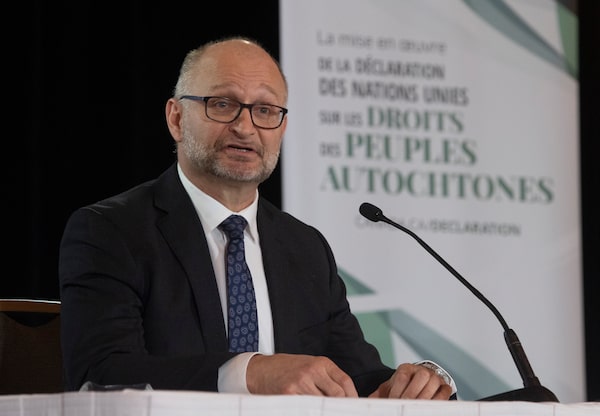

Justice Minister David Lametti delivers his opening remarks during an announcement about the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, in Ottawa, Thursday, Dec. 3, 2020.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

Take Two: Ottawa is again moving to codify the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canadian law. In this reshoot, the Trudeau government is spending a lot of time insisting its bill is both weighty and insubstantial.

The declaration, known as UNDRIP, is a non-binding resolution passed by the UN in 2007. At the time, Canada opposed it, as did Australia, New Zealand and the United States. Three years later, the Harper government reluctantly endorsed the document, but said it was merely “aspirational.”

In 2015, the Liberal platform promised to implement UNDRIP, but didn’t say how. Thereafter, an NDP private member’s bill wended its way to Parliament – “an act to ensure that the laws of Canada are in harmony” with UNDRIP. The House passed it in 2018, but it died a year later in the Senate.

The Liberals then promised a new government bill, and C-15 landed last week. The bill states that Ottawa “must take all measures necessary to ensure that the laws of Canada are consistent” with UNDRIP. What does that mean, exactly? What impact would UNDRIP have on existing law? Does it create new Indigenous rights, or new duties for the Crown?

The phrase “free, prior and informed consent” appears five times in UNDRIP’s 46 articles. A sixth variation appears in Article 32, which says states shall consult with Indigenous peoples and “obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands.”

Governments already have a constitutional duty to consult deeply with affected Indigenous groups in the case of projects with an impact on their rights. But UNDRIP’s language appears to go beyond that, which is why opponents see it as containing something more: A veto.

The Liberals insist that is not the case. Last week, Justice Minister David Lametti called worries “misplaced” and said “rumours out there” are baseless. “Meaningful consultation is what is embodied in free, prior and informed consent,” Mr. Lametti said. “The word veto does not exist in the document.”

The government’s position is that while it’s important to pass UNDRIP into law, doing so won’t change anything important in Canadian law. It’s an untenable position, though by the time the courts decide what UNDRIP means – a result which, years from now, will disappoint either backers or critics – the Trudeau government will be long out of office.

The problem is that the word “consent” has a meaning. It normally means the power to say yes or no, full stop.

A year ago, British Columbia passed UNDRIP into provincial law. At the time, Premier John Horgan acknowledged “consent is subjective” and said “courts may have an interpretation.” Not much has happened since. It’s still too early for a landmark court case.

The Trudeau government’s UNDRIP push has strong backing from Indigenous leaders, and from some in industry. Even the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers supports UNDRIP’s implementation, granted with a big asterisk that says “it must be done in a manner consistent with Canadian law and the Constitution.” Conservative-led provinces want Ottawa to slow down. Ontario’s Indigenous Affairs Minister warned of “sweeping implications.”

So who’s right? It’s impossible to say when looking at the bill’s current wording, and that’s the enigma at the heart of the UNDRIP debate. Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett introduced the bill as “an important roadmap for advancing reconciliation,” but it’s a map that could use some illumination.

Backers talk of the urgent necessity of passing the declaration into Canadian law, while at the same time saying it doesn’t change other laws. It’s pitched as a transformation of the relationship with Indigenous peoples, and also no big deal. Which is it? It can’t be both. If it doesn’t change anything about Canadian law, why do it? If it does, then what does it change, and is the change wise?

The Constitution entrenches Indigenous rights, including treaty rights, and a duty to consult Indigenous peoples about industrial development impacting rights. Those obligations were most recently sharpened in court challenges to the Trans Mountain oil pipeline. However, as the Federal Court reminded litigants, the Crown’s legal duty to consult, though extensive, does not “provide [opponents] with a veto over projects.”

Will UNDRIP rewrite settled Canadian law? The question is still unanswered.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.