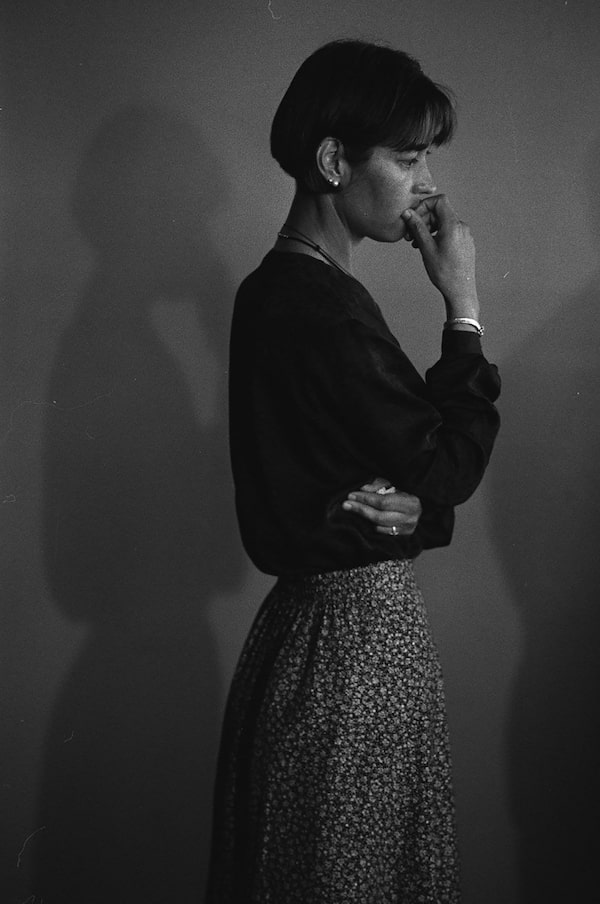

Sister Dianna Ortiz on April 22, 1996. Ortiz, an American Roman Catholic nun whose rape and torture in Guatemala in 1989 helped lead to the release of documents showing American involvement in human rights abuses in that country, died on Feb. 19, 2021, in hospice care in Washington. She was 62.STEPHEN CROWLEY/The New York Times

Dianna Ortiz, an American Roman Catholic nun whose rape and torture in Guatemala in 1989 helped lead to the release of documents showing U.S. involvement in human-rights abuses in that country, died on Feb. 19 in hospice care in Washington. She was 62.

The cause was cancer, said Marie Dennis, a long-time friend.

While serving as a missionary and teaching Indigenous children in the western highlands of Guatemala, Ms. Ortiz was abducted, gang-raped and tortured by a Guatemalan security force. Her story became even more explosive when she said someone she believed to be an American had acted in concert with her abductors.

Only after years of extensive therapy at the Marjorie Kovler Center in Chicago for survivors of torture did Ms. Ortiz start to recover, at which point she began to hunt down information about her case. She went on to become a global champion for people subjected to torture, and her case would help compel the release of classified documents showing decades of U.S. complicity in human-rights abuses in Guatemala during its 36-year civil war, in which 200,000 civilians were killed.

It was never clear why she and many other Americans were targeted. She was told at one point that hers was a case of mistaken identity, an assertion she did not believe. Her attack came during a particularly lawless period; ravaged by war, Guatemala was being run by a series of right-wing military dictatorships, some of them violent toward Indigenous people and suspicious of anyone helping them.

Ms. Ortiz’s 24-hour ordeal, initially labelled a hoax by U.S. and Guatemalan officials, included multiple gang rapes. Her back was pockmarked with more than 100 cigarette burns. At one point she was suspended by her wrists over an open pit packed with the bodies of men, women and children, some of them decapitated, some of them still alive. At another point she was forced to stab to death a woman who was also being held captive. Her abductors took pictures and videotaped the act to use against her.

The torture stopped, she said, only after a man who appeared to be an American – and appeared to be in charge – saw what was happening and ordered her release, saying her abduction had become news in the outside world. He took her to his car and said he would give her safe haven at the U.S. embassy. He also advised her to forgive her torturers. Fearing he was going to kill her, she jumped out.

The trauma left her confused and distraught. She had become pregnant during the assaults and had an abortion. As often happens with people subjected to torture, much of her memory of her life before the abduction was wiped out. When she returned to her family in New Mexico and to her religious order of nuns in Kentucky, she did not know them.

“To this day I can smell the decomposing of bodies, disposed of in an open pit,” she said in an interview in the late 1990s with Kerry Kennedy, president of Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights, an advocacy organization. “I can hear the piercing screams of other people being tortured. I can see the blood gushing out of the woman’s body.”

When she suggested her abductors were supervised by an American, she was smeared. “The Guatemalan president claimed that the abduction had never occurred, simultaneously claiming that it had been carried out by nongovernmental elements and therefore was not a human rights abuse,” she said in the interview with Ms. Kennedy.

Ms. Ortiz filed Freedom of Information Act requests. She pressed her case in U.S. and Guatemalan courts. In 1995, a federal judge in Boston ordered a former Guatemala general to pay US$47.5-million to her and eight Guatemalans, saying they had been victims of his “indiscriminate campaign of terror” against thousands of civilians. (She never received the money.)

She recounted her story to the news media and participated in protests to urge the U.S. government to release its files on her. In 1996, she began a five-week vigil and hunger strike across from the White House seeking the declassification of all U.S. government documents related to human-rights abuses in Guatemala since 1954.

In a little-noted moment, Hillary Clinton, at the time the first lady, met with Ms. Ortiz during her hunger strike. Ms. Kennedy said in a phone interview that Ms. Clinton’s prodding had helped lead to the release of government papers regarding Ms. Ortiz.

The files were heavily redacted and did not reveal the identity of the American or by what authority he had access to the scene of her torture. But Ms. Ortiz’s case became part of a sweeping review of U.S. foreign policy and covert action in Guatemala during the Reagan, Bush and Clinton administrations.

Over time, declassified documents showed Guatemalan forces that committed acts of genocide during the civil war had been equipped and trained by the United States.

“Dianna shined a huge spotlight on the fact that the United States government, through the CIA and military intelligence, was working hand in glove with the Guatemala military intelligence units,” Jennifer Harbury, a close friend, said in an interview. Her husband, a Guatemalan commando, had been killed during the civil war.

In 1999, then-president Bill Clinton apologized for the U.S.’s involvement.

Ms. Ortiz’s book, The Blindfold’s Eyes: My Journey from Torture to Truth (2002, with Patricia Davis), recounted the psychological toll that both the abduction and her quest for the truth had taken on her.

And at some point, her friends said, she realized that she had to stop, for her own sanity.

“It was so exhausting for her; she had to pull back, or it was going to do her in,” Meredith Larson, a friend and fellow human-rights activist who was also attacked in Guatemala, said in an interview.

Ms. Ortiz stopped agitating for information in her own case, Ms. Larson said, but she became a champion of torture survivors, remaining active in torture-related causes.

“She has moved our collective consciousness on how destructive torture is and how important it is to support the well-being of survivors,” Ms. Larson said.

Dianna Mae Ortiz was born Sept. 2, 1958, in Colorado Springs, Colo., and grew up in Grants, N.M., one of eight children. Her mother, Ambroshia, was a homemaker; her father, Pilar Ortiz, was a uranium miner.

She leaves her mother; her brothers, Ronald, Pilar Jr., John and Josh Ortiz; and her sisters, Barbara Murrietta and Michelle Salazar. Another brother, Melvin, died in 1974.

Dianna yearned for a religious life from an early age, and in 1977 she entered the Ursuline novitiate at Mount Saint Joseph, in Maple Mount, Ky. She then became a sister of the Ursuline Order. While undergoing her religious training, she attended nearby Brescia University, graduating in 1983 with a degree in elementary and early childhood education. She taught kindergarten before going to Guatemala in 1987.

In 1994, she moved to Washington to work for the Guatemala Human Rights Commission. There she met others who had lost loved ones to torture or who had been tortured themselves, and they started a group called Coalition Missing to draw attention to those who were killed or disappeared in Guatemala.

She later helped found the Torture Abolition and Survivors Support Coalition, which became a global movement.

“What we saw was a woman of incredible courage and integrity who literally came back from the dead,” her friend Dennis said in an interview. “It was a struggle for her for years and years not to be pulled back into that awful place. But she claimed life and was able to do phenomenal work.”