People visit the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican on the day of its reopening, after weeks of closure during COVID-19 restrictions, May 3, 2021.REMO CASILLI/Reuters

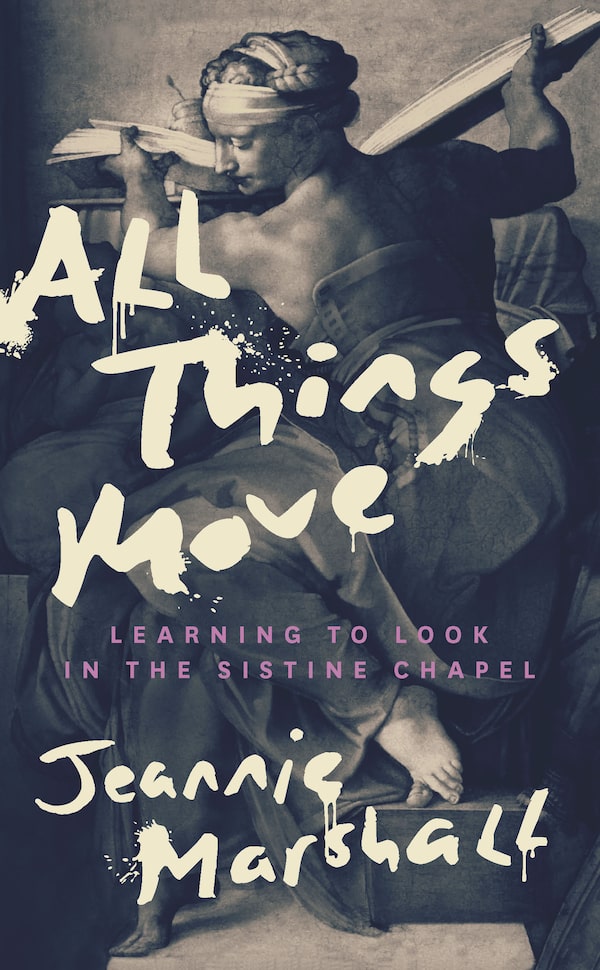

Jeannie Marshall moved to Rome in 2002, but for years never set foot in that too obvious mecca, the Sistine Chapel. Her conflicted feelings about religious art were one reason. But the experience itself is also notoriously exasperating. After enduring long lines, visitors must keep a brisk pace as they shuffle through the Chapel’s crammed space, necks craned skyward like a mob of meerkats. Any talk risks reprimand by the Chapel’s omnipresent “shushers.”

Her first visit to the Chapel would turn into one in a long series undertaken over several years. Marshall’s motives for doing this initially felt opaque to her. For a while, she didn’t even mention them to her family. How to find a way into this touchstone of Western art that struck her as at once “unknowable and too familiar?”

After reading the art critic Robert Hughes, she decided to approach the frescoes in the spirit of open contemplation. To pretend that she’d never seen God creating Adam on any number of coasters, throw pillows or bathroom walls. She made herself dwell on the less obvious places: Sibyls, pendentives, the hundreds of toes Michelangelo painted.

Handout

All Things Move (Biblioasis, 240 pages) is an account of those visits and that process, one made all the better for the fact that Marshall is not an art critic. Her aim – appropriate to the spirit of Renaissance humanism that inspired the frescoes – becomes one of pulling out the human stories beneath their biblical veneer, and her observations on this front are often disarmingly simple, lovely and intelligent. In learning about their historical context, she finds surprising points of continuity with the present.

Her book feels most urgent when, about halfway in, she begins to connect her experience with the frescoes to her impoverished Catholic upbringing around rural Lake Simcoe. The church had a directly negative impact on Marshall’s extended family, but particularly on her mother, Mary, as a result of its strictures against birth control and divorce.

It was a childhood where violence never felt far away. To the degree that when Marshall spies the still-visible gash marks left by a mob – infuriated by the church’s decadence – on Michelangelo’s panels during the 1527 sacking of Rome, it conjures a familiar sense of rage inspired by injustice and exclusion. (She compares the impetus for the attacks with one made centuries later on the work of abstract artist Barnett Newman.)

She feels the same undercurrent of violence on her daily travels around the streets of Rome, where fascist and antifascist graffiti sit alongside remnants of the Inquisition that sought to quash perceived threats to the church’s hegemony. In the Campo de’Fiori, where Marshall buys fruit, stands the pigeon-swarmed statue of Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake in 1600 for questioning, among other things, whether communion wine could literally be transformed into the blood of Christ.

In all this violence and beauty, and even in the religion to which she no longer adheres, Marshall discovers universality – an almost verboten term these days – and even a kind of hope. “The Sistine Chapel comes from a world before us with our twenty-first-century preoccupations,” she writes, “where we don’t really believe that art can do anything to us, but we come to see it anyway, just in case.”

Handout

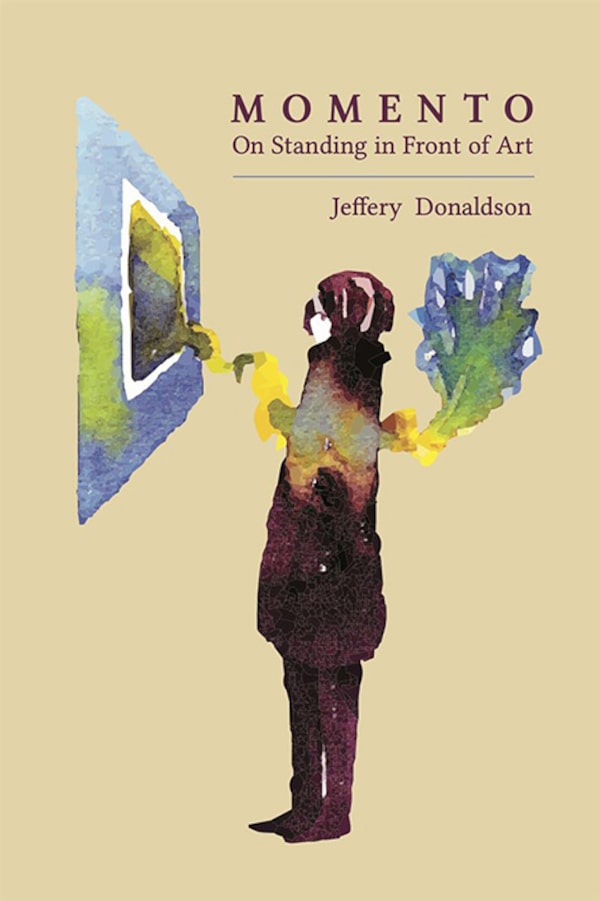

In his book Momento (Gordon Hill Press, 170 pages), Jeffery Donaldson shares with Jeannie Marshall a desire to bring fresh eyes to old art through open-minded inquiry. The references to movement in their titles seem to echo each other as well. Donaldson describes “momento” – a portmanteau of “memento” and “momentum” – as an attempt to “pull up what moves so that you can hold it.”

The difference is that Donaldson is interested not in a single work, but in the act of visiting a gallery itself. Many of us like to see art. But why? What do we expect from the experience? What draws one person to an ancient bronze bowl, another to a pointillist portrait?

This charmingly unpretentious book shows why such obvious questions might be worth asking. “The moment you feel that an object, in a sense, is more than what you thought, it approaches the condition of art,” is as a good a definition of art as I’ve come across.

Through a series of brief (one- to three-page) entries, Momento offers a kind of anatomy of a gallery visit. Donaldson brings his sensibilities as a poet, scholar and metaphor specialist nicely to bear as he probes the way we act and think around art. At other times, he’ll drill down into an artistic genre (annunciation paintings, say, or memento mori), or a single painting (Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Over the Sea of Fog), or an institution (the Art Gallery of Hamilton, the Tate in London).

Any museum- or gallerygoer will be familiar with the unique heaviness and lethargy those institutions induce (though it’s neither of these things, Marshall had this feeling in the Sistine Chapel too). Donaldson pins this weariness to the self-pressure of expectation and revelation. Art on walls is usually static, so it falls on us not just to behold it, but to make something of that beholding. It’s work.

Because it seeks to mimic a museum visit, Momento ends, naturally, in that airlock between the museum and the real world: the gift shop. The place where we can finally shed our art-looker’s detached cool and – museums being filled with things that aren’t for sale – re-engage our consumerist impulses. By picking up a poster of a work we admired, perhaps. Or a book about visiting museums.

Handout

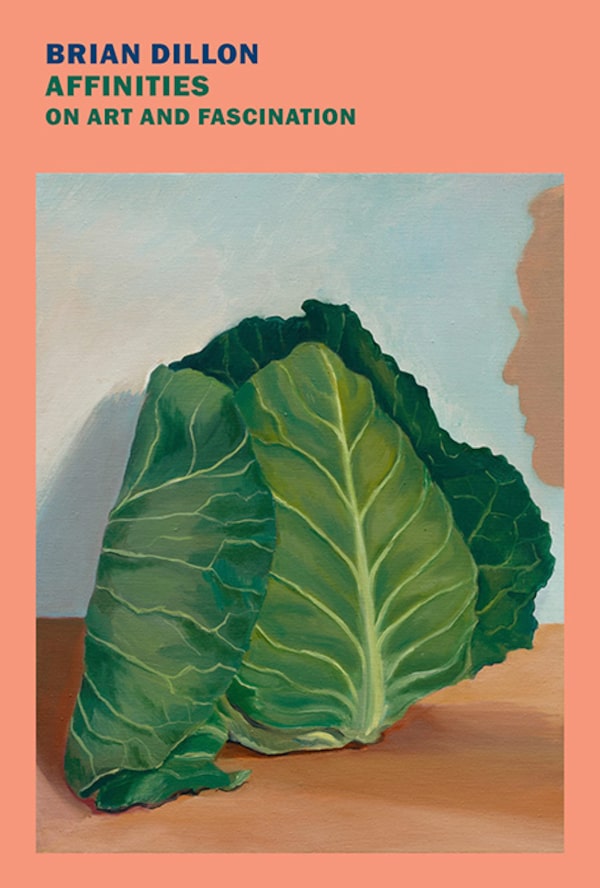

The way images can take hold of the mind is the focus of Brian Dillon’s Affinities: On Art and Fascination (New York Review Books, 320 pages), a collection of writings about the art and artifacts that have been kicking around in the Irish essayist’s mind “for years.” He intersperses these pieces, many of which read like distilled artist biographies, with a series of essays on the notion of “affinity” itself.

Dillon’s own affinities – at least the ones he writes about here – lean strongly early 20th century and modernist. He’s drawn to photography, as well as to the abstract, surreal and eccentric. Art created by women is strongly present in his book, including the collages of the German Dadaist Hannah Höch, the gender-bending photo self-portraits of French-Jewish artist/writer Claude Cahun, the fabric-enhanced choreography of American dancer Loie Fuller and the photomontages of Dora Maar (a practice she would abandon at the behest of her lover, Picasso, who then abandoned her for someone else.)

As sparkling as these profiles are, the standout piece for me is the one about Dillon’s late aunt Vera, a “vulgar fantasist” who became so obsessed that her neighbours might be trespassing on her property that she spent her final years paranoidly staring at video feeds of her flower beds.

Dillon barely tolerated Vera during her lifetime, so it feels poignant when he shifts gear, explaining that he now finds in her cranky agoraphobia, if not quite empathy, then a kind of weary recognition. “It’s the family curse, you might say, this turning from the world and peering at nothing or next to nothing until it gives something up, some objective correlative. We’ve all done it; it’s how we pass the time: we’re quite as mad as she was. I spend my days staring at the screen and hoping something will appear. I call it work, and she called it – what? The way things were.”

It’s a point that Marshall and Donaldson seem to make as well; namely, that we don’t choose our affinities, they choose us.