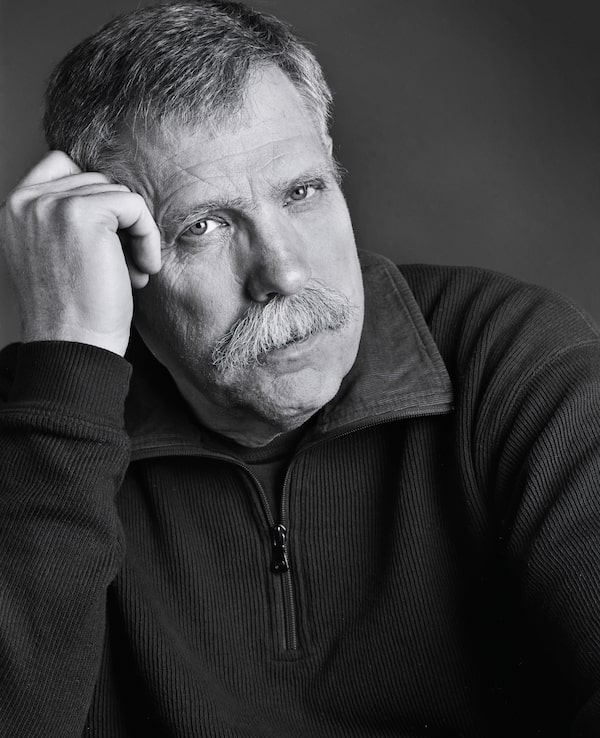

Ted Blodgett.Yukiko Onley/handout

Poetic inspiration could strike Ted Blodgett at any time. While he was sitting at a concert, for instance, or in the bathtub. He would then have to get up and immediately find some paper and pencil to write down the verses demanding to be born.

Even in the last months of his life, stricken with cancer, he wrote a poem a day, according to his wife, Irena Blodgett. “There was an inexhaustible reservoir of poetry in him,” she recalled. “The inspiration never failed. The words poured out.” His first book of poems, Take Away the Names, was published in 1975 by Coach House Press in Toronto, and thereafter his poetry collections appeared at regular intervals. He won the Governor-General’s poetry award in 1996 for Apostrophes: Woman at the Piano, and again in the translation category in 1998 for Transfiguration, the latter co-authored with Jacques Brault.

In all, he wrote close to 30 books of poetry, as well as dozens of literary essays.

Prof. Blodgett was in addition a medievalist and a beloved professor of comparative literature at the University of Alberta in Edmonton for almost four decades, where he encouraged his students to read foreign authors, whenever possible, in the original languages. He spoke French and German and could read Greek, Latin, Old Provençal, Old French, Middle High German, Dutch and Italian. The flag of the university flew at half-mast for five days to mark his passing after his death in a long term care home on Nov. 15 in Surrey, B.C., of malignant melanoma. He was 83.

According to his editor Peter Midgley at the University of Alberta Press, another book of his poetry will be published posthumously in early 2019.

“He was conversant with multiple languages and took your breath away with the depth of his reading and knowledge – everything from Virgil to German or Dutch poetry,” Mr. Midgley said. He credits Prof. Blodgett with encouraging “a conversation among languages” and an increased awareness of what poets are doing in Quebec, and in other countries. One of his books, Praha (2011), a sort of love letter to Prague, where Irena was from, is a dual-language edition that captures moments of being in that ancient city; the left-hand pages are in English and the right, in Czech translation.

Perhaps his most concrete legacy is to be found in Louise McKinney Riverfront Park in Edmonton. After he retired from teaching, Prof. Blodgett was Poet Laureate of the city from 2007 to 09 and in that capacity wrote Poems for a Small Park, describing how the trees, the birds, the river running through it change with the seasons. The poems – some of them translated into French, Chinese, Ukrainian and Indigenous languages – have been engraved on steel straps wrapped around the lamp posts along the river, a permanent part of the park’s design. For example:

and let us turn our heart

to old trees that through

the many winters of

their lives have reached forth

to greet the passing birds

and in their branches held

the winds that went astray

beneath the frozen moon

And solitary stars

Edward Dickinson Blodgett was born in Philadelphia on Feb. 26, 1935, one of three children of Grace (née Lindabury) and Edward Dickinson Blodgett, a radio engineer. His father tried to steer him toward the sciences, but it was his mother’s love of books that had the greater influence. Ted obtained his BA in English literature from Amherst College in Massachusetts, then a master’s degree in French at the University of Minnesota, before enrolling in the PhD program at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. Before he had finished his thesis in medieval studies, he began applying for a teaching job in his field. By then he was married to his first wife, the former Elke Krueger, who had come to the United States from postwar Germany, and had two children to support. In 1966, when the University of Alberta offered him a position as associate professor of comparative literature and Romance languages, the young scholar left the United States behind for Canada, a country he grew to greatly appreciate. He embraced its literary traditions as well as its hockey tradition, becoming a huge Oilers fan.

He and Elke welcomed a third child in Edmonton, but the marriage was unhappy and they divorced in the late 1980s. Elke Blodgett died earlier this year in St. Albert, Alta.

At the University of Alberta he taught everything from a popular long-running introductory course in world literature to a class in feminist literary theory. For more than two decades, he was a full professor of comparative literature, serving for a time as head of the department and as an editor of a journal of comparative literature. That is how, in 1991, he encountered Irena Krupickova, who worked on the journal in a secretarial capacity. She became his second wife; he leaves her, along with his three children, Gunnar, Astrid and Kirsten, and stepson Peter. He also leaves his sister Linda and eight grandchildren.

Over the years he supervised more than 20 PhD candidates. These former students, whom he kept in touch with, have fanned out across the globe and now teach in places ranging from Dalhousie and Ryerson University, to the American University in Lebanon.

One of his most authoritative critical essays was a 20-page summary of francophone literature in Canada from the 16th century to the present that appeared in The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature, edited by University of British Columbia professor Eva-Marie Kroller, whose doctoral work he had also supervised.

In 1986, he was named a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, After his retirement at 65 in 2000, he was appointed Distinguished University Professor of Comparative Literature, and taught for two years at Campus Saint-Jean, the francophone campus of the University of Alberta.

He made time, too, for building an arts community, founding the Writers Guild of Alberta with novelist Rudy Wiebe and acting as its president in 1981-83, chairing the Edmonton Arts Council, singing with the choral group the Richard Eaton Singers in Edmonton, and being named in 2011 to Edmonton’s Arts and Culture Hall of Fame.

A skilled player of the lute, he linked music and poetry in his work occasionally providing the text for choral works. Published earlier this year, his collection Songs for Dead Children borrowed its title from Gustav Mahler’s song cycle called, in German, Kindertotenlieder. According to his wife, he was deeply troubled by the suffering of children in the deadly conflicts of the modern world. In an untitled verse he imagines what it’s like:

never to grow old

to sit beside the sea

to gaze at the shape of clouds

to have a memory of things

simply to love the sun

never to know the past…

to gather the shadows

of long afternoons

When he and Irena retired to Surrey in 2009, he found a new lute teacher, Ray Nurse, and took the bus to Vancouver every two weeks for lessons. “It’s an obscure instrument, probably dating from Europe in the 12th century,” Mr. Nurse explained. “He had a fascination with historical things. He was probably the most eager, dedicated student I ever had. And he was an extraordinarily fun person to be around, with a superhuman kind of vigour and energy. He could practise [the lute] for hours, write a poem, and read two novels the same day.”