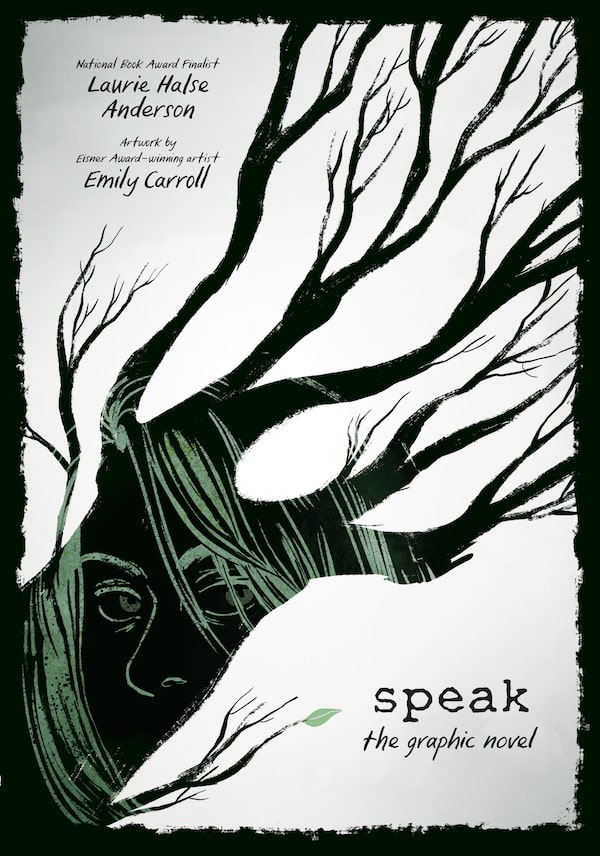

Speak: The Graphic Novel

By Laurie Halse Anderson, illustrated by Emily Carroll

FSG Books for Young Readers, 384 pages, $25.99

The graphic novel format seems tailor-made for Laurie Halse Anderson’s 1999 novel, Speak. In this much-lauded modern classic of YA literature, high-school freshman Melinda Sordino uses art to help her work through the trauma of sexual violence, providing her with an outlet for the turbulent thoughts she feels unable – and unwelcome – to say.

“Art and artistic expression play a significant part in Melinda Sordino’s transition from traumatized victim to empowered survivor,” Anderson writes in the foreword to her new, fully illustrated version of Speak. “The story and the form [of graphic novels] seemed to be a natural fit, but only in the hands of the right artist.”

Enter Vancouver artist Emily Carroll. After first coming to prominence in 2010, thanks to “His Face All Red,” a virally popular horror comic published online, she found mainstream success by collecting that and other frightful tales in her 2014 debut, the award-winning Through the Woods. A native of London, Ont., Carroll often explores subject matter akin to Southern Ontario Gothic—isolated characters in oblivious landscapes, quietly enduring grisly things. Her work is at once gorgeously stylized and wickedly gruesome, resembling a cross between the resplendent Disney artist Mary Blair and the macabre New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams.

It’s a style that Anderson must have figured would suit Speak perfectly. “Laurie often says she chose to work with me because I can depict ‘the light and the dark,’” Carroll says, “and I feel that I respond to her work for the same reason.” Their collaboration was similarly well balanced. “Laurie wrote the script, sent it to me, I did roughs of the pages and sent back notes (which were mostly: you’re going to want to remove a lot of the words – which she did), and so on back and forth.”

For one example of this kind of winnowing down and re-imagining, look at the scene in which Melinda’s rapist, Andy – whom she calls “IT” – insinuates himself behind her in the hallway at school. In Anderson’s novel, the author breaks from the staccato, fragmentary phrasing she uses throughout, and instead strings together clause after clause, breathlessly. She writes: “I can smell him over the noise of the metal shop and I drop my poster and the masking tape and I want to throw up and I can smell him and I run and he remembers and he knows. He whispers in my ear.”

The graphic novel jettisons this carefully constructed prose. Instead, Carroll torques what words are left into agitated lettering, and slashes the panicked experience across an entire two-page spread. She expands Melinda’s sense of horror so that it breaks free of panel borders entirely, splitting her world into distressing shards, haunted by ghostly limbs of trees that belong nowhere in that high-school hallway.

This kind of visual inventiveness recurs throughout the book’s scenes of triggering experiences and traumatic memories. “In terms of creative license,” Carroll says, “I think the places I pushed it (and re-drew) the most were probably the scenes with Andy: the party scene (and rape scene) required me pushing myself a lot to find the right imagery to convey the horror, as well as the confrontation with Andy towards the end of the book.”

The horror-movie symbolism that Carroll uses to give form to Melinda’s unspeakable truth is much like the art that Melinda herself creates to express herself. To convey the things she cannot say, she paints a cubist portrait of what high school looks like “beneath the surface,” or she collages together a statue out of Thanksgiving leftovers and a dismembered Barbie doll. As Melinda learns, and as Carroll shows, when words fail, art is articulate.