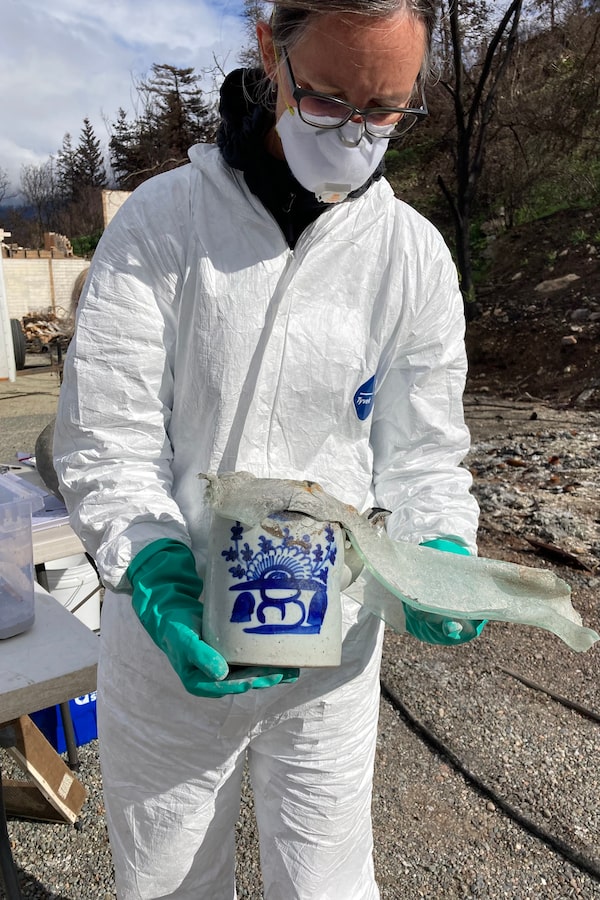

Conservators assess the damage to artifacts from the Lytton Chinese History Museum in Lytton, B.C., after a fire razed the town.Handout

More below • Lytton’s record-breaking heat, visualized

Hand warmers in their socks and pockets, a group of museum volunteers sifted through the remains of an inferno while wind like ice whipped through the Fraser Canyon. The site of what once was the Lytton Museum and Archives was grim: debris and ash everywhere. And then, a surprise among the incineration: a pile of magazines, singed around the edges. “But you could still see the pictures and turn the pages,” Heidi Swierenga says. “Heavily damaged, but the fire wasn’t able to penetrate that mass.”

Ms. Swierenga is senior conservator at the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver and co-founder of the British Columbia Heritage Emergency Recovery Network. Over the first two weeks of October, she and other members of the all-volunteer network travelled three times to Lytton, B.C., to search through the rubble of museums and other structures destroyed in the wildfire that swept through the town this summer.

On their first trip in, a reconnaissance mission, Tara Fraser was struck by the devastation to the land; black was everywhere. “It was really, really apocalyptic,” says Ms. Fraser, head conservator at the Vancouver Art Gallery. She describes a pattern of stone foundations and chimneys, and then, every once in a while, a spattering of bright yellow sunflowers. Or she’d move some ashes and underneath find a little weed or plant, bright green. “And I’m like, oh look at that. Life just wants to come through.”

BC HERN was there at the request of property owners and what they call heritage keepers, with logistical support provided by disaster relief organization Team Rubicon Canada. The volunteers’ aim was to salvage the cultural items they could dig up before the bulldozers move in, which had been expected to happen over the weekend, but was delayed.

The task seemed overwhelming at first.

“You get there, you stand on the edge and it looks like a bomb has gone off and that there can’t be possibly anything there,” said Ms. Swierenga, whose first stop was what used to be the Lytton Chinese History Museum.

“Yet if you look closer, you’ll see the skeletons of the display cases that originally housed the collection of ceramics. And then you’ll notice the ceramics embedded in the glass that has melted around them – the glass that used to be the shelving that they were sitting on.”

A conservator brushes an artifact with melted material on it.Anne Desplanches/Handout

Wearing protective equipment – that at turns left them freezing in the bitter Lytton wind or boiling under multiple layers – the BC HERN volunteers descended into the basement of the museum, where they sifted through about a foot-and-a-half of ash and all kinds of twisted metal. They worked their way through the site, creating pathways. They followed the directions of the owner, who was able to identify where precious items might be and steer them away from, say, the staff kitchen area. “And from there it’s really a matter of following the pattern of the fire. Some corners might have been more lightly touched, less heated, and there you will find more pieces that are intact,” Ms. Swierenga says.

It was the largest operation in BC HERN’s history. The consortium of arts and culture institutions was established in 2015 to assist with emergency preparedness, salvage training and recovery. “This is the first time we’ve participated in the loss of an entire town. There’s no power, there’s no water, there’s contamination throughout. It makes you have to think outside the box,” Ms. Swierenga says.

They were working not only in precarious conditions on the contaminated site (with snakes and black widow spiders to boot), but were up against a tight deadline. “When we were there, it was how much can we get done?” says Ms. Fraser, speaking after her third trip to the site last week. “They’re going to bulldoze this place in three days – what can we do? Oh the sun’s setting – can we keep going anyway? There was just this collective team approach to getting as much done as possible.”

Melted glass and charred metal are all that remains of the Lytton Chinese History Museum.Lorna Fandrich/lytton chinese history museum

Watching from the sidelines – because she wasn’t allowed down in the dig site – was Lorna Fandrich, the Chinese museum’s owner. She was feeling low as the search began on the first day. But then they started finding things.

A jade frog that used to have a coin in its mouth was one of the early discoveries.

“I think that was the first moment that made me smile,” Ms. Fandrich says. “Because it was something that I could say has history to it. It gave me hope that we would find other things.”

They did.

They found tiny wine glasses that had sat upon what would have been an altar table. They were a precious gift from Victoria-based author and historian Lily Chow, Ms. Fandrich’s mentor for the museum project.

Other thrilling finds included several so-called railway teapots, which were used in CP camps and had a sort of track design on the body. These teapots were among the first things Ms. Fandrich had wanted to collect. She managed to acquire seven of them before the fire. When they recovered the first one, they saw that shelving above it had melted and hardened right on the teapot, but they were able to pop the glass off. They found two others in good condition.

Heidi Swierenga holds a ‘railway teapot’ from the museum’s collection.Lorna Fandrich/lytton chinese history museum

At one point, Ms. Swierenga found a lid to a teapot and set it aside for safe-keeping. When a couple of hours later she found the matching pot, it felt like a triumph.

There were other gleeful moments, too.

“I remember having my back to what we called the pit,” Ms. Fraser recalls, “and I heard this big cheer. Everybody just all of a sudden let out this spontaneous cheering and whooping and I turned around and someone was carefully holding a big vase over their head. Everybody was so proud and it felt so rewarding, even if it was just one vessel.”

Each piece would be brought up to ground level where the team carefully washed contaminants off, dried the piece, wrapped it and placed it into a box. Most pieces were transported in a bucket pulled up to the surface with a rope. But some were so fragile that they would be carried up the ladder carefully by the volunteer who found it, in order to protect it for as long as possible. “If you touched it, it could literally, like petals on a flower, just fall apart,” is how Ms. Fraser describes one such piece.

There was a lot of improvising and problem-solving. Ms. Fraser found a large round vase that she needed to keep holding onto; if she let go, she felt it would fall apart. Other volunteers dismantled a headlamp and manoeuvred its straps around the vase and Ms. Fraser’s hands to maintain enough pressure to allow her to let go. They packed it that way, with the straps around the widest part.

Lytton is notoriously windy and at times the papers they were using for wrapping would blow away. “We were a little bit worried about the articles we were washing blowing off the tables,” Ms. Fandrich says.

Members of BC HERN and Rubicon Canada plan their process for salvaging items from the museum site.Lorna Fandrich/lytton chinese history museum

Ms. Fandrich built the museum in 2016 on land she bought in the 1980s to store rafts from her family business. She began hearing that a Chinese temple had once stood on the vacant lot. She did some research and found that the Joss House, a communal gathering space that included an altar for prayer, stood there from 1881 to 1928.

Ms. Fandrich is not Chinese, but felt a museum belonged on the site, and decided to do it herself with guidance from people such as Ms. Chow. It opened in 2017, telling stories about Chinese people who arrived in 1858 for the gold rush. Others came in 1882 and ‘83 to work on the railway. In 1928, the Joss House was sold to the person who lived next door, over objections from Chinese people.

All that history dismantled and rebuilt was destroyed again when fire ripped through the town on June 30. The wildfire killed two people and flattened most of the town, including the Lytton Museum and Archives.

A search last week through the remains of that institution was less successful. So much had survived from the Chinese museum because it was pottery. The archives were full of paper. And large debris: Charred and burned-out filing cabinets and metal shelving littered the place, along with chunks of the roof and deformed chairs and tables. It took several hours just to remove the contaminated, corroded and often sharp remnants of the eavestroughs.

There were also electrical cords and the remains of so many binders: just the metal spines and three rings. Everything else had been reduced to ash.

Still, the team uncovered some finds. A giant fossil. Arrowheads. Those magazines.

Some of the items recovered from the site.Heidi Swierenga/lytton chinese history museum

Funding for the operation was provided by Heritage BC’s Heritage Legacy Fund. The institutions that employ the volunteers – MOA, the VAG and also the Burnaby Village Museum and the Kelowna Museums – donated their employees’ time. Anne Desplanches, a conservator working in private practice, also volunteered.

Their experience will ultimately benefit their institutions. Among the lessons learned: Glass shelves could be problematic in a fire.

Glass has a lower melting temperature than ceramic, so volunteers would often find glass display shelves that had melted alongside ceramics that had survived. Sometimes the glass could be chipped off; in other cases it had dissolved and fused with the glaze layer. “And it was, ‘Oh my gosh, we have glass shelves throughout our museum,’ ” says Ms. Swierenga (although she adds that MOA also has a sprinkler system).

“It will absolutely, positively change how we approach our training,” Ms. Fraser says. “It will positively change how we approach disaster planning and response in our institutions.”

Both women noted the need for stable operational funding for the growing group, especially as climate change continues to affect cultural institutions.

Last Wednesday afternoon, as the mission was wrapping up, Ms. Fandrich was feeling grateful. She had been hoping to find five or six things. In the end, they found close to 200, about 40 of which are in good shape.

Ms. Fandrich is determined to rebuild. While the physical plans for the museum were lost – there was one set in the museum and another elsewhere in town; both burned – an architecture firm in Vancouver has offered to recreate them at no charge.

And when she does open again, some of these pieces, now wrapped in melted glass and twisted metal, will be part of a new display: one that tells the story of this fire.

“Midway through the first day of sifting, I had a little lull, when I just felt dismayed that all the collection was gone, all the pieces that people gave me personally from their family or their backyard were gone,” Ms. Fandrich says. “But then I think in the end I have peace with that. Because we did all we could to retrieve pieces, and they’ll tell a story in the new museum. They’ll tell the story of what happened to them.”

Lytton’s heat, visualized

A one-day snapshot of temperatures across Canada in late June reveals that the western heat wave was an extraordinary departure from what is typical in the region at that time of year.

Red areas indicate an air temperature rise of 10-15°C when compared to the 2014-2020 average.

Yukon

NWT

Grande

Prairie

B.C.

Alta.

Jasper

Lytton

Victoria

Temperature difference vs.

the 2014–2020 average

for June 27, 2021

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15°C

Daily temperatures for the

month of June, by year

N/A

20

25

30

35

40

45°C

Lytton, B.C.

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

Victoria, B.C.

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

Jasper, Alta.

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

Grande Prairie, Alta.

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

MURAT yükselir / the globe and mail,

source: government of canada; nasa

A one-day snapshot of temperatures across Canada in late June reveals that the western heat wave was an extraordinary departure from what is typical in the region at that time of year.

Red areas indicate an air temperature rise of 10-15°C when compared to the 2014-2020 average.

Yukon

NWT

Grande

Prairie

B.C.

Alta.

Jasper

Lytton

Sask.

Victoria

Temperature difference vs.

the 2014–2020 average

for June 27, 2021

U.S.

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15°C

Daily temperatures for the

month of June, by year

N/A

20

25

30

35

40

45°C

Lytton, B.C.

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

Victoria, B.C.

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

Jasper, Alta.

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

Grande Prairie, Alta.

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

MURAT yükselir / the globe and mail, source:

government of canada; nasa

A one-day snapshot of temperatures across Canada in late June reveals that the western heat wave was an extraordinary departure from what is typical in the region at that time of year.

Yukon

NWT

Nunavut

Grande

Prairie

B.C.

Red areas indicate an air temperature rise of 10-15°C when compared to the 2014-2020 average.

Alta.

Sask.

Man.

Jasper

Lytton

Victoria

Temperature difference vs.

the 2014–2020 average

for June 27, 2021

U.S.

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15°C

Daily temperatures for the month of June, by year

N/A

20

25

30

35

40

45°C

Lytton, B.C.

Victoria, B.C.

2021

2021

2020

2020

2019

2019

2018

2018

2017

2017

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

Jasper, Alta.

Grande Prairie, Alta.

2021

2021

2020

2020

2019

2019

2018

2018

2017

2017

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

June 1

5

10

15

20

25

30

MURAT yükselir / the globe and mail, source: government of canada; nasa

Sign up for The Globe’s arts and lifestyle newsletters for more news, columns and advice in your inbox.

Marsha Lederman

Marsha Lederman