With all the sex and day drinking, it's a flat-out miracle that anyone in the offices of Mad Men's Sterling Cooper & Partners gets any work done. But amid all the drama, the creative team that until now was led by Don Draper actually managed to pitch ads to some clients. But are they any good? And what do they say about advertising? To celebrate Mad Men's final season, we award the first-ever Maddies, the coveted prize for the highs and lows of Draper and Co.'s advertising work.

Most insidious spin

Only Don Draper would see a link to cancer as a stroke of luck. In the first pitch viewers ever see him come up with on the show, he decides that the black mark on the tobacco industry is a chance for Lucky Strike to set itself apart.

“This is the greatest advertising opportunity since the invention of cereal,” Draper tells his clients, “…Everybody else’s tobacco is poisonous. Lucky Strike’s is toasted.”

In real life, Lucky Strike began using the “it’s toasted” tagline in 1917, and later used it to make dubious health claims.

The campaign shows that our man Draper could have had a brilliant career in political PR. But it’s also a gut-punch condemnation of the worst kind of advertising sweet talk: Just by telling people, “You’re okay,” Draper coldly explains, advertising can sell them anything. Even poison.

Biggest triumph of ego

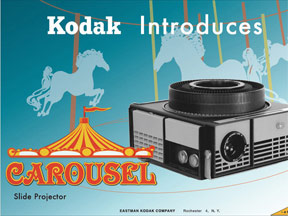

Agency colleague Harry Crane runs out of the room, crying, and Draper presents Kodak with “The Carousel” (the product’s real-life name), a nostalgic device to let us travel in circles through our most cherished memories. It’s a lot of pretty words, but it’s also an example of how Draper was often concerned more with burnishing his own mystique than with a client’s needs.

Still, for all its flaws, Draper’s pitch was smart. It recognized what Apple would later come to be known for: Not many people care about the technology. They care about what it does for them. Selling a revamped projector with deep emotion, as opposed to technical detail, would be at home in today’s ad environment.

Best reflection of contemporary sexism

Biggest rip-off