Jamie Kastner, director of There Are No Fakes.david leyes/Courtesy of Cave 7 Productions Inc.

In spite of my current legal battle with the Ontario Provincial Police, I must admit visiting their headquarters in Orillia last week was pretty darn thrilling.

Beyond the vintage police boat in the lobby and the stuffed police dog in the souvenir store, it was exciting to see, splayed across the stage of their in-house theatre, all colour-printed and custom-mounted, a cross-section of the species of fraudulent Norval Morrisseau paintings at the heart of my 2019 TVO documentary There Are No Fakes.

There they were, not – for a refreshing change – pretending to be real Morrisseaus in some provincial gallery or at the CNE, or as dodgy little thumbnails online, but in a gleaming cop shop as part of a good news announcement of a seizure of 1,000 paintings, eight arrests and 40 charges against key members of the veritable fraud industry that has been manufacturing and trading in fake Morrisseaus since the mid-’90s.

Norval Morrisseau is of course the Anishinaabe art titan dubbed the “Picasso of the North,” who, before his death in 2007, founded the so-called Woodland School of pictograph-inspired art, was the first Indigenous artist to receive major commercial gallery shows in Canada, had his work shown as far and wide as the Pompidou Centre in Paris, and was the only Indigenous artist to receive a solo retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada. He was also the inspiration for a vast body of fakes that police investigators are now characterizing, at an estimated 4,500 to 6,000 paintings, as “the biggest art fraud in the world.”

Woodland art market took a hit over forgery rumours. Can it recover after a police crackdown?

The arrest list reads like an excerpted cast list of my film, and it was undoubtedly a moment of pride for me when, at the news conference, lead investigator Sergeant Jason Ryback of the Thunder Bay Police (the investigation was a joint effort by the two forces) acknowledged that watching There Are No Fakes inspired him to launch the investigation.

It’s not unusual for a documentary filmmaker to spend years trying to shed light on injustice. In my case, this was aided by years of prior digging by others to expose a story that went far beyond art fraud into myriad abuses of Indigenous people on individual, cultural, institutional and systemic levels.

But how incredibly rare to actually see that work achieving quantifiable real-world results. It was thrilling, with vaguely surreal overtones of having stuck a pin into a voodoo doll, then seeing its real life counterpart arrested.

And it was oddly gratifying to get backslaps and handshakes from a string of officers from the OPP theatre to the parking lot saying they’d all watched There Are No Fakes and how it had helped guide their investigation.

Which is part of why I have such mixed feelings about having to lawyer up to resist the very same officers, who asked me – nicely at first, then again backed by a court-issued production order – to surrender all the raw footage of the 17 interviews in There Are No Fakes.

The film tells the story, in part, of two warring factions at each other’s throats over the authenticity of a particular tranche of Morrisseau’s work (at the time, the estimate was some 3,000 paintings worth roughly $30-million). One faction – the fraudsters, let’s call them – shamelessly argue against Morrisseau’s own reasoning when he tried to call out the fakes during his lifetime.

A key part of my job is convincing people that talking on camera, in spite of the risks, will lead to a fair, respectful presentation in the context of a feature-length film. It takes some doing, believe me.

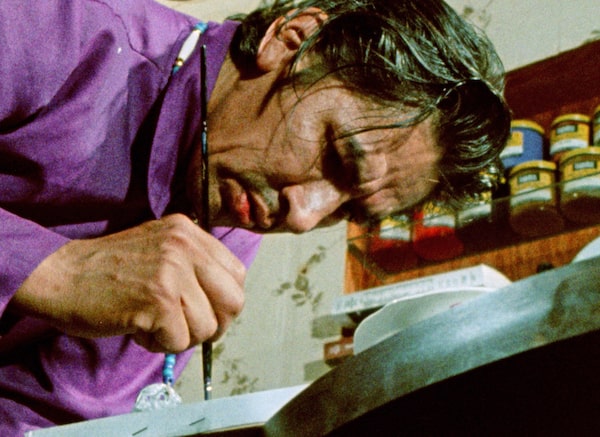

Norval Morrisseau, pictured in the 1970s from a National Film Board production.National Film Board of Canada / Cave 7 Productions Inc.

This film includes interviews with art dealers and auctioneers, some of whom arrogantly assumed they could handle talking to me without exposing their advertent or inadvertent role, emboldened perhaps by the assumption that the people further down the art production line – more vulnerable, often recovering addicts who’d actually held the brushes – would never contradict them.

They were wrong. The brave people below spoke up, and the misdeeds and prejudices of some of the higher-ups was revealed.

Would any of these people ever have spoken to me if I’d said I’d be turning the footage over to the cops? Safe to say no.

Now, a production order is seeking to compel me to betray my agreement with all these people, including some who detail personal abuses, which, even with the most careful and respectful editing, remain shocking. It would betray a trust fundamental to my profession.

The officers say the Crown needs the footage to make the charges stick.

At the police news conference, the investigators cited impressive numbers – they’d spent two and a half years deploying 98 officers over multiple jurisdictions countrywide to compile 271 statements, and seize 17 terabytes of data. In short, the police have conducted considerably more interviews than my little crack four-person filmmaking team did, including conducting their own interviews with the majority of the people interviewed in Fakes.

I sincerely applaud the officers for accomplishing what no prior law enforcement entity has managed to do since this story first began getting mainstream headlines in 2000. But having established they have ample budget, resources and skills to do their job, they should leave filmmakers and journalists to do ours.

I’m certainly not unhappy, though, when our work can complement one another’s, exposing injustice and bringing the perpetrators to justice respectively. But for the happy accident of such allegiances to continue, they must remain just that: accidents.

I’m told by our lawyer, Iain MacKinnon, that while the standard for police and Crowns getting production orders issued is pretty low – they simply need to show that the filmed material affords evidence of the commission of a crime – challenging the orders is an uphill battle. The onus is typically on the Crown to show the police have no other avenue to obtain the information. The OPP news conference clearly showed that’s not the case. But MacKinnon says courts typically favour the Crown in such cases regardless.

The issue at stake seems plain to me and to the film’s broadcasters and funders who are supporting fighting the production order. Leaving aside larger arguments about the sanctity of the fourth estate as watchdogs of democracy, it’s simple math:

If people believe that talking to documentary filmmakers and other journalists is equivalent to talking to cops, they may stop talking. Which could mean no more films, leading to no more investigations, leading to no more arrests, charges and seizures.

Maybe I should’ve bought that stuffed police dog in Orillia last week after all.