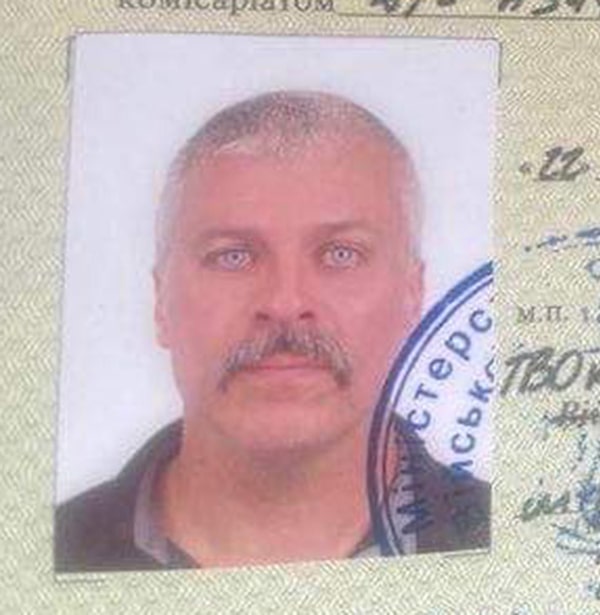

On his Ukrainian military identification, Robert Semrau looks older and greyer than the last time he served in an army, more than a dozen years ago. But even at age 49, this Canadian with a set jaw and steely gaze was ready to fight.

That, in the end, was all that mattered to the Ukrainian military intelligence officers charged with screening foreigners looking to enlist in the International Legion for the Defence of Ukraine, an assortment of fighters from around the globe helping to resist the Russian invasion. Mr. Semrau’s controversial background – he was dishonourably discharged from the Canadian military for shooting and killing an injured Taliban fighter in Afghanistan in 2008 – apparently didn’t matter to the Ukrainians back in June when Mr. Semrau enlisted.

Mr. Semrau’s military identification shows he joined the part of the International Legion commanded by Ukraine’s military intelligence service, the GUR. Two other Legion units, the 1st and 3rd Battalions, are attached to Ukraine’s regular armed forces. Each has about 500 fighters, according to Ukrainian media.

Robert Semrau's Ukrainian military ID.

Mr. Semrau in Gatineau, Que., during court-martial proceedings in 2010.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

Current and former members of the International Legion who spoke to The Globe and Mail say Mr. Semrau, who left the Legion last month shortly after The Globe began asking questions about his presence in Ukraine, is representative of what is informally referred to here as “The Zoo” – a motley collection of adventure seekers, criminals, and con artists who have come to Ukraine seeking glory, reinvention, and redemption.

Mr. Semrau’s backstory is unique, but not entirely remarkable in the ranks of the Legionnaires. Among the others known to have joined the fight for Ukraine are Rhee Keun, a 38-year-old South Korean special-forces veteran with a large YouTube following, as well as a conviction for sexual assault back home, and Tristan Nettles, a 34-year-old U.S. Marine Corps veteran notorious in Thailand for using his girlfriend to unwittingly transport drugs and then leaving her to face a lifetime jail sentence.

Several foreign fighters espouse far-right beliefs on their social media accounts. One tattoo-covered Canadian fighter, who met with The Globe, drunkenly gave several fascist salutes in the middle of a Kyiv pub while talking loudly about his hatred for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Another Canadian who travelled to Ukraine was retired lieutenant-general Trevor Cadieu, who was on course to take over as the top general in the Canadian army last year before allegations of sexual misconduct dating back to 1994 emerged. He was charged in June with two counts of sexual assault.

Legion sources say Mr. Cadieu – whom Russian propaganda channels claimed was playing a role directing the prolonged Ukrainian defence of the Azovstal steel factory in the city of Mariupol – was never a member of any of its three battalions. A diplomatic source told The Globe that Mr. Cadieu, who has denied the allegations against him, has now returned to Canada.

Mr. Semrau didn’t reply to messages requesting an interview, though a member of the Legion said Mr. Semrau told others that he had received them.

Mr. Cadieu also declined to be interviewed. “I respectfully prefer not to comment at this time on support to Ukraine,” he wrote in reply to a LinkedIn message.

Trevor Cadieu, then a brigadier-general, looks on as the Grey Cup arrives at CFB Edmonton in 2018.Jonathan Hayward/The Canadian Press

Many of the Westerners serving in the International Legion view themselves as descendants of the foreign volunteers George Orwell described fighting in Spain’s 1930s civil war: “A thin line of suffering and often ill-armed human beings standing between barbarism and at least comparative decency.”

In reality, the Legion is more valuable to Ukraine for the media attention it brings – helping to deepen the connections between Ukraine and the West – than the largely supporting role they have played on the battlefield thus far.

Legionnaires said the 1st and 3rd battalions were often assigned to hold a quiet part of the front line, freeing up Ukrainian troops to fight elsewhere. Foreign fighters attached to the GUR, meanwhile, were used in riskier missions, such as entering recently liberated towns and villages, looking for remaining pockets of Russian resistance.

Those who come from afar to fight for Ukraine are often running from something somewhere else.

“Ninety per cent of the Legion has served well, served faithfully. They took enemy fire for months, and now they’re on the offensive,” said one American member of the Legion’s special-forces battalion, which participated in the recent Ukrainian counteroffensive that drove Russian troops out of the eastern Kharkiv region. “But then you have that 10 per cent of criminals and crazies who should never have been here. People like Robert [Semrau] who want to establish their honour.”

Others have a harsher assessment of the Legion as a whole. “Honestly, I’d send most of them home,” said another American fighter who is of Eastern European descent and, unlike most of the foreign fighters, speaks Ukrainian. After initially joining the Legion at the start of the war, he quit and joined a regular Ukrainian military unit.

An International Legion of Ukraine patch.Anton Skyba/The Globe and Mail

The Globe isn’t naming the Legion members who agreed to be interviewed because they are forbidden by their commanders from speaking to media. Some would face legal trouble in their home countries if it was revealed that they were fighting in Ukraine. Canada has barred members of the military and civil service from participating in the conflict.

Though they are described in Russian state media as “mercenaries,” Legion members are paid the same salaries as their counterparts in the regular Ukrainian army – just under $900 per month, plus combat bonuses for frontline duty that can double or triple that income. The units are commanded by Ukrainians, and the highest rank any foreign fighter can hold is lieutenant.

Prior to February’s launch of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, fighters from Chechnya and Georgia – two other parts of the former Soviet Union that have struggled to assert their independence from Moscow – had formed battalions to aid Ukraine in the war for the southeastern Donbas region, which began in 2014.

But it was only after Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky issued a Feb. 27 call for foreigners to “come and fight side by side with the Ukrainians against the Russian war criminals” that Western fighters began arriving en masse.

Echoing those who fought against fascism during the Spanish Civil War, or those who more recently travelled to Iraq and Syria to join the battle against the so-called Islamic State, the fighters The Globe met in Ukraine see themselves as fighting on the front line of a good-versus-evil struggle. The question, in more than a few cases, is whether they’re helping or hurting their chosen cause.

“People think they can help because they were in the military, or really good at Call of Duty,” the American fighter of Eastern European descent said, referring to a popular combat-themed video game. “But you can’t do much if you can’t speak the language, don’t know the culture. I’m pretty confident that people died or were captured because of stupidity, because they got separated from their units and couldn’t ask the locals which way were the Russians, and which way were the Ukrainians.”

Some Legion members and ex-Legion members are known to be in financial distress, making them potential targets for Russian intelligence operations. In April, someone leaked the entire list of International Legion members, including the names, birthdates and passport numbers of 33 Canadian citizens, ranging in age from 19 to 64. The list was later published by a Russian pro-war Telegram channel.

The only Canadian known to have been killed so far in the fight for Ukraine, 31-year-old Émile-Antoine Roy-Sirois, was not among the 33 names on the list. Nor were any of the Canadian fighters The Globe has met in Ukraine.

One American fighter, who went by the nom-de-guerre Benjamin Velcro, is reviled by his former comrades for giving interviews, after quitting the Legion and leaving Ukraine, to pro-Russian media outlets that echoed Kremlin propaganda about Ukraine.

Emese Fajk, codenamed Mockingjay, is the communication liaison for the international legion.Anton Skyba/The Globe and Mail

Even the public face of the Legion – a young woman who goes by the Hunger Games-inspired code name Mockingjay – has an awkward past. Australian media recognized the Legion’s press officer as the Hungarian-born Emese Fajk, a 30-year-old that Australia’s tabloids had dubbed an “international conwoman.” Ms. Fajk shot to fame in Australia two years ago by submitting the highest bid on a reality TV show called The Block, which sees contestants compete against each other to renovate and then auction off their homes, with the winner being whoever can draw the biggest offer for their renovated home.

Ms. Fajk, who described herself on the show as a cybersecurity expert and claimed to have done consulting work for Apple and the United Nations, never paid the winning US$4.3-million bid. She allegedly submitted fake banking screenshots to the show’s producers to convince them the money was en route, but it never arrived.

In a letter addressed to Lieutenant-Colonel Igor Zinin, the commanding officer of the 1st Battalion of the International Legion, a dissident member of the Legion said the presence of Ms. Fajk, among others, was “a serious and significant risk to the national security of Ukraine” since they could potentially be compromised by Russian intelligence.

In an interview, Ms. Fajk called her misadventure on Australian TV “an artificially created scandal” and said she did indeed have the money and that she only failed to transfer the cash because the show’s producers gave her the payment information after the deadline had passed.

Ms. Fajk acknowledged that the Legion had trouble screening the first volunteers who arrived after Mr. Zelensky’s call for help, but said more recent arrivals were now being properly vetted. “If you start going around any country’s regular army – just like with all citizens – you will find people who come from difficult backgrounds, let’s call it that. And in any army, you will find people who have the views that you don’t necessarily agree with. You will find the people who may even have a criminal background that somehow they concealed or slipped through. There is no army where everyone is happy, everyone is normal and everyone is, you know, model citizens.”

Foreign fighters prepare to take a new position near the town of Lyman in Donetsk on Oct. 2.Ivor Prickett/The New York Times

Other intrigues swirl around Ukraine’s foreign fighters. Several Canadians who came to Ukraine said they tried in vain to make contact with the Canadian Ukrainian Brigade, a unit that was launched with great fanfare early in the war, and which continues to collect donations online despite no evident presence on the ground. The same was said about the Norman Brigade, a Canadian-led unit which raises money on Twitter and Facebook selling war-versus-Russia merchandise. Both units were described by Canadians fighting in Ukraine as “urban legends.”

However, the commander of the Norman Brigade – a Canadian military veteran from Quebec who goes by the nom-de-guerre Hrulf – told The Globe that his unit still existed and was in the process of being folded into the regular Ukrainian army. Hrulf said the Norman Brigade plans to relaunch with stricter standards, including two months of training as a unit, in an effort to overcome the fact that many of the foreign fighters who came to Ukraine had impressive individual skills, but no experience fighting together.

Vera Mironova, a Ukraine-based expert on foreign fighters in the Middle East and elsewhere, said the first days and weeks after Mr. Zelensky decreed the formation of the Legion were “chaos” that allowed an array of people to come into Ukraine without any systemic examination of who they were, and whether they would be assets or liabilities to Ukraine’s war effort. “We have very good fighters who honestly came to defend Ukraine. But the problem is that a lot of them are here for God-knows-what personal reasons. And the screening mechanism is not working, at best – actually, it is non-existent,” Ms. Mironova said. “It’s too late to actually fix it on the border, because everyone who wanted already entered. So right now, security is busy running around post facto, trying to figure out who those people are and what they’re here for.”

She said that many of those who arrived to fight in Ukraine had come directly from the last “fight-for-freedom” cause célèbre, the Kurdish YPG militia that fought in Northern Syria against both the Turkish military and the remnants of the so-called Islamic State in recent years. There were enough YPG veterans in Kyiv this summer that they held a reunion party, Ms. Mironova said. Separately, Ukrainian security sources are concerned about the intentions of a group of Chechen jihadists – commanded by Abdul Hakim al-Shishani – who recently arrived in Ukraine after years of fighting in Syria against the Russian-backed regime of Bashar al-Assad. In Syria, the Chechen fighters were allied with the extremist al-Nusra Front.

A former YPG office in Tel Abyad, Syria, in 2019. Many veterans of the Kurdish forces in Syria are now also involved in the war in Ukraine.Khalil Ashawi/Reuters

It was amid the early chaos that controversial characters like Mr. Semrau and Mr. Cadieu arrived. One Canadian member of the International Legion said that while he never encountered Mr. Semrau in the field, he would have been uncomfortable serving alongside him. “I don’t think anybody wants the PR associated with him,” said the Canadian fighter, who is from Alberta. “What he’s convicted of is conduct that no soldier should be a part of.”

The Albertan said his own unit consisted of brave fighters that he believed had helped tilt the course of the war. A sniper, he took part in the recent counteroffensive that liberated the Kharkiv region after more than six months of Russian occupation. At least one member of the Legion, Irishman Rory Mason was killed in early October in the Kharkiv area, one of at least 32 foreigners who have died fighting for Ukraine.

The Albertan, who had a post-military career as a private security contractor in the Middle East and North Africa, said the fighting in Ukraine was completely different from anything he or most other foreign fighters had experienced.

His role at times has been “just literally hunting human beings” – creeping up on unsuspecting Russian troops and looking for an officer to kill. “It was very, very sombre … it made me really think of World War Two, when the enemy was that close, and your snipers were the only thing that could reach out and touch them.”

Veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq – where Western armies spent most of their time suppressing insurgencies – have found that those experiences don’t translate to a conflict dominated by long-range artillery and rocket fire. “We are on a very different end of the war than we were in the Middle East. We don’t have air support here. We don’t have direct fire support. If I want to call in artillery here, I’m talking like in six to 12 hours I might get some artillery support.”

Canadian veteran Jay T. Foules and another foreign fighter he met in Ukraine, wearing a mask from the video game Call of Duty.Handouts

Jay T. Foules is a veteran of Afghanistan and the Balkan wars who travelled to Ukraine in March to see if his skills as a combat engineer were needed. The 50-year-old Ottawa resident was nearly killed in June when the vehicle he was driving backed over an anti-tank mine in the southern Zaporizhzhia region.

Despite injuries, including a broken neck, the loss of much of his left arm, and hearing problems, Mr. Foules said he has no regrets about going to Ukraine. He says he met some bizarre characters among the foreigners there, such as one who arrived at the training base wearing a Call of Duty skeleton mask, as though the video game was his inspiration for joining the war against Russia.

But Mr. Foules said the men in his unit, which included Mr. Nettles, the drug trafficker, were motivated to try to help any way they could after seeing television images of the war. “We just couldn’t watch those families and peaceful citizens get torn apart.”

Others admit that they came to Ukraine expecting that they would die thousands of kilometres from their home. They’re looking for redemption, even if it’s their final act.

One 26-year-old Ontario resident – who has already been wounded once in this war – said he had been abandoned in a parking lot by his father as a toddler. As a teenager, he says he sold cocaine to help his mother pay bills. Now he’s in Ukraine, hoping to impress his estranged ex-wife and kids, even if it’s the last thing he does.

“I know the risk. I know that I could die tomorrow. I just want to make the most out of my life,” he said in an interview in Kyiv before deploying to the front again after time away to recover from his injury. “If I can be here and I can stop a few Russian soldiers from raping or pillaging a village, from doing something bad towards Ukrainian citizens? Why would I not do that? Even if it takes my life.”

Mark MacKinnon

Mark MacKinnon