Author Charlotte Gray.Michelle Valberg./Handout

In 2003, when Charlotte Gray won the Pierre Berton Prize for “distinguished achievement in popularizing and promoting Canadian history,” with an ailing Berton in attendance (he died the following year), a certain passing of the torch seemed to be taking place.

Indeed, two decades on, Gray remains one of the few writers – along with Margaret MacMillan, Stephen Bown, Tim Cook and Mark Bourrie – regularly producing popular (that is, readable, non-memoir-based and non-academic) works of Canadian history.

Books we're reading and loving this week: Globe staffers and readers share their book picks

And though she’s flattered by the comparison between herself and Berton, and has strong praise for his work – ”He was a hell of a writer. If you read his history of the CPR now, the momentum is extraordinary” – she’s also aware of the differences. Berton could be, she says, “a little fast and loose with the facts.” And, unlike her, his interest was in writing “big, muscular, tub-thumping national epics.”

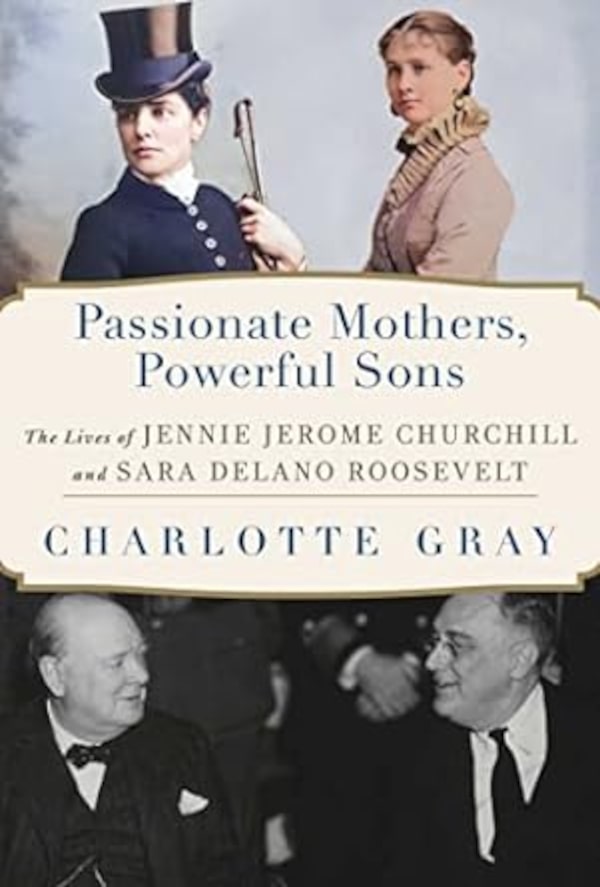

Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons by Charlotte Gray.Handout

Gray avoids the “big guys,” she said in a recent interview, “because they’re built on an infrastructure of supporters, ideas, people, wives, mothers. There’s a lot more to a great man of history than just his brilliant brain working out the issues.” Cue her newest book, Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons, which tweaks an old saw in its suggestion that behind every great man is a great mother. (Though maybe “influential” is better than “great;” and perhaps the rule applies only to very specific mothers, not all of them.)

The book is a double-helix biography of Jennie Jerome (Churchill) and Sara Delano (Roosevelt), mothers of Winston and Franklin, who came from uncannily similar origins. Both were born in 1854, into wealthy New York State families. Both lived in Paris at a similar time of their youth, were widowed early and would ultimately have a profound impact on the careers of their statesmen sons, who in turn adored them. The men themselves would eventually meet, of course. Their mothers apparently never did.

Even more interesting to Gray, given those similarities, were the women’s radically different personalities: Jennie was a spendthrift, modern, vivacious bonne vivante and networker extraordinaire. Sara a staunch, rather humourless keeper of conservative tradition per her strong Victorian mores and unassailable Mayflower pedigree. (Vying for the role of the third main female character in the book is Eleanor Roosevelt, whose fraught relationship with her mother-in-law is one of its most fascinating aspects.)

The mothers’ attitudes to their sons’ chosen profession nicely highlight their contrasting natures. Jennie found the political world exhilarating, throwing lavish parties in England, where she moved early in life, to help Winston achieve the career that her late husband, Lord Randolph Churchill, had squandered through poor decision-making. Sara, on the other hand, found politics boorish and distasteful, initially doing her level best to dissuade Franklin from sullying the family reputation by running for office. (His contracting of polio seemed like it might do the job for her. She was dismayed when it left him undeterred.)

One thing both women did share was contempt for the suffragette movement. Although their pro-suffrage sons did eventually win them over to the cause, both felt that true power lay in backrooms, not in the vote.

Gray, as ever, writes warmly and chattily, with a novelist’s ear. Her words do furnish a well-appointed Victorian-Edwardian room. In calm, sedate Hyde Park, estate of the Democratic, Hudson Valley Roosevelts (not to be confused with the Republican, Oyster Bay clan), for instance, we see quiet, bookish Franklin tending to his stamp collection. And, across the pond, Jennie treading the corridors of lavish Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, ancestral seat of the Churchills.

Gray’s own origins are far more humble. Born in 1948, she grew up in Sheffield, where her 19th-century forebears worked in the steel industry and where her father was the lawyer for the Sheffield United soccer team. (She describes her mother as a person who “quietly made a lot of very important decisions just by saying, ‘Yes dear,’ then doing what she wanted.”)

The city’s economic fortunes fell by the wayside between the Second World War and the Thatcher era (it’s since had something of a renaissance). By then, though, Gray’s parents had moved away. Gray herself was in the process of completing her education, which began in boarding school in the south of England, then took her to Oxford for an undergraduate degree in history followed by the London School of Economics for a graduate degree in social administration (“I still don’t know what that means”).

A Canadian boyfriend, met at Oxford, lured Gray to Ottawa in 1979. The plan was to stay for four years, then return to her “real” country.

But when that time was up, Gray had a brood of three (Canadian) boys. And the boyfriend, George Anderson, had morphed into a husband with a promising future in the Canadian public service. Gray herself had successfully parlayed the journalistic career she embarked on in London – where, among other gigs, she served as co-editor of the British version of Psychology Today – into that of columnist and political commentator, including for Saturday Night magazine.

And in truth, she was happy to stay. Compared with Britain, she found Canada appealingly heterogeneous and socially mobile. She appreciated that someone who’d owned a gas station and car dealership in Alberta could eventually become finance minister (Don Mazankowski), or that the son of a Filipino jeepney driver who had qualified as a physician could be elected to the federal Parliament from Winnipeg and become a champion of medicare and immigrants, not to mention a minister of Western economic diversification (Dr. Rey Pagtakhan).

When Gray’s husband became a deputy minister (a position he would hold in several departments), she switched to writing history and biography. The couple felt that too many people would assume a conflict of interest if she continued as a political columnist. “Though in fact,” she notes, “we never discussed his job or my articles. When you’re raising three active sons, such topics are low on the list of domestic priorities.”

Passionate Mothers interestingly combines approaches Gray took in earlier books. Her first was about Isabel Mackenzie King, mother of Canada’s longest serving prime minister, while Sisters in the Wilderness was a dual biography of Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill. (Other biographical subjects include the Mohawk poet and performer E. Pauline Johnson; suffragist Nellie McClung, and inventor Alexander Graham Bell.) In recent years, she’s also made forays into historical true crime with The Massey Murder and Murdered Midas.

She began her research for Passionate Mothers by delving into secondary sources, including the truckload of existing biographies about FDR and Churchill – Churchill alone has spawned an entire publishing industry, as well as a dedicated bookshop in New York. There were so many that one of Gray’s challenges was deciding when to stop reading them.

Jennie Churchill, she discovered, had generated a fair bit of ink from Churchill’s mostly male biographers, though much of it was disparaging and related to her legendarily numerous affairs, including with men half her age. (Lord Randolph’s own numerous dalliances seemed to generate less comment. Go figure.) Jennie’s many significant achievements, which included singlehandedly organizing and outfitting a hospital ship that sailed to South Africa during the Boer War, starting a literary journal, writing a book, as well as dabbling in theatre and real estate, were often glossed over or diminished.

Next would be Gray’s favourite part of the job: digging through archives, a process she loves for its intimacy. “Obviously, you know they’re dead – they’re not speaking to you – and yet they are speaking to you. You feel close to them in a way that you can’t when you’re reading stuff between hard covers selected by somebody else.”

She was gearing up to go to the Churchill and the Roosevelt archives (at Cambridge and Hyde Park respectively), when the pandemic hit, but she got there, despite the delay. Finally getting her hands on Jennie and Sara’s letters, she says, was “heaven.” The contrast between Jennie’s “cheerful scroll” and Sara’s controlled, precise penmanship seemed to confirm everything she’d learned about the two women.

Though Gray lived briefly in Japan and the U.S., Ottawa remains her only home in Canada. She still feels warmly about the place, calling it ideal for those like herself who want to write about politics, or want to meet people from every corner of the country.

Most of Gray’s other 11 books include non-Canadian elements, but Passionate Mothers is her first on a completely non-Canadian subject. This, she is adamant, does not mean she’s turning her back on Canadian history. On the contrary, the latter’s survival has become something of a preoccupation for Gray (far more so than where she stands in the post-Berton line of succession).

In August, she wrote an impassioned piece on the barriers to writing non-fiction in this country – financial ones being prime among them – in the pages of this paper, which she says is still eliciting concerned responses from readers and publishers. (Depressingly making her point, Passionate Mothers notes that, in 1906, long before he became prime minster, Winston Churchill received an advance equivalent to £800,000 in today’s money to write a biography of his father.)

Writing about Jennie Jerome and Sara Delano was, Gray says, about “wanting to tackle a bigger story, and about being interested in these women’s lives. Also about realizing that there was a market out there which my books weren’t reaching. I wanted to see if I could reach it, and it’s working quite well.” (The book is her first to be published in the U.S. and Britain.)

“Each of my books is the result of something niggling in my own mind, a curiosity, a question that I want answered,” she says. “In this particular case, the question was: How were these two women similar and how were they different, and what impact did they have on their sons? Okay, that’s actually three questions, but I’m bad at math.”