Over the past couple of months, as Toronto sports fans rejoiced over a rare pair of championships, I found myself thinking wistfully of the weekend that my teenaged son and I spent watching terrorists try to blow up a Russian train yard.

This was a little over a year ago, when I still harboured faint hopes of Sascha inheriting my love of traditional pro sports. At his age, my life was a blur of backyards and ball fields and neighbourhood rinks. He, meanwhile, was spending most of his free time in the dark, banging away on a turbocharged laptop, playing Counter-Strike: Global Offensive – an online video game that is basically a series of military firefights.

Mind you, he wasn't just playing. Unlike the arcade games of my own teen years – the seductive Galaga and its battalions of aliens descending in formation bled my paper-route savings dry, 25 cents at a time – online games are as much watched by spectators on the internet as they are played. Charismatic gamers become celebrities, broadcasting their play for hours each day on sites such as Twitch, a streaming service, which Amazon bought for almost $1-billion in 2014. Dozens of other sites offer livestreams of professional-level games being played around the world.

For months, Sascha had been emerging regularly from his basement lair to ask if he could share some highlights of a CS:GO game that had just come to a thrilling conclusion.

I submitted on occasion, but with flecks of resentment that I wished I could hide better. I had been born weeks before the Leafs won their last Stanley Cup and had grown up at the knee of a brother five years my senior who by day stuck me in front of our garage door and took endless slap shots with muddy Slazenger tennis balls and by night instructed me in the whispered catechisms of Sittler and Henderson and Keon and Hammarstrom. Grey Cups were family affairs.

At age 12, when I misjudged a high pop-fly during a competitive backyard game of catch and the errant ball smashed my nose, it was a vintage Toronto Blue Jays T-shirt that absorbed the bloody gush.

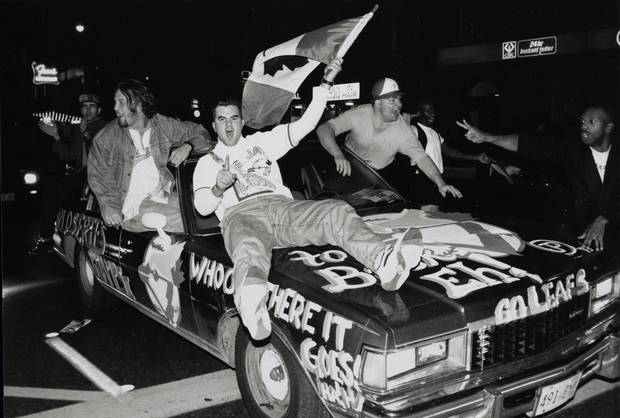

Years later, on a glorious late-October night, my not-yet-wife and I joined hundreds of thousands of other Blue Jays fans parading up and down Yonge Street after Joe Carter hit his legendary blast over the SkyDome's left-field wall. But as we became parents, other activities nudged pro sports aside, even if Maple Leafs and Blue Jays games still played mutely in the background of our growing family chaos. Our two girls' competitive spirit found an outlet in dance. And though Sascha was playing shinny in the living room of our apartment at age 2, his interest waned as the Leafs spent years wandering in the desert. He was 11 when the Leafs endured their Game 7 implosion against Boston in 2013; I don't think he looked at hockey the same ever again.

Celebrations on Toronto’s Yonge Street after the Blue Jays won the 1993 World Series.

File Photo

Still, his enthusiasm for watching video games over pro sports made me feel guilty, as though my wife and I had failed as parents to grant our children their (blessed, cursed) birthright as Torontonians. I struggled as his screen time expanded, feeling as though he was preparing himself for a career as a drone pilot. Besides, the action in

CS:GO unfolds in a whiplash frenzy. Trying to make sense of it made me feel incompetent. (Which is to say, old.)

But I also knew that so-called e-sports were going mainstream: that some former pro athletes such as Shaq and A-Rod were investing in teams, that marketers and mainstream broadcasters were rushing into the scene, that U.S. colleges were offering scholarships for promising e-sports players, that the 2024 Paris Olympic Committee is mulling the inclusion of some e-sports games and that the Air Canada Centre had just been full for two days with fans cheering on their teams in the North American finals of a League of Legends tournament.

So when Sascha decided that – for his 15th birthday at the end of the summer of 2016 – he wanted to spend the weekend at Fan Expo, the annual bacchanal of sci-fi, cosplay and celebrity culture at the Metro Toronto Convention Centre, which would play host to a professional e-sports tournament known as Northern Arena, I asked if I might tag along. His eyes lit up.

At the far end of the south building, I stepped through a door and found myself in a pop-up sports coliseum. It was a tiny set-up compared to other tournaments I'd seen online, with stadium-style seating for only a couple of hundred fans ringing three sides of the room. But it had the genre's familiar trappings: Miami nightclub lighting, thudding music during the breaks in play, cameras swooping up and down on cranes. (Like all e-sports tournaments, this one was streaming live online.)

In pro sports, teams meet each other head-to-head. Here, the teams sat on either side of the room, facing away from each other, toward their computers. Between them was a sort of dance floor, upon which were projected live images of the games as they unfolded. A broadcaster's booth was on the far side of the floor, where a trio of colour commentators known as "casters" offered running analysis; I had no idea what they were saying, but Sascha nodded along to their insight. And their voices played like a rough symphony, cuing me to the ebb and flow of the game.

Counter-Strike: Global Offensive is a first-person shooter game in which one team of five players spends 15 rounds, each about two minutes long, in the guise of terrorists, trying to plant a bomb at one of two locations on a map.

The other team represents counter-terrorists who try to prevent the bomb from being planted – either by killing all of the terrorists or protecting the prospective bomb sites and running out the clock – or defusing it before time runs out. (Players move around the map by pressing the W-A-S-D keys, jump with their space bar and shoot with their mouse.) After 15 rounds, the teams swap roles: terrorists become counter-terrorists and vice versa. The first team that wins 16 rounds wins the game; two games earn the match.

If it seemed simple at first, I began to grasp the levels of strategy underlying the bloody mayhem on-screen. (It's actually not nearly as bloody as other games I'd seen: Here's looking at you,

Call of Duty.) Players need to consider issues of economy and scarcity. They each begin the game with a pistol and an equal amount of cash, with which they can buy a weapon or armour. If they die, they lose the weapon (a lucky opposing player might pick it up), but if they survive, they can carry it into the next round. At the beginning of each new round, they get more cash (the amount varies, depending on whether they won the previous round) to buy more weapons or armour.

The action takes place in a gritty urban landscape chosen from a handful of options by one of the teams at the beginning of the game (a German overpass; a Chernobyl warehouse; a Russian train yard, etc.), each of which has well-chronicled advantages and disadvantages for the two sides.

Richardo “boltz” Prass, left, and Henrique “hen1” Teles, right, of Team Immortals from Brazil, battle Team Cloud9.

Glenn Lowson/The Globe and Mail

At Northern Arena, a large screen above the caster's desk showed an aerial view of the action, with each player represented by a dot. On another screen, the image flipped rapidly among the first-person, ground-level view of each player.

Next to me, Sascha described the various attack and counter-attack strategies unfolding on the screen and began to tell me about the players on the floor, some of whom he'd been watching online for years. A local news crew overheard his analysis and asked if he would explain to their camera what was going on in the game. (Mainstream media outlets don't yet have e-sports specialists.) He cheered for his favourite team, Cloud9, but he warned me it had a tendency to collapse in the final rounds of matches.

Cloud9 is based in the United States, but one of its star players was a guy in his early 20s from Toronto named Michael Grzesiek, who goes by the name "shroud" and wears a tiny Canadian flag patch on his jersey. There aren't many like him. Carl-Edwin Michel, a tech-journalist-turned-entrepreneur and CEO of the Canadian League of Gamers, which produced Northern Arena, told me he was hoping to help change that. "I wanted to do Northern Arena because there's no real platform for Canadian players and organizations to be in the top tier here."

That's partly because of a lack of infrastructure. As online creations, teams depend primarily on sponsorship and Canadian marketers have lagged behind their international counterparts. (In the fall, Labatt Breweries of Canada announced its first e-sports initiative.)

That means Canadian players face hurdles in professionalizing their play. Similar to teams in legacy pro sports, well-financed e-sports players have access to trainers, nutritionists, psychologists and other experts to pump them up to peak performance. The players embody the dedication and rigour of Olympians, living together in team housing, training eight to 12 hours a day (at the gym as well as the computer) and monitoring their diets with almost scientific precision.

Still, there is widespread skepticism among non-fans: A few days before Northern Arena, Ontario politician Tim Hudak posted an admiring note on Facebook about the recent League of Legends event at the Air Canada Centre, suggesting that e-sports was "probably the biggest thing you've never heard of." To which a sputtering Andrew Coyne tweeted: "THIS CANNOT BE REAL."

That reaction is fuel for a sharp Us vs. Them dynamic in e-sports culture, forged through years of enduring ridicule from fans of traditional sports. (In 2015, when YouTube launched a dedicated channel for gaming, late-night host Jimmy Kimmel joked that it was called "The 'We should all be very ashamed of ourselves for failing as parents' Channel.")

But as a product of the online world, e-sports is a media creation as much as it is a sports phenomenon. Marketing is in its DNA. Just as with YouTube celebrities, who form strong bonds with their fans by being themselves (or at least appearing to be), professional gamers often spill intimate details of their lives while streaming.

Meanwhile, the professional e-sports leagues produce slick video biographies of players, six- to 10-minute sketches uploaded to YouTube that are strikingly similar to the profiles of athletes that air during Olympic broadcasts.

At a panel discussion a couple of weeks ago sponsored by RBC, David Hopkinson, the chief commercial officer of Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment, which is gearing up to launch an e-sports version of the Toronto Raptors, explained the approach: "We've got to turn these athletes into personalities that the lay person and the community can relate to."

A video about Jordan (n0thing) Gilbert, who was a rifleman with Cloud9 until a few months ago, plays like an aspirational calling card for the entire tribe of amateur

Counter-Strike players. Opening on a silhouette of Gilbert on the beach at sunset – an uplifting, anthemic guitar jangling on the soundtrack – we cut quickly to snippets of praise from each member of the family: his supportive mom, skeptical father and protective older brother. Jordan says that video games attracted him in part because, as a kid who was small for his age, he found it tough to compete in traditional sports such as hockey. The camera watches as he strolls by yachts moored at a marina and as he kids around with his brother at a golf driving range.

"He started playing and he was able to make this career out of what he loved to do," says his brother, as we catch a glimpse of Jordan during a tournament, bathing in the adoration of fans. "Just seeing that you're actually able to live a dream is pretty inspiring."

Another video, about the Detroit-based player Spencer (Hiko) Martin, swoops from low to high – the hard economic times his family endured when that city's automotive industry hit the skids and then to his work raising money for a local hospital to buy a video-game setup for juvenile patients. It also notes that, at an especially low moment in his career, Martin almost quit playing entirely, but was encouraged to stay in the game by fans sending him messages of support online.

Fans are at the core of e-sports' evolution, and their ability to gather critical mass online – on Twitch, Twitter or other online platforms – gives them a sense of power that fans of pro sports have never had. The leagues, sponsors and media companies know they need to step lightly.

"It's not just a game you play, there's a cultural component to it," noted Jason Badal, the senior director of business affairs for Sportsnet, which began streaming e-sports games in the fall exclusively on the network's app. "We'd rather be slow and gain credibility, rather than just try to monetize or turn it into an industry. With this group, you have to."

At Northern Arena, the tournament went the way Sascha feared it would: Cloud9 marched through the early rounds and then collapsed in the final match late on Sunday afternoon, losing to the Brazilian team known as Immortals. He took it hard.

But as we rode the subway home, he put his head on my shoulder, the weight of his dashed dreams growing heavy – and I thought back to the previous night. The matches had gone late, and by the time we slipped out of the back doors of the convention centre, it was almost midnight; a wispy quiet had descended on the area. Sascha began to tell me about a player he admired, a Ukrainian rifleman with the tag name "s1mple" who, as a teen, had realized there wasn't enough opportunity to go professional in his home country, so he left his family and girlfriend in order to join a U.S. team.

Sascha mentioned one moment that helped make s1mple a legend: He found himself in what is known as a 1 v 2 situation, where he was the only player alive on his team, facing off against two others. In a situation like that, usually the round would end in a "trade-out": in killing one of the opposing players, he would reveal his location and end up getting himself killed. But in this case, s1mple dropped himself off of a ledge, spun around and shot one guy, then pivoted instantly and killed the other one, all without the aid of a rifle scope. It sounded to me like Luke Skywalker taking down the Death Star without instruments.

I listen to Sascha talking about this manoeuvre – and ask him about how players move in CS:GO – and he's talking about strafing and leaps and flashbang grenades, and the words are just flying by and I don't think I understand even half of them, but what I do know is that I'm in the presence of pure 15-year-old boyish joy, and his ardour for the game is radiating like steam off a sidewalk after a summer rain. His awe for the players, his affinity with them, his respect for their deep skill, his raw teenaged enthusiasm, are contagious. Familiar.

And I'm carried back 40 years, sitting next to my brother watching Hockey Night in Canada in black and white while our parents are out for the evening and we're thrilling to Borje Salming's shot blocks and Mike Palmateer's cartwheel poke-checks and Darryl Sittler's finesse. And everything still seems possible.