Artist Ken Lum talks about his work, in Vancouver, in February, 2020.Rafal Gerszak/The Globe and Mail

Remai Modern in Saskatoon is currently showing a career survey of conceptual artist Ken Lum. The show entitled Death and Furniture, going to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto this June, includes several of Lum’s sculptures made from prefabricated furniture as well as photography and text works. Speaking from Philadelphia where the Vancouver native now teaches at University of Pennsylvania, he talked about our relationship to labour and to history.

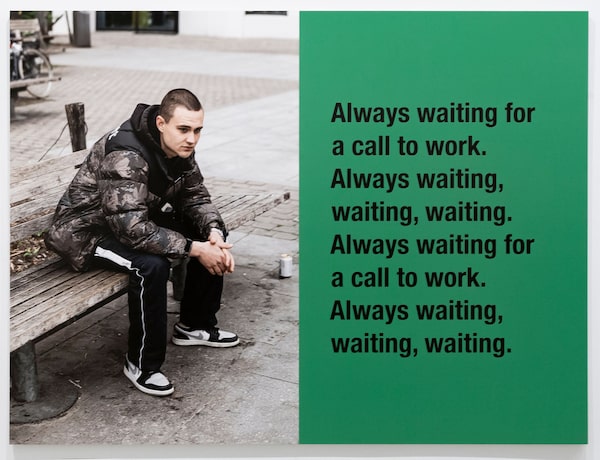

Let’s talk about Time. And Again, the most recent work in this show. It takes a fairly bleak view of labour, showing photographs of regular people with texts that suggest they are worrying about joblessness or undervalued for their work. It reminded me of your famous billboard Melly Shum Hates Her Job. Do most of us hate our jobs?

I don’t think people necessarily have to hate their jobs. I think people feel dissatisfaction or incompletion in life, of which their job is a big component. So it’s not even necessarily because of the job. It certainly is for many people in low paying jobs, the fast food industry and so on, but I think it’s also larger, more endemic than that. It has to do with this lack of spiritual satisfaction.

I’m Always Waiting, 2021, by Ken Lum. Part of the Time. And Again series. Installation view, Death and Furniture, 2022, Remai Modern, Saskatoon.Handout

Do you feel a lack of spiritual satisfaction in your job?

I always feel that in pretty well anything I do. I feel that way about the art world too, so it’s not exclusive to my work. I work in an Ivy League university; it’s the best university I’ve ever worked for. But on the other hand, everybody who works here is basically an alpha type. You have to be constantly working and producing. On the one hand, it’s incredibly fatiguing, but on the other hand, it’s also kind of exhilarating.

We think of you as a Vancouver artist. Will you return to Canada from Philadelphia?

It’s been 10 years; so it is long term. I like it here, but I need a job too. I sell most of my work but I’m more an artist that gets a lot of interest, a lot of respect. So that part is good, but you know at some point bills come in every month. I also like teaching.

I’m inspired by brilliant students all the time and I don’t have to be beholden to the art system.

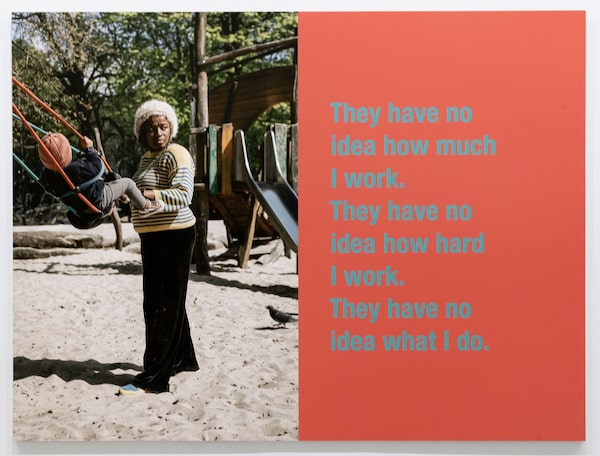

One of the figures in the Time. And Again series is a delivery person wearing a mask, with a text saying “I know I am lucky. I have a job.” Do you feel the pandemic has changed our relationship with work?

Oh, clearly it has in terms of people second guessing, about whether they wish to continue on with their jobs and pivoting to new reinventions of themselves. A lot of people don’t have the privilege of even considering whether they can pivot, but for those who can, there’s a lot of soul searching in terms of what they really want to do.

The system that we’ve put in place where we shift so much of the burden onto the most poorly paid, that’s clearly untenable. There’s a solution to a lot of unhappiness in terms of people’s gainful employment and that has to do with adequate pay and adequate benefits. You can go to Europe and people who are wait staff at restaurants, they do their job professionally and they’re there for a long time and turnover is relatively low. Why? Because they have benefits. People respect the position.

You have always used text in your work. What does it achieve for you?

I was a sign painter before an artist and text has this wonderful pictorialism. We know that from reading novels. I don’t read novels for the text. I read novels for the images that it imbues in my mind. Images themselves are full of textuality just as text is full of pictures.

They Have No Idea How Much I Work, 2021, by Ken Lum. Part of the Time. And Again series. Installation view, Death and Furniture, 2022, Remai Modern, Saskatoon.Handout

As you speak of that, I’m thinking of your Necrology series where you tell the stories of violent deaths entirely through retro typefaces without any pictures.

On the sesquicentennial of the death of Abraham Lincoln, the Philadelphia Inquirer reproduced the front page [from 1865.] It was: PRESIDENT ASSASSINATED. But then it had these subheads underneath: Son of Illinois. And then the next one: Civil War. And the last one was: A Nation Mourns. I’m not doing it justice, but it basically told the story of a life in no more than 100 words.

I was interested in the disappearance of a way of imagining. We live in the social media and smartphone age and there’s all kinds of acronyms – LOL – and that also provides ways of imagining. There are different ways for any given age, but I found it wistful, a little bit melancholic, this beautiful way of imagining a life that didn’t rely on a photograph or even any imagery.

Your work with the non-profit Monument Lab, looking at how history is represented in public spaces and has proved to be prescient. Monuments are being scrapped or names being changed all over the place.

Monument Lab started in my office in 2012, and now it’s grown to about 25 people, and a multimillion-dollar budget.

What’s your reaction to the recent toppling of the statue of “Gassy Jack” Deighton, the settler for whom Vancouver’s Gastown is named, and who married a 12-year-old Indigenous girl?

I think that there’s a lot of troubling histories that have been disguised by myth. And I think it’s healthy for a society to undisguise things.

But I also don’t think that the taking away of monuments on their own is constructive unless it is accompanied by genuine dialogue and reform and especially dialogue that seeks the input of those most aggrieved. And if there’s an absence of that, the removal of Gassy Jack, it achieves nothing.

Death and Furniture shows at the Remai Modern in Saskatoon to May 15 and opens June 25 at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto.

Line (foreground), 1986, 2022; six couches, by Ken Lum. Time. And Again series (background), 2021. Installation view, Death and Furniture, 2022, Remai Modern, Saskatoon.Handout

Sign up for The Globe’s arts and lifestyle newsletters for more news, columns and advice in your inbox.

Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor