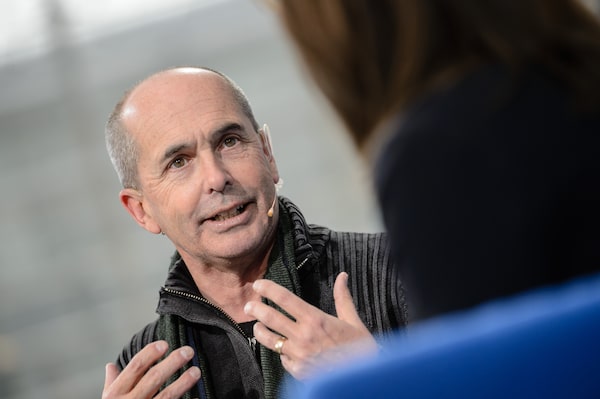

American author Don Winslow speaks at the Leipzig Book Fair on March 18, 2016 in Leipzig, Germany.Jens Schlueter/Getty Images

Crime novelist Don Winslow is used to the real world wriggling its way into his writing. His massive, three-book Art Keller trilogy capped itself off last year with The Border, in which Winslow’s heroic DEA agent faced off against a facsimile of Donald Trump and Jared Kushner. But the one time Winslow decided to, mostly, leave the real world behind, the real world decided to make its own plans.

Just as Winslow was readying his book tour for Broken, a collection of six new novellas that (again, mostly) favour California-cool escapism over gritty verisimilitude, the world went on lockdown. But never one to miss an opportunity to boost the business of independent booksellers and share his thoughts on how Trump manages crisis, Winslow has launched a “virtual tour” to do both.

Winslow spoke from his home north of San Diego – “It’s always quiet here, but it does feel different, and I can’t quite articulate how” – with The Globe and Mail’s Barry Hertz about his life of crime-writing.

This collection acts as a great diversion – it’s funny, thrilling and, yeah, occasionally horrific. But there’s a lot of escapism here.

The last 22 years of my career have been spent on longer-form fiction, these big, fat books, and I wanted to try this format: Stories that weren’t epics that spanned decades. These take place over days, at the longest.

How long have these stories been kicking around in your head?

It varies. The final story, The Last Ride, is topical, about kids at the border. So that demanded to be written. But the others have been kicking around in my head for a couple of years, when I didn’t have the space in my schedule to write them. The problem with life, or the life of a writer, is not that there aren’t enough stories to tell, just that there’s too many. Just like there are too many books to read.

The stories shift in tone and storytelling style quite significantly here. You open with the hard-hitting police thriller of the title, Broken,. Then we’re in the breezy heist territory of Crime 101, and then almost a rom-com with The San Diego Zoo. Were you worried about storytelling whiplash?

Absolutely, but that’s the fun. I’ve never wanted to be sort of pinned down to just writing in one voice or one topic, the drug trilogy notwithstanding. I think of my favourite jazz musicians, who can play hard pop and ballads. I’d never want to tell Charlie Parker, “Hey, you can only play that hard, fast driving stuff, but you can’t play Summertime or Lover Man.” Just like when Frank Lloyd Wright said that form follows function in architecture, I think that style follows story.

And you do make those stylistic distinctions right off the top, with each novella dedicated to a different artist: Elmore Leonard, Raymond Chandler.

I’m not hiding anything. Obviously Mr. Leonard was a major hero of mine. I never met him, but I had a one-hour phone conversation with him shortly before he passed, and that was a highlight of my life. And I was at Chandler’s house last year in San Diego, which was like going to church.

you famously draw on research and interviews – fact seems to be your guiding voice.

For a lot of it, yes. My job is to bring the reader into a world that he or she couldn’t get into, and for that, I need to get it right. There’s very little fiction in the drug books; every violent incident that happened in those books happened in one form or another in real life.

How does it affect you, in your life, going to those dark places as a researcher and author?

It has its effect, but I worry more about the effect it has on the reader. How do you accomplish getting that reality across without crossing the line into, if you will, the pornography of violence? You do see things and hear things that maybe you’d rather not have in an ideal world. But this isn’t an ideal world.

That real world is also where you’ve turned into something of an activist – you’re promoting your books, but also going on MSNBC’s Morning Joe to lay into Trump.

Primarily I’m a novelist, and what’s where I live. I never wanted to be a political person. But when you’ve been on this beat for as long as I have, I felt some responsibility to speak out when I had the opportunity. There’s a narrow window when a book comes out when more people are paying attention to you than other times, and I didn’t want to only be a voyeur to people’s suffering.

So now here’s the obvious question: How is Trump ...

Well, he’s messing this all up. He’s making the situation worse – serving himself instead of the people he swore to serve. I think he’s done a horrible, horrible job with the virus. But what would you expect?

Do you find yourself, maybe it’s inappropriate to ask this right now, but is there a sort of backward inspiration to be found from our current situation, for your work?

Not at all. I don't write about those topics ... but I cannot help but think of what the late Michael Crichton would've done with this. Stephen King to a certain extent, too. But it's just too close right now. I'm writing now, but certainly not about this.

This interview has been condensed and edited

Broken by Don Winslow is available April 7 from HarperCollins

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.

Barry Hertz

Barry Hertz