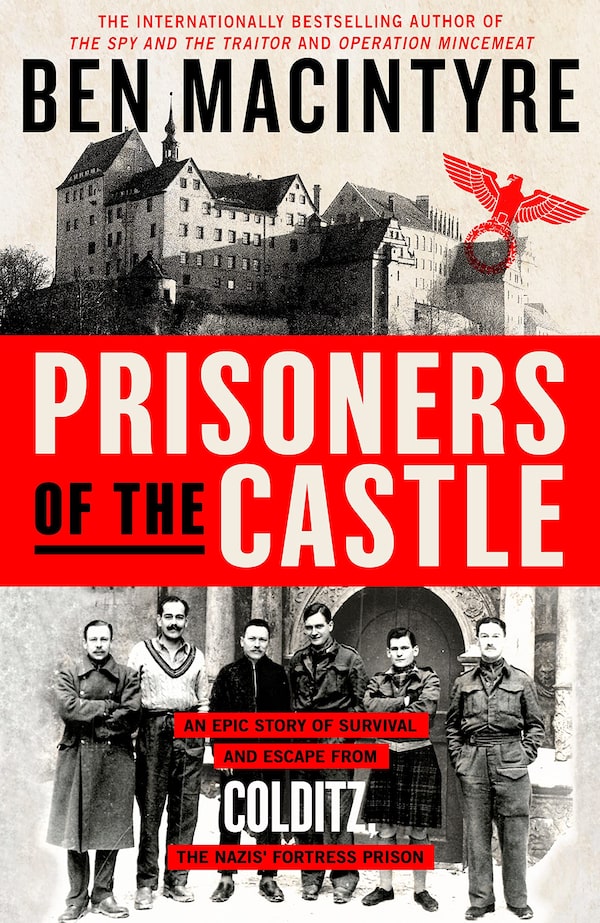

Colditz was a notorious wartime castle-cum-prison for high-risk POWs.Staatliche Schlosser Burgen und Garten Sachsen gGmbH Schloss Colditz

After writing more than a dozen critically lauded popular histories, many of them about espionage during the Second World War or the Cold War, Ben MacIntyre is enjoying a bit of a red-carpet moment: This year sees three major screen adaptations of the London Times columnist’s books. The film Operation Mincemeat, starring Colin Firth and Matthew Macfadyen, recently launched on Netflix, while two dramatic series – SAS Rogue Heroes and A Spy Among Friends, starring Damian Lewis and Guy Pearce – debut back-to-back at the end of October in Britain.

During a recent stop in Toronto to attend the International Festival of Authors, MacIntyre talked to Emily Donaldson about his latest book, Prisoners of the Castle, a novelistic account of life – the personalities, alliances, ceaselessly inventive escape attempts and occasional tragedies – at Colditz, Germany’s notorious wartime castle-cum-prison for high-risk POWs.

You’ve written about many war-related subjects. Why Colditz?

I grew up in the 1970s playing the Colditz board game, watching the BBC-TV series based on the books by Pat Reid, the great architect of the Colditz myth. Something like a third of the British population watched that series, so it’s deeply embedded into our national mythology. But I always knew Colditz couldn’t be just a story about brave British chaps trying to gather enough rope to climb off the chapel roof. Life isn’t that simple.

The Second World War was a literate war in the sense that everybody wrote everything down. I’ve lost count of the number of times I went to the family of somebody who was in Colditz and said, “Do you have any material?” Frequently people say, “Oh yes, there’s something in the attic, a box Grandpa left behind.” For me that’s absolute catnip, and that’s where a lot of the material from this story came from. Those stories are often very different from the accepted mythology, so I found I was writing a book, to my intense surprise, that was less about war – indeed less about masculine warfare – than it was about class and race and sexuality and mental illness and all the things we know human beings are prey to.

You went multiple times to Colditz for research. What’s it like now?

Weirdly, part of Colditz is now a youth hostel, so I spent part of my summer holiday two years ago living in this grim gothic castle on the banks of the Mulde. There’s an amazing archive and a very helpful local historian-archivist, and we had the most wonderful time digging down in the tunnels. As they renovate the castle, which they’re doing at the moment, they keep finding more escape equipment hidden in the walls and ceilings and floorboards, so in a way history is still unfolding in Colditz. It looks very forbidding in the wartime photographs. It’s this great Dracula’s schloss, but they’ve painted it white and it’s rather beautiful. There’s a sort of fairy tale element to it.

Author Ben Macintyre.Justine Stoddart/Handout

You’ve said previously that war can give opportunities to people with unusual minds. Who do think had the most unusual mind at Colditz?

There was this character, Micky Burn, who went on to become a correspondent for the Times. He was a feckless, rich, overeducated, lazy, intelligent sort of wandering figure. He’d battened onto fascism and ended up going to the Nuremberg rallies. Hitler gave him a copy of Mein Kampf, which he immediately lost in a taxi. But then he did a complete 180 and became a properly committed communist. To make up for his early dabbling with fascism he signed up for the commandos and took part in this incredibly brave and horrendous assault. He was captured and brought to Colditz. He looks at it with a very cynical and funny eye – he wrote the only good novel to come out of it. He was bisexual, completely open, so he writes about sex in Colditz in a way that nobody else does. I just loved his combination of dilettantism and intelligence and self-mockery. He ended up running a mussel farm collective off the coast of Wales. He was potty, but a wonderful observer.

One of the most surprisingly empathetic characters is the prison’s security officer, Reinhold Eggers.

That was a total surprise to me. I had inherited the idea that this was a brutal camp run by horrendous Nazis who were either very stupid or completely sadistic. But Colditz wasn’t a death camp. It wasn’t a place of routine brutality. It was a place run by the German army based on well-established rules that everybody knew. The Germans themselves were very punctilious and took deep offence at any suggestion that they were somehow bending the civilized rules of behaviour. Of course, as the war progressed, it became more brutal and appalling and those levels of understanding began to fray.

Eggers was reminiscent of schoolmasters, that sighing, finger-wagging kind. But in some ways he was the most humane figure, and, as you say, a sort of historian. I felt a community of spirit with him. I loved that he was gathering material because he knew this was important. Every time there was an escape attempt, or when he confiscated more contraband, he would add it to the stock of knowledge. Without him I don’t think I’d have been able to write this book. He’s the hidden narrator in some ways.

I didn’t put this in the book, but after the war he systematically tried to contact all the prisoners he’d known from Colditz. Not to apologize, not to make recompense, but to share a combined experience. I found all these wonderful letters he wrote to say, “Tell me what it was like for you, this is what it was like for me.”

Handout

That the prisoners maintained their class divides and social hierarchies so rigorously and willingly is sort of astonishing. Do you think this helped them psychologically?

I think it did to some extent. They imported and exaggerated the kind of clubby mentality and public-school ethos they brought with them. I think it made them feel that home wasn’t so far away. On the other hand – and this is again a good example of our modern sensibility looking into the past – I’m still appalled by the idea that one class of prisoner was allowed to seek their liberty and another class was effectively prevented from doing so. That seemed to me immoral: the idea that the masters, as it were, were considered of greater human value than the servants.

Assuming you didn’t have the entire run of the place, what perspective did you get on what the prisoners endured?

Actually I more or less did have the run of the place. It’s a place full of ghosts; not just wartime ghosts but prewar ghosts. This had been a place to incarcerate people who didn’t want to be there, from the unwanted children of the great electors of Saxony to troublesome siblings to unmarried daughters. It was a concentration camp, it was a lunatic asylum, and it’s impossible not to feel the accreted weight of some of that history. I don’t want to be too romantic about it, but I felt very conscious of the different lives that have been lived in a very enclosed space. It’s a difficult place to get into and a difficult place to get out of and you sense that even today. There’s something both magical and forbidding about it.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.