On the surface, Seconds Out: Women and Fighting by Vancouver-based Alison Dean and Nightbitch by American Rachel Yoder seem like very disparate books. The first combines a thoughtful analysis of women in fighting sports with a memoir of Dean’s own experiences as a dedicated kickboxer. The second is a dark, surreal and ultimately comic novel about a young mother who believes she is turning into a dog. What connects these debut works is frustration with self-imposed limitations and a desire to find a wilder and more authentic way of living (even if that search brings with it a lot of pain). Nathan Whitlock spoke to both authors about the limits of the intellect and the calming effects of violence – real and imagined.

Seconds Out: Women and Fighting combines a thoughtful analysis of women in fighting sports with a memoir of Dean’s own experiences as a dedicated kickboxerHandout

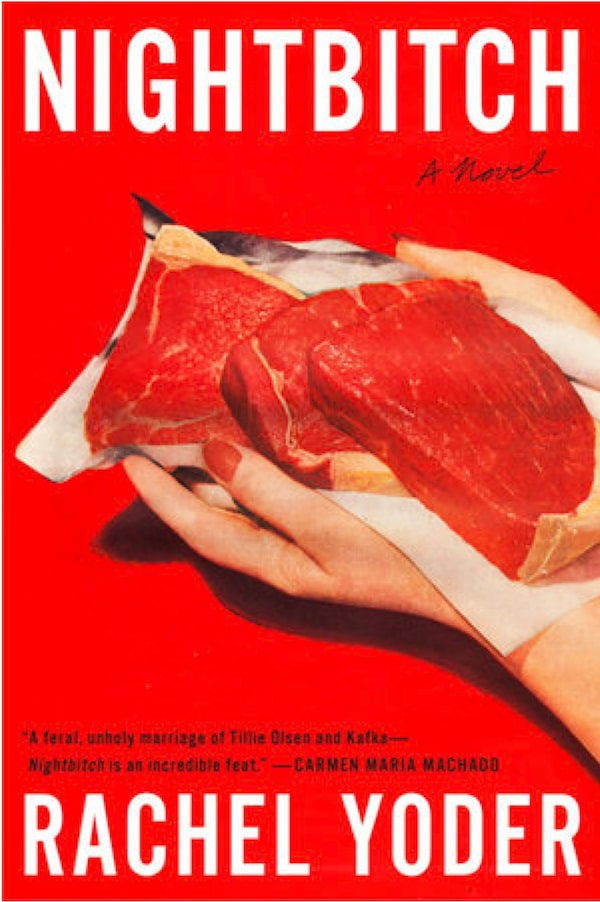

NW: Both of your books are very visceral. Rachel, yours has actual meat on the cover. And Alison, yours is full of punching and hitting and training and sweating. Is it especially weird to be discussing books like that when we’re still mostly staying distant?

AD: My plan had been to travel to different gyms and be really embedded in different lives and fighting styles and write about it, but because I was writing during COVID, I was completely isolated and trying to train by myself. A lot of the things that I really love about training are interpersonal, and they’re about that intimacy and interaction. It taught me different things about my subject matter and about my relationship to it, because so much got stripped away and it really came down to just what I could do and my own mental state. The way I wrote about the subject would be very different if I had been in contact with people and getting hit in the face regularly.

RY: There’s this profound isolation and loneliness at the heart of Nightbitch, so somehow there’s been a sort of poetic symmetry to talking about it to everyone in their own little squares on Zoom. It’s not what I would have wished, but I think perhaps people are connecting more with the loneliness and isolation of the book.

NW: I’m curious about the origins of the story. Was this a nightmare you had, or is it based on the feelings you had as a new mom?

RY: It was actually a joke my husband tossed off after I had had a particularly grumpy night. I was a stay-at-home mom and hadn’t slept in two years and got very perturbed when woken up in the middle of the night, and the next morning he’s like: “You were kind of a nightbitch last night.” And I was like, “Interesting idea, husband.” I’ve always really loved artists like John Waters who make things that are in poor taste but wind up turning out great. So there was definitely a sort of rebellious adolescent spirit I brought to this book. “I’m just gonna write a book with a non-marketable title with a ridiculous premise and I’m going to make it work.”

NW: There’s a memoir about becoming a parent that I love called A Life’s Work by Rachel Cusk. The vision of motherhood in it is nightmarish, and yet it’s got such a bland title, and usually the cover art is, like, a baby bottle or some baby shoes. I love that you leaned into the horror of it.

RY: I think motherhood is incredibly metal. Like birth itself: having your stomach cut open for a C-section or having a baby pulled out of you. It’s not bottles and soft blankies.

NW: Alison, you’re an academic and a teacher, you have your PhD – would you have imagined your first book would start with you literally demanding to be punched in the face by a sparring partner?

AD: It wasn’t what I planned. Fighting was supposed to be my hobby. I just got really intense about it and it kept growing and growing and taking up more space. I think after being so sedentary and disconnected from my body, I craved something physical. Fighting gave me the ability to to sort through things in a really satisfying physical way.

NW: This may be a comment on me more than anything, but my wife – who presents as very sweet – did a kickboxing class a couple of years ago and was told to settle down by the instructor. Like: “You’re hitting people way too hard! You’re getting way too into this!”

AD: You’re dealing with emotions you can’t intellectualize. I wouldn’t even know I was upset until I started hitting something. People were like: “You must be really angry, because you’re hitting that really hard!” But it’s like a chicken-and-egg: I might be angry so I hit it hard; or I hit it really hard, and that keeps me from getting angry. It became a calming influence.

RY: My narrator turns toward nature and toward wilderness as a location where she is able to perform power and perform chaos, because the domestic sphere isn’t an appropriate setting for her to express certain emotions. There are many images in our in culture of the “wild woman,” the unfettered woman, the violent woman, and I thought to myself: What’s so dangerous about those images? Maybe there’s something that’s actually really profound about those images. We get a lot of neutered domesticated images when it comes to motherhood, so what happens when we go out into the chaos, out into the wilderness, and into the anger? I was convinced there was some opportunity there and I wanted to find out what it was with the book.

NW: I want to do a bit of a switcheroo and ask you both to inhabit the world of the other’s book. Alison, I won’t ask if you’ve ever wanted to become a dog, but have you fantasized about going wild like that in your own way – like, showing up outside a bar at 3 a.m. and throwing punches?

AD: Never with strangers. What I like about about fighting in this kind of setting is that it’s consensual. I’m still trying to unleash something that I’m holding back. This is something that I’m actively working on with my coaches: They want me to be meaner. Because I do hold back even now. So there is a level of freedom and chaos that I would like to reach. I’ve been building up technique and control, but the next level is letting go. It sounds counterintuitive, but that’s what I’m working toward – letting go of that control to some extent because I feel like the fact that I haven’t been able to tap into that is a limitation for me.

Rachel Yoder's Nightbitch is a dark, surreal and ultimately comic novel about a young mother who believes she is turning into a dogHandout

NW: And Rachel, have you ever fantasized about spending a few hours punching or kicking or getting hit in the face?

RY: Honestly, I have never fantasized about that, but one fantasy I did have – which is also in the book – is when I was stuck at home, just me and my son. He was horrible at going to sleep, so I would just lay there in bed for hours, and what I would fantasize about was punching through the plaster in the bedroom wall – like, demolishing the entire room. Obviously it was expressing my frustration, but also it would have felt so good to get all of that frustration out of my body.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.