years older and long entrenched as the team’s greatest star. Others said he would soon be sent back to junior, as was very much the norm in the days of the Original Six.

The Rocket’s little brother stunned them at that first camp. Red Fisher, the late, great Montreal Gazette columnist, wrote that the head coach, Toe Blake, said that “when Richard was on the ice, nobody else had the puck.

"At the start of training camp we had no idea what we had. At the end, we couldn't send him back.”

They worried that the slick little playmaker might handle the speed and play but could he deal with the rough stuff in an era of bench-clearing brawls, swinging sticks and no helmets. Not only could he handle it, he often initiated it.

Maurice often said that his little brother was a better all-around player. The two would play together, sometimes on the same line, for five years, each year winning the Stanley Cup. The general manager of the day, Frank Selke Sr., told Fisher that even though the team had the Rocket, Jean Béliveau, Doug Harvey and Bernie (Boom Boom) Geoffrion, “game in, game out, Henri Richard may have been the most valuable player I’ve ever had.”

He could be fierce on the ice and off. During a dressing-room discussion about harsh media coverage, some players suggested not letting the press in. Richard defended the reporters, saying they had a job to do. Serge Savard, then a youngster with the team, joked, “If you like them so much, why don’t you sleep with them?” Richard rose from his seat, walked over to the much taller, much larger Savard – and slapped his face.

He was incredibly loyal to the Canadiens and expected loyalty in return. He was a veteran when, coming off an injury, management decided to sit him out another game and let an impressive young Jacques Lemaire take his place in the lineup. Richard left the building without informing anyone and went home. Next day he told reporters he would “rather pick garbage than sit [out]."

In 1971, nearing the end of his career, he was left out of the lineup for a playoff game. He responded by calling head coach Al MacNeil “incompetent.” The team went on to win the Stanley Cup, but next year MacNeil was gone and Richard had his regular spot in the lineup. He captained the team to his final Cup, in 1973, and retired two years later, serving for many years after as a team ambassador.

“He was extremely respectful and kind,” says Ken Dryden, who played goal for the team during Richard’s final years. When Dryden was called up in March, 1971, with the team struggling, Richard welcomed him. “He never treated me as anything other than a teammate. Not the kid. Not the college goalie. I was a player.

“Once you got to know Henri he was funny and had this great laugh. His eyes would just twinkle.”

Dryden remembers being in goal and watching No. 16 skate – “never in a straight line” and seemingly forever. When researching his book The Game, Dryden took a stopwatch and measured old games to see how length of shifts had changed over the years. In the 1950s, players stayed on for two minutes or so. Not Richard. “Routinely 3:20, 3:30,” Dryden says. “He was the only one. He never quit.”

After Dryden’s arrival that March of 71, the team began winning. They made the playoffs and went to the Stanley Cup final against the Chicago Blackhawks. In the seventh game, the Canadiens were down 2-1 when, stunningly, Henri Richard took over.

“By then Henri was 35 years old and pretty much a non-scorer,” Dryden recalls. “He had a truly horrible shot. I knew it. Bur then he scores the tying goal and the winning goal.

“It wasn’t the power of his shot. He simply willed those goals in.”

Roy MacGregor

Roy MacGregor