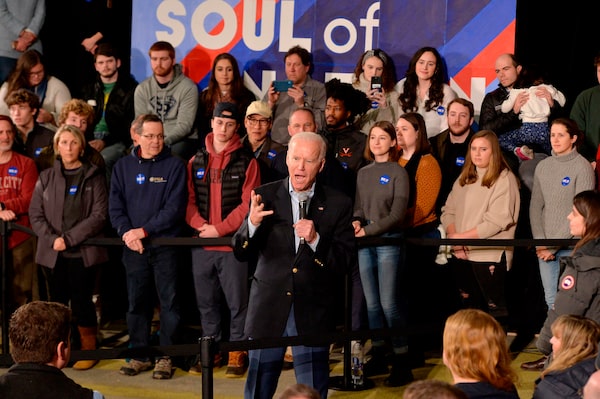

Joe Biden, seen here on Feb. 8, 2020, entered the race last spring as its undisputed front-runner, only to watch his rivals steadily narrow the gap.JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP/Getty Images

Joe Biden is struggling to find his message.

Speaking at the historic Rex Theatre in Manchester, N.H., he at first sounds subdued when discussing his prospects for the Democratic presidential nomination. “I know that nothing comes easy,” he says.

Suddenly, he’s shouting. “I don’t think Donald Trump – what he stands for – what, in fact, he believes – ” he begins, but doesn’t finish the sentence.

Then, describing his foreign-policy achievements, he rambles. “I did it by working to put together the nuclear Iranian deal. The Iran deal on nuclear – on limiting their nuclear – their efforts to gain nuclear capability.”

At times in this marathon contest, Mr. Biden has shown flashes of the sharp, impassioned campaigner of old. But this meandering, uneven performance has become increasingly typical of the former vice-president on the stump and in debates. It is also emblematic of his flailing bid.

The veteran politician entered the race last spring as its undisputed front-runner, only to watch his rivals steadily narrow the gap. He placed fourth in last week’s Iowa caucuses, the first vote of the competition. And in Tuesday’s New Hampshire primary, the final Suffolk University tracking poll has him more than 10 points behind Bernie Sanders and Pete Buttigieg, battling with Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar for third place.

With campaign contributions, media attention and political momentum all heavily susceptible to the influence of these early contests, Mr. Biden suddenly faces a prospect unimaginable just a few months ago: That he could stumble out of the race in its opening weeks.

“He’s a great man. He knows what he believes in. But his time has passed,” said Richard Auerbach, a 65-year-old lawyer, as he left the speech at the Rex. “He’s not the old Joe Biden.”

In a bid to save his candidacy, Mr. Biden has gone on the attack. He has trained most of his fire at Mr. Buttigieg, who is seeking to usurp the former vice-president as the race’s moderate. One ad mocks the relative inexperience of the 38-year-old former mayor of South Bend, Ind.

“Joe Biden led the passage and implementation of the Recovery Act, saving our economy from a depression,” a narrator intones. “Pete Buttigieg revitalized the sidewalks of downtown South Bend by laying out decorative brick.”

It is similar to the strategy Hillary Clinton unsuccessfully employed against Barack Obama in 2008. And the ex-president is exactly who the surging Mr. Buttigieg reminds his supporters of.

“He is Obama 2.0. He’s brilliant, he’s compassionate, he’s a pragmatic progressive,” said Carol McMahon, 70, a retired insurance agent who came to support Mr. Buttigieg at a presidential forum in a Manchester hockey arena Saturday night.

Of Mr. Biden, she shrugs. “There’s no inspiration there.”

In addition to their shared intellectual prowess – the Harvard and Oxford-educated Mr. Buttigieg speaks seven languages – he has Mr. Obama’s smooth rhetorical style. Speaking in precise paragraphs without notes, Mr. Buttigieg used the forum to contrast himself with Mr. Biden.

“Some are asking: ‘What business does the South Bend Mayor have seeking the highest office in the land?’ ” he said. “Americans in small rural towns, in industrial communities and yes, in pockets of our country’s biggest cities, are tired of being reduced to a punchline by Washington politicians.”

Mr. Sanders and Ms. Warren, meanwhile, have attracted armies of loyal leftists with ambitious promises of single-payer health care and free university tuition. And their supporters contend that Mr. Biden’s centrism will not be enough to motivate progressives to defeat Mr. Trump.

“Part of the reason the right-wing demagogue came about is because of bland, corporate candidates,” said Brian Owens, a 48-year-old civil servant, on the sidelines of a speech by Mr. Sanders at a union hall in Concord, the sleepy state capital.

It likely also hasn’t helped that Mr. Trump used his own impeachment trial to repeatedly air accusations that Mr. Biden engaged in corruption related to his son’s business interests in Ukraine, even though there is no proof that the former vice-president did anything wrong.

Emily Baer-Bositis, a political scientist at the University of New Hampshire, said Mr. Biden was always going to face an uphill battle in this state. For one, Mr. Sanders and Ms. Warren represent neighbouring states – Vermont and Massachusetts – in the Senate. And Mr. Sanders won New Hampshire by 20 points in 2016.

More difficult for Mr. Biden’s national prospects, she said, is that his central pitch as a seasoned statesman doesn’t resonate with the substantial portion of the Democratic base that is fed up with the status quo.

“Sanders and Buttigieg are those non-traditional presidential candidates who, while they are on different ideological wings of the party, both appeal to that same voter who is frustrated and wants something new,” Prof. Baer-Bositis said.

Not everyone, however, is put off by Mr. Biden’s cautious policies – or halting elocution.

Jeanine Conner, 60, an independent voter who has supported candidates of both major parties, said the former vice-president was the only Democrat that her Republican friends would go for.

“Joe Biden does not really do speeches well, but I’m not looking for an entertainer,” she said as the crowd milled about at the Rex after he spoke. “I’m looking for someone with experience. I’m looking for someone who can do the job.”

Adrian Morrow

Adrian Morrow