Two years ago, Marina Elliott was a graduate student at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver when she answered an ad on social media for a dig in South Africa. The project needed paleoanthropologists who were also serious climbers. The rub: Applicants had to be slender enough to wriggle through a long series of underground fissures as narrow as 18 centimetres across.

Their task would be to examine a newly discovered rock chamber where recreational cavers had reported what looked to be some very old bones. “I spent some time shoving myself under various pieces of furniture at home and thought, yeah, I can do that,” she said.

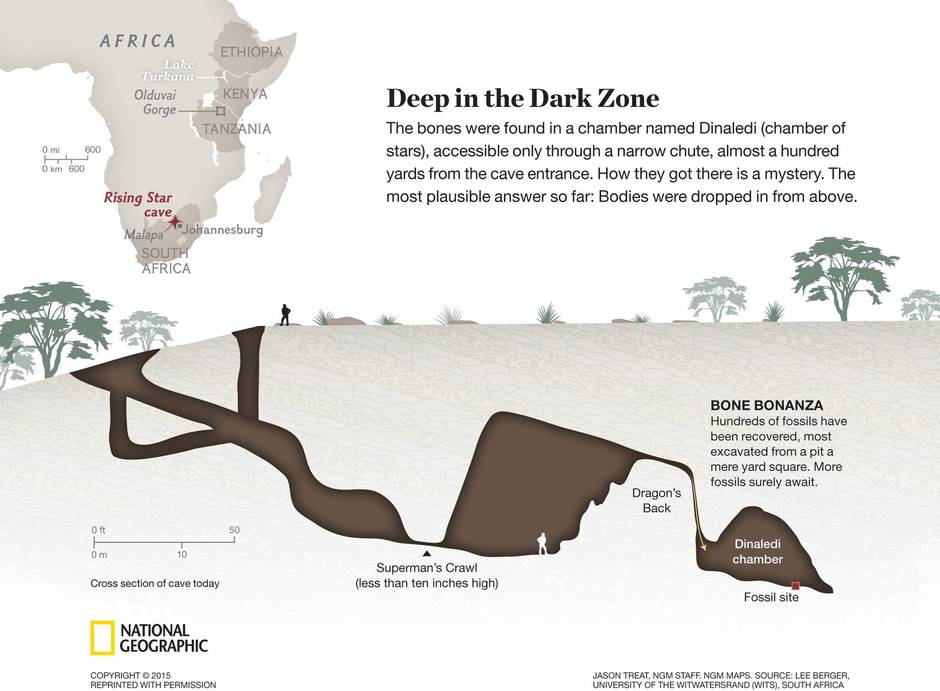

A few weeks later, as part of an all-female team of excavators selected by the project, she became the first scientist to squeeze into the chamber, in the Rising Star cave system about 50 kilometres northwest of Johannesburg. What she saw would prove to be the discovery of a lifetime – one that is rattling conventional wisdom about how and when our ancestors, and perhaps others, first began to pay special regard to their dead.

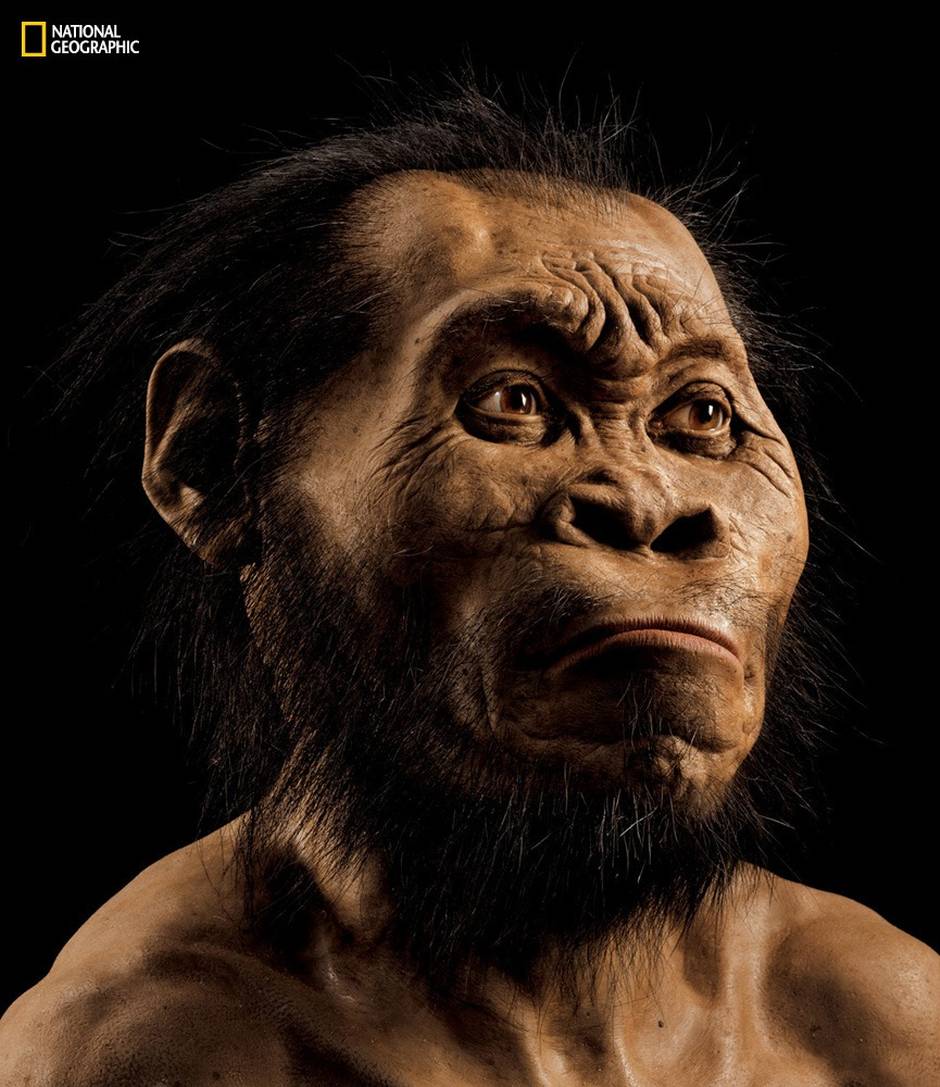

In a series of findings un-veiled on Thursday, researchers involved in exploring the chamber said it contains the remains of a previously unknown species of hominin, the evolutionary group that eventually gave rise to Homo sapiens. Dubbed Homo naledi, after the Sesotho word for “star,” the species appears to be an early and possibly founding member of the human line.

The remains have not yet been carbon-dated, but they include a mixture of physical features that suggest the creature emerged between 2.5 million and 2.8 million years ago, effectively bridging the gap between the Homo line and the more primitive Australopithecines that came before.

The discovery is unusually comprehensive, based on 15 individual skeletons painstakingly extracted from the chamber, including both male and female specimens that range in age from infant to older adults. The features of the skeletons are so similar that they suggest familial relationships, researchers say, and by all appearances the chamber contains many more.

“You can’t even imagine the density and volume of material that’s down there,” said Dr. Elliott, who is now a post-doctoral researcher with the project based at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.

Yet even more intriguing than the number of individuals present is the mystery of how they got there. The chamber has yielded no trace of fire, tools or animals bones apart from the homonins. It is highly improbable that the individuals found within were living there, said paleoanthropologist Lee Berger, who led the work.

“We have come to the conclusion that this chamber is likely a difficult-to-reach, deliberate body disposal site,” Dr. Berger said.

The bones show no signs of rough treatment, such as breaks and cut marks that might indicate cannibalism or some type of prehistoric confinement. But their arrangement and their relationship to the sediment in the cave reinforces the idea they were placed as corpses over a long period of time.

Various forms of ritual burial have been documented among ancient humans and their closest cousins, the Neanderthals. But Homo naledi would have come long before, and was a far different creature, Dr. Berger said.

“We would argue that something with such a small brain and a very different body plan is not a human,” he said, yet the chamber suggests some form of “ritualized, repeated behaviour” with the dead.

The chamber has now been sealed, Dr. Berger said, to give researchers time to take stock of what they found and leave open the possibility that much more will be discovered as new techniques and tools are developed to deal with the complex and dangerous site. Meanwhile, samples of Homo naledi are expected to be analyzed to better pin down their age and see whether ancient DNA can be extracted to establish where the species fits into the hominin family tree.

The work is supported by National Geographic and published in the open access research journal eLife. A documentary about the discovery, featuring the efforts of Dr. Elliott and her teammates, is scheduled to air on PBS on Sept. 16.