Nick Sikkuark: Humour and Horror, a retrospective spanning the late Inuk artist’s 40-plus-year career now on at the National Galley of Canada, might not sound like March break programming. Indeed, its title could very well scare away some parents.

But if your kid – like my four-year-old – adores anything “spooky,” it’s ideal for a family visit. In fact, the exhibition in Ottawa begins with two rooms dedicated to a series of books, little known outside the North, that Sikkuark created in the early 1970s specifically for children.

My son and I happily spent half an hour in a reading area paging through these works, which feature caricatures of Inuk men with cheeky captions and vivid drawings of Arctic animals and fantastic beasts who voice complex human emotions in Inuktitut inner monologues.

This then framed our experience for the rest of the show. We were inspired to come up with our own funny and scary stories to tell each other as we moved on to look at the better known magical/monstrous metamorphosing sculptures Sikkuark, who was born in 1943, created once he became a full-time artist after being showcased alongside other Inuit creators at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. We did the same for the late-in-life drawings he created after health issues led him to stop sculpting, including such narrative-inviting pictures as The Bear Who Stole a Kayak (2003). (How’d that bear learn to paddle, anyway?)

Humour and Horror curator Christine Lalonde made the decision to start the show with the five children’s books during discussions with Sikkuark that took place shortly before his death in 2013. As she told me in an interview, Sikkuark’s “universe” as an artist is already clear in them: his desire to portray and relay his knowledge of growing up living and hunting on the land; his sense of humour related to coping with difficult situations; his unruly imagination; and his interest in the interchange between animals and humans.

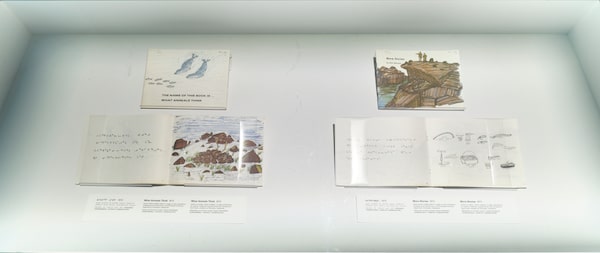

Commissioned by the Northwest Territories Department of Education, the books feature his handwritten Inuktitut syllabics opposite drawings made with felt-tip markers. Sikkuark – whom Lalonde describes as “central to the Inuit art development in the late sixties and seventies but also a little bit out of the mainstream” – made them while living in Whale Cove in the Kivalliq Region of what is now Nunavut, on the western shore of Hudson Bay.

Visitors to Humour and Horror, young and old, can interact with the books – Nick Sikkuark’s Book of Things You Will Never See; Hard Times, Good Times; Faces; What Animals Think; and More Stories – in several ways.

In Nick Sikkuark: Humour and Horror, a retrospective spanning the artist's 40-year career now on at the National Gallery of Canada, visitors can interact with Sikkuark's books.NGC

In the first room, original editions are under glass, available to peer at like the precious objects they now are. You can also sit down and gaze at enlarged images of the pages as they are projected one at a time onto the wall. (There are no original drawings: The books were printed on Gestetner duplicating machines, resulting in their destruction.)

In the second room, visitors can appreciate the books as intended and as seems most natural, by sitting down on a bench and paging through replicas created for the exhibition.

If you have a kid with you to make it socially permissible, you can read Sikkuark’s words aloud and break the contemporary (colonial?) taboo of raising your voice (and laughing) in an art gallery. (There are inserts of English and French translations of his amusing deadpan captions.)

The pictures in The Book of Things You Will Never See feel most connected to the sculptures Sikkuark developed his wider reputation for, and which are displayed in a later room of Humour and Horror. Made out of caribou antler, bone and fur, they too are of “things you will never see,” such as Untitled (Snow Worm?), a caterpillar-like creature standing upright and sticking out his fuzzy tongue; or Untitled (Caribou-human Transformation?), an unamused Inuk’s face popping out of the midsection of a reindeer.

Sikkuark’s sculptures are often untitled – those descriptions in parentheses are from Lalonde, question marks indicating interpretations – but the drawings in his books have accompanying monologues or dialogue that give psychological insight into his creatures and spirits. These beings confess to being confused as to why they have horns, or seem in denial that they have transformed into monsters, or express humiliation about their unusual form.

Sikkuark made sculptures out of caribou antler, bone and fur, such as Untitled (Caribou-human Transformation?), in which an unamused Inuk’s face pops out of the midsection of a reindeer.NGC/Handout

My son and I were both particularly sympathetic to a pair of duck-like creatures with the heads of an Inuk man and woman respectively, seemingly trying to swim their way off the page and out of sight.

What has happened to us?

We have turned into birds!

We don’t know what to do with our bodies.

We will have to feed ourselves where nobody will see us.

We are so ashamed!

Lalonde has put out other mass-market Inuit-written children’s books out in the reading room to enjoy alongside Sikkuark’s. We recognized a couple from our own bookshelves: A Promise is a Promise, a favourite terrifying tale about underwater child-snatchers by Michael Kusugak with Robert Munsch; and Sweetest Kulu, a beautiful poem to a newborn written by the throat singer Celina Kalluk. (We wished Sikkuark’s books were in print and available for purchase or at the library so we could read them again at home.)

Unlike the others, however, Sikkuark’s books had a particularly strong political purpose, as part a larger movement led by Tagak Curley, Jose Kusugak and Mark Kalluak that linked preserving and propagation of language to Inuit rights and self-determination.

Hard Times, Good Times is the most direct act of cultural reclamation. It transmits Sikkuark’s knowledge from his early years on the land with his Nattilingmuit parents, whom he lost to German measles when he was just six years old, a consequence of Canada’s intensified colonization of the North at the start of the Cold War. (The seeds of his sculpture practice were planted during those early years, when he was a child making toys out of caribou antler and seal bones.)

The bittersweet book also draws on the lives of other Inuit peoples who he encountered in his careers as a carpenter, subsistence hunter and artist across the vast North. “We are not of the same community or the same dialect, but we have many things in common,” reads an illustration of one such encounter. “We eat, sleep, think and struggle for life.”

Hard Times, Good Times also, it seemed to me, makes the strongest case that Sikkuark was a poignant poet as well as a visual artist. One page reads:

I am taking a road as direct as a nail and oh so rough.

I would like a smooth road so I could travel easily.

Someday I’ll get where I’m going, then I’ll be happy.

Reading Sikkuark’s words aloud, my thoughts often turned to the tragicomic plays of Samuel Beckett. Indeed, Inuk artist Tatanniq Lucie Idlout’s collective 662 OVA and Volcano Theatre are currently developing a Inuktitut translation and production of Waiting for Godot.

I visited Humour and Horror on the heels of having binged the recent season of HBO’s True Detective, which was itself a mixture of horror and humour. Set in Alaska but shot in Iceland, it has onscreen and soundtrack contributions from the Inuk throat singer/songwriter Tanya Tagaq. Its plot line is centred on the disappearance of a group of scientists in the North, and the major clue is the tongue of an Indigenous woman found at the scene of the crime.

Perhaps this is what made me especially notice the preponderance of stuck-out tongues in Sikkuark’s sculptures from the 1980s and 1990s, such as the twisted one of a contorted figure (Shaman in Transformation to an Eagle) and an unnerving one pointing straight up out of a clump of a creature crafted from a caribou skull, bone, ivory seal skin and fur (Fish Tongue Pointing to the Sky).

I wondered whether there was some thematic connection between these pieces and Sikkuark’s project through his children’s books to preserve his own “tongue” – Inuktitut – in a time of transformation for the North. Lalonde says that a protruding tongue leads to the sort of exaggerated distorted facial expressions that Sikkuark liked to create in his art. “He makes his faces funny or ugly, so we’ll get in close and wonder what he’s doing.”

As to any other symbolism, it’s one of the many questions Lalonde never got to ask Sikkuark because he died soon after the two met to start planning this exhibition, which ended up taking a decade to put together. “I wish I could have asked him, though he probably would have just smiled at me,” she says. “It was very purposeful that he would leave the story open.”

One of the first prominent sculptures Sikkuark created was the Queen’s Baton he carved from a narwhal’s tusk for the Commonwealth Games in 1978. But so many of his works are batons, passed to viewers to carry forward and continue the stories he started.

J. Kelly Nestruck

J. Kelly Nestruck