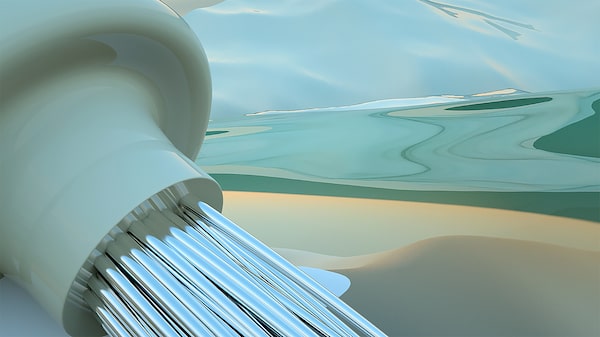

Anna Eyler, still from PAN/PAN, 2018.Courtesy of the artist/Handout

On mountainous Arctic shores, glistening pools of silvery water are home to creatures that look like spare parts of humanoid kitchen implements, combining steel and plastic with digits and hair. This is a futuristic northern landscape imagined by artist Anna Eyler; it was created using 3D imaging software to produce a short and silent video that grabs your attention with its indefinable weirdness.

The art work, entitled PAN/PAN, is displayed on a screen in the Toronto office of Equitable Bank, where it is intended for the enjoyment – or mystification – of employees.

Some Canadian banks collect paintings by blue-chip artists or hefty soapstone sculptures to decorate their boardrooms and hallways; not Equitable Bank, a branchless bank that launched a new digital platform in 2015. Since then, it has concentrated on collecting the work of Canada’s digital artists, acquiring about two or three new pieces every year to round out an art collection that also includes about 180 physical works.

“There was an obvious overlap,” curator Shannon Linde said in a recent interview. “Artists doing digital were facing some of the same challenges as the bank, moving into new territory.”

The collection, launched by Linde’s predecessor Lindsay LeBlanc and Equitable chief executive Andrew Moor, concentrates on works that probe and push the technology. “If you have a digital camera and take a picture, that is not necessarily digital art,” Linde said.

Instead, the bank collects stellar examples that experiment with media and question the role of technology. For example, artist Alison Postma plays with our perception of computer-generated imagery in a four-minute video loop depicting a clay cube continually imprinted with the artist’s fingerprints. Entitled A Point, A Line, A Surface, A Solid, it may look like CGI but it was actually produced using painstaking handmade claymation.

Linde also points to another example, a digital carpet created by Shaheer Zazai, an artist of Afghan heritage who renders the traditional woven pattern with pixels of red, blue and grey.

“Each knot is a piece of software punctuation,” Linde said, adding, “It’s hard to make a still digital image that captures attention, but this nails it. It’s questioning the technology, it’s got cultural context. It goes beyond.”

Much of the digital work that the bank collects comes to it through its annual prize for emerging digital artists, which it organizes in collaboration with the Toronto media arts centre Trinity Square Video. Every year, one winner receives $5,000 plus a residency at Trinity Square while four runners-up receive $1,000 and are included in a group show at the centre. (This year, recognizing the impact of the pandemic on artists, all five nominees received the grand prize amount). Winners have included Eyler for PAN/PAN in 2018 while Postma was one of the five 2020 winners.

Linde figures that digital artists are in particular need of support because their work is expensive to produce while few private or public collections buy it or integrate it into their programming. She speculates that the technology required represents an added hurdle, especially for smaller institutions.

“You don’t see a lot of VR included in exhibitions or museum shows,” she said.

Meanwhile, the bank’s collection includes Jawa El Khash’s The Upper Side of the Sky, a 10-minute VR experience by the Toronto artist that produces a dreamscape or memory palace inspired by the ancient city of Palmyra, the archeological site that was heavily damaged by ISIS during the civil war in her native Syria.

Digital rather than physical art might seem ideally suited to viewing during the pandemic, but in truth exhibition of this art can be tricky precisely because the work is infinitely reproduceable. The bank acquires rights to screen the work in its offices, but does not usually own it outright.

“We aren’t printing these images; we aren’t sharing original files,” Linde said. “We are trying to fight for the value of this art. It’s very different: What does it mean to have a digital art work? What can you do with it? … It’s less about ownership than stewardship.”

Still, with staff mainly working from home, the bank has gotten creative about how to make the work accessible. Linde organized an Instagram exhibition for some of the artists early in the pandemic and there are now plans to commission screen savers and meeting backdrops for staff. Meanwhile, when the bank moves to new offices in 2023, digital art will be incorporated into the interior design.

Digital art can work well in a corporate setting, Linde said, pointing to the experience with PAN/PAN.

“There’s no audio. It’s under four minutes, and it’s really curious. A lot of people stop and say: ‘Wow, what am I looking at.’”

Find out what’s new on Canadian stages from Globe theatre critic J. Kelly Nestruck in the weekly Nestruck on Theatre newsletter. Sign up today.

Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor