Memoir author Lauren Hough.KARL POSS IV/The New York Times News Service

We live in a time of two competing and profoundly different modes of discourse. One of them, literature, is a space for deep thinking on complex questions, but the ascendant medium, Twitter, is more interested in condemnation and moral outrage. When Twitter takes on literature, the results can be disastrous. Memoir author Lauren Hough experienced this firsthand when her book was withdrawn from the list of Lambda Literary Prize nominees for her involvement in a Twitter controversy.

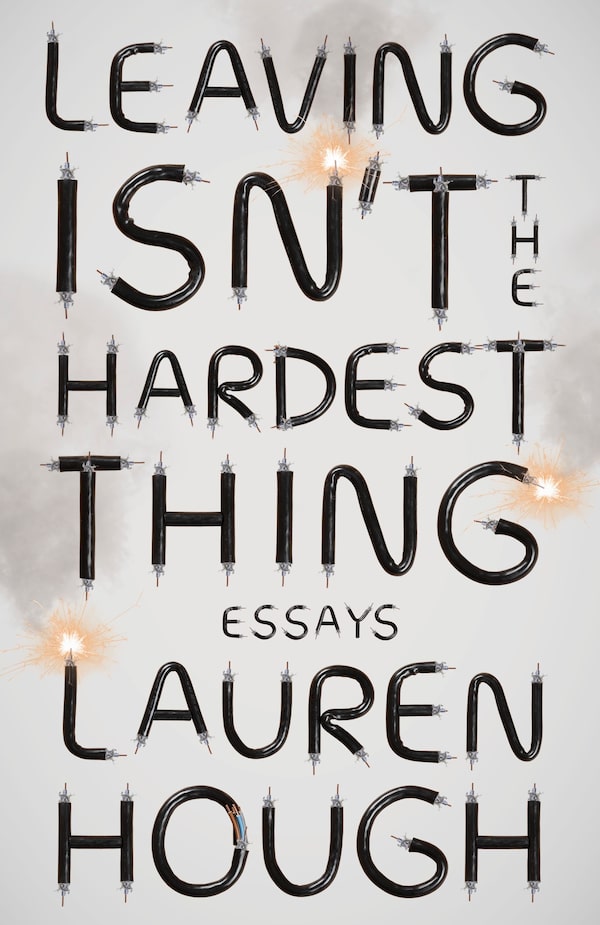

Hough is a writer who is caught between the world of literature and the world of Twitter. Her first book Leaving Isn’t the Hardest Thing received critical acclaim and spent two weeks on the New York Times best seller list. It was nominated for the Lambda Literary Prize for best lesbian memoir. These are huge accomplishments for any writer, but Hough’s story is a little different from that of many other celebrated authors who have achieved such success. Hough does not have an MFA in creative writing. According to her, she barely passed high school. She wrote Leaving on a work laptop in her work van, outside grocery stores and hardware stores. When it came time to seek a publisher, she did not have the money to hire anyone to help her or the connections afforded to writers who do MFA programs. All she had was her tenacity and the strength of her words. She sought out connections on Twitter, a place where, despite the ubiquitous hostility, writers congregate. She found a friend there, fellow writer Sandra Newman, and with Newman’s help, Hough was able to find a publisher.

After the release of Hough’s book, Newman’s forthcoming book, The Men, was announced. Hough was celebrating the reception of her memoir as the outrage machine that is Twitter caught wind of her friend’s book.

The Associated Press

While not an individual, or even an organized group of individuals, Twitter produces a specific mode of thinking and relating. When I write “Twitter,” I am not referring to the platform, but to the collective voice that emerges from it. In particular, the collective voice that emerges when this mode of relating is taken up in the fight for social justice. Individuals on Twitter who disagree with the thrust of this collective voice are discounted at best and actively harassed at worst, including those who occupy the marginalized identities that this collective voice claims to speak for.

The Men has not yet been released. All the same, the argument that the book is transphobic – because it apparently did not take trans people into account in its premise – took hold on Twitter. Hough came to her friend’s defence, and insisted that the Twitter mob back off. This resulted in Twitter turning on Hough, and accusing her of being a TERF (trans-exclusionary radical feminist) for defending her friend’s forthcoming book.

Is Newman’s book transphobic? I don’t know. I haven’t read it. The majority of the detractors denouncing The Men have not read it either. Hough insists that she and Newman had discussed how trans people would factor into the premise of Newman’s book. But Twitter mobs have a track record of approaching literature as an exercise in rooting out sin rather than being open to complex questions.

Literature is not about being good. It is not about being right. Literature is about human things. It’s a space where writers grapple with the messiness, complexity, and nuance of being alive. It’s a rare opportunity to step inside the vantage point of someone else, to see the world through their eyes, and to think about things in ways you don’t usually. Literature is slow. It takes time and it requires an attention span. It can’t be consumed or understood in the space of a soundbite, or even the total time required for reading alone. Literature is debated and discussed at length, by eager minds who come to the same pages and leave with different conclusions. Literature is not religion and it is not law. It does not offer or follow a set of rules for how to avoid sin, how to seek absolution, or how to escape punishment. Literature, at its best, will empower the reader to ask hard questions rather than provide easy answers. It will challenge the reader to pause, be curious, and be humble.

Twitter is a storm of condemnation and offence. It is fast and it demands immediacy. It is the epitome of alienation, the human beings behind the screen reduced to the span of 280 characters. Empathy is scoffed at and discouraged. Calls for empathy are framed as fragility and even violence. Twitter has no time for or interest in messiness, complexity, or nuance. Twitter is too busy with the hunt for sin, crime, injustice. It seeks these out with ruthless fervour, attacking anyone who seems to step out of line. Twitter does all of this in the name of justice, or so it says. It claims that these attacks are rooted in love, in an attempt to restore humanity to those dehumanized. But it does this in the most dehumanizing way possible. It strips its targets of their human complexity, offering them no grace and no good faith. It does the same to the groups it claims to represent, by flattening the great diversity of thought and perspective that inevitably exists within any group of human beings.

As a result of the Twitter controversy, the Lambda Literary Prize withdrew Hough’s nomination, stating “we cannot knowingly reward individuals who exhibit disdain and disrespect for the autonomy of an entire segment of the community we have committed ourselves to supporting.” Hough’s anger at Twitter for its lack of serious engagement with the literature it attacks is now framed as Hough exhibiting disdain and disrespect for the autonomy of trans people – all trans people – despite the fact that Newman’s detractors do not speak on behalf of trans people generally.

Leaving Isn’t the Hardest Thing is tarnished with rumours that Hough is transphobic. Yet Hough has not backed down. She has instead taken to Substack to address the reality that writers, reviewers, and publishing houses are being held hostage by the wrath of Twitter.

Hough’s unusual path to the world of publishing perhaps positioned her well to be this kind of rebel. She didn’t learn the politicking of MFA programs and instead learned about the importance of having loyal friends. She didn’t come to literature as an exercise in reproducing social justice scripts, but as a queer person who has been silenced and wanted to speak her whole, human truth. The fact that this is not allowed anymore isn’t stopping her. The Twitter storm rages on.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.