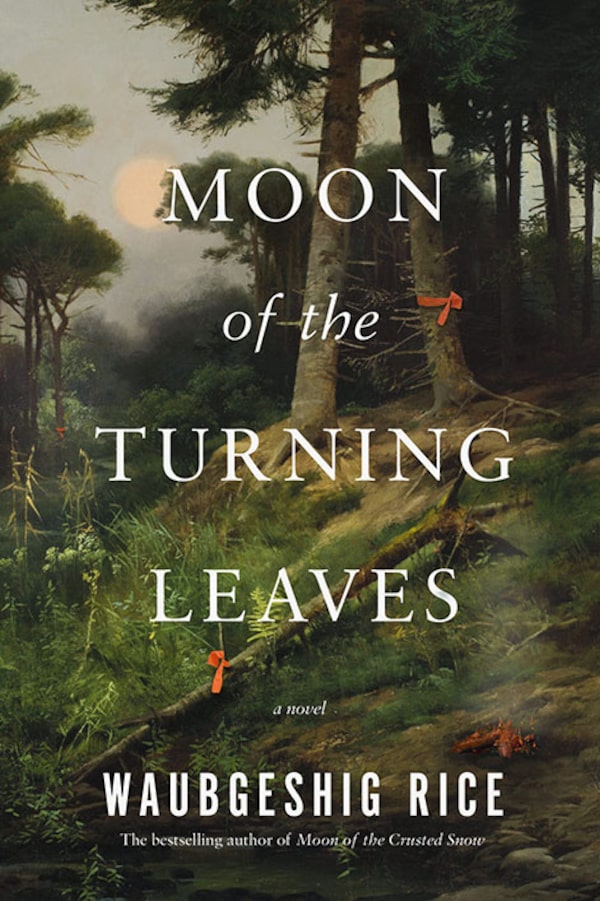

Anishinaabe journalist and author Waubgeshig Rice launches his latest novel, Moon of the Turning Leaves, this month. It is the sequel to his bestselling novel Moon of the Crusted Snow published in 2018.VANESSA TIGNANELLI/The Globe and Mail

Waubgeshig Rice was at his dad’s place on the Wasauksing First Nation when the power went out. But it was a bright, placid August afternoon in 2003, and at first, he and his two younger brothers didn’t think much of it. Eventually boredom spurred them to hop in the car and drive to the nearby town of Parry Sound, where an eerie sight lay before them. The street lights were out, the storefronts shadowy and silent. Stopping to talk to friends, they learned that the blackout stretched south to Toronto and beyond; millions of people were in the dark. “Right away, we thought it was the apocalypse,” Rice remembers. The brothers sped back to the rez, where they gathered firewood, checked in on their grandmother, and started making a survival plan.

Michael Lewis dives into the mind of Sam Bankman-Fried in his new book Going Infinite

“The more we thought about it, the more we were like, we don’t need power here,” said Rice, who was 24 at the time and freelancing as a journalist in Toronto, a three-hour drive south. “People here know how to hunt. They know how to fish, they know how to gather stuff from the bush. We’re going to be fine if we hang out here on the rez.” The next morning, as the brothers got ready to go fishing – the beginning of their new life at the end of the world, Rice jokes – the power came back on. The Northeast blackout of 2003, which affected more than 55 million people in Canada and the United States, was over as suddenly as it had started. But for Rice, a story had begun that would take another 15 years to tell.

Books we're reading and loving this week: Globe staffers and readers share their book picks

That story was Moon of the Crusted Snow, a slow-burning thriller that came out in 2018. His follow-up, Moon of the Turning Leaves, comes out this month, picking up where Crusted Snow left off.

Moon of the Turning Leaves, by Waubgeshig Rise.Handout

The first novel is about a remote Anishinaabe community grappling with an unexplained catastrophe: First their communications fail, then their power. Winter sets in. Two community members arrive from the south, fleeing an eruption of violence and chaos. Society collapsing in the wake of disaster is the well-worn premise of postapocalyptic novels from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road to Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven, but in Rice’s story, the centre holds. Rather than turn on one another, the community pulls together; after all, the apocalypse is an anticlimax that Indigenous people are uniquely prepared to endure.

“Our world isn’t ending. It already ended,” an elder tells Evan Whitesky, the young father and hunter at the heart of the story. “When the Zhaagnaash cut down all the trees and fished all the fish and forced us out of there, that’s when our world ended.” But history repeats itself: a white man arrives with promises of peace, expecting to be welcomed and protected by the Indigenous community even as he plans to plunder it for his own survival.

Snow was a sleeper hit, and Rice found himself fielding an unexpected question from readers: would he write a sequel? He could see how disappointed they were when he said no. “So I started massaging the truth a bit,” he admits over Zoom, basking in the afternoon sunlight outside his home in Sudbury, where he lives with his wife and three sons. “I’d say, ‘Oh, I’m thinking about it.’” That line worked on him too, and soon he was thinking about the story that would become Moon of the Turning Leaves, which will debut on October 10. In March, 2020, he signed a contract to publish it with Random House Canada. Then the real apocalypse arrived.

The pandemic prompted him to rethink his approach, including plot points that hewed uncomfortably close to reality. “I was like, man, no one’s going to want to read a novel with a plague,” he recalls. Instead, he found himself writing a book about resilience in the face of devastation. “Being able to confide in the story was really therapeutic for me,” he says, “because it allowed me to offer a more hopeful glimpse of the future for this world.”

Moon of the Turning Leaves is set 12 years later, in a new settlement founded by Evan Whitesky and the other surviving community members, who left their rez at the end of Snow. Their Anishinaabe language and practices have grown stronger, but food is becoming scarce, so Evan and his now-teenage daughter Nangohns join a scouting party and set out in search of their ancestral homelands to the south. Rice cites The Road as an influence, and if Snow evoked its portrait of a father reckoning with the apocalypse, Leaves borrows its perambulatory structure as the characters traverse a hostile landscape, tracking the faint hope of a future worth living for.

Now best known for his fiction, Rice spent more than 20 years as a journalist. His first gig was as a teenage correspondent for the Anishinabek News, writing monthly articles about his experience as an exchange student in Germany for Anishinaabe readers across Ontario. In 2006, he moved to Winnipeg for a job with CBC, landing in a newsroom with Indigenous journalists like Sheila North and Wab Kinew, a stroke of good fortune at a time when Indigenous reporters were even more under-represented than they are now. “We were able to form our own little rez in the newsroom,” he says, “And without that I would definitely not have lasted at CBC.”

In 2011, he published his first work of fiction, the slender story collection Midnight Sweatlodge, in which Indigenous characters chronicle their traumas in the search for healing, recounting tales of heartbreak, alcohol abuse, and police brutality. Rice, who drew inspiration from real events on his own reserve, said that publishing it solidified his belief in the power of fiction. “It’s a refuge for a lot of people, a tool of enlightenment for others, and a community builder for so many more.”

A novel, Legacy, followed in 2014, but it wasn’t until the publication of Moon of the Crusted Snow that Rice’s career as a novelist took off, enabling him to quit the CBC in 2020. In his fiction, Rice found he was able to portray the daily aspects of Indigenous life that never made it into his reporting. “I can tap into an individual’s daily smudging practice or the playful joshing they do with their loved ones,” he says. “That’s for other Indigenous people, first and foremost, to have something familiar on the page. Because it was a long time before I saw anything like that.”

There was no high school in Wasauksing, so Rice matriculated in Parry Sound, where his English curriculum focused on white male authors: W.O. Mitchell, J.D. Salinger, William Golding. The only Indigenous representation was a character in Farley Mowatt’s 1956 novel, Two Against the North. But Rice’s auntie, Elane Kelly, was a teacher, and she introduced him to Indigenous authors like Richard Wagamese and Lee Maracle. He was struck by Jordan Wheeler’s Brother in Arms and Richard Van Camp’s The Lesser Blessed, coming-of-age stories that depicted Indigenous youth in all their heartbreak and complexity. Though Rice emphasizes that the setting of his novels is “entirely fictional,” the details are true to Anishinaabe life. “The slang, the mannerisms, the social dynamics – everything is what I know from being raised in Wasauksing,” he says.

Interest in postapocalyptic fiction surged during the early months of COVID-19, and Snow rebounded onto bestseller lists, propelled by readers who embraced its prophetic vision of disaster. Leaves feels similarly well-timed to the current moment, as the worst-ever wildfire season in Canadian history rages on. Its characters are living in a depleting landscape, aware that the land can’t support them anymore and time is running out. “There needs to be a balance with all the life in the waters around us,” an Elder says, “And right now, we’re upsetting that balance.”

If Snow was Evan’s story, Leaves belongs to the Nangohns, and the novel is oriented toward the responsibilities we have to the next generation to fix the crisis before us. “We didn’t choose where we got to be born,” Nangohns tells her elders. “But we trusted you to care for us. To love us. To make the right decisions for us.” Rice’s first son was born as he was finishing Snow, and his third arrived in January. Becoming a father, he says, was a profound transformation that made it onto the page. “I have much more at stake now,” he says. “I have to raise these three kids in this world. And so in that sense, I can attach my own hopes and visions for the future to the story, and really instill them in the narrative itself.”

Like its predecessor, Leaves smoulders with mounting tension, punctuated by flashes of shocking violence. But from the opening scene – a joyous birth and traditional naming ceremony – Rice reminds the reader that regeneration can always follow disaster. “Putting that first and centring it was important,” he says “Not just for the story, but just for everybody to see.” After generations of birth evacuations, he tells me, babies are being born on Wasauksing again, delivered by Anishaanabe midwives whose knowledge and traditions have survived a cultural genocide.

A sequel prompts an inevitable question: will there be a third book? Rice is open to it, but first he wants to try writing something comedic for a change – a tribute, he says, to the resilience of Indigenous joy. “Despite all the traumas that so many Indigenous people have endured, they are able to smile and laugh, and make other people smile and laugh too,” he says. “That’s what I want to try to capture in the next novel that I write.”

In Leaves is another answer to that inevitable question: one world may end, but another is always possible, and in that possibility we can find refuge from disaster. The same, of course, is true of stories.