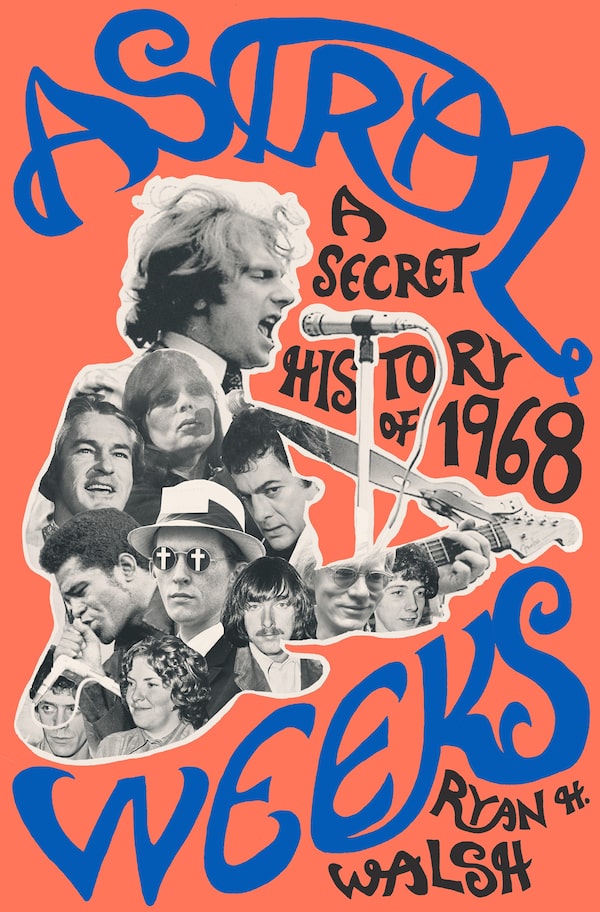

- Title: Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968

- Author: Ryan H. Walsh

- Genre: Biography/arts/history

- Publisher: Penguin

- Pages: 368

- Price: $36

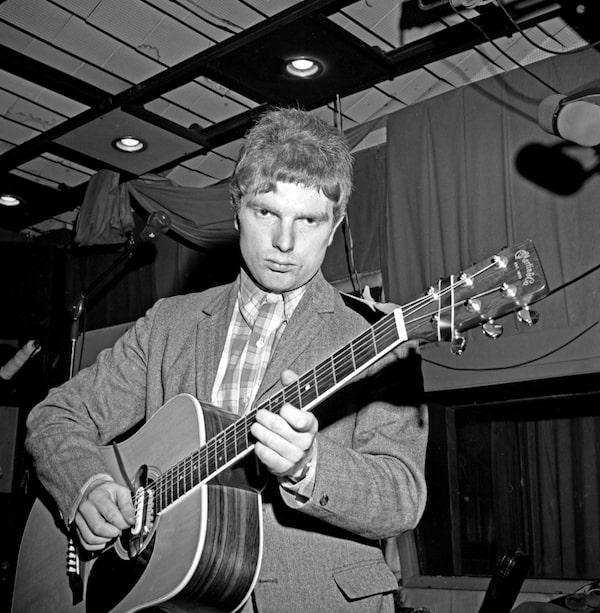

Musician Van Morrison plays a Martin acoustic guitar at a Bang Records recording session in the studio on March 28, 1967 in New York, New York. (Photo by PoPsie Randolph/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)Donaldson Collection/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

By 1968, the goings had gotten weird and the weird had turned pro. You knew that. What you didn’t know is that the weird had opened up a branch office in Boston.

And, in 1968, with the release of his mystic-fever mind-blower Astral Weeks, Van Morrison famously “ventured in the slipstream, between the viaducts of your dream.” Again, you knew that. But were you aware that the slipstream had come from Massachusetts’s capital city?

With his magnetic new book Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968, the author Ryan H. Walsh connects dots and leaves others untied, raising questions about the milieu of Morrison’s masterpiece while answering most of them, too. Walsh’s contextualization is excellent and unforeseen, with pages on the making of the 1968 album and Morrison’s short-lived Boston residency entertainingly outnumbered by stories on a psychedelic public television show, James Brown, a counterculture newspaper, a mob-controlled record contract, a botched bank robbery, Velvet Underground pop-ins and a peculiar hippie commune with a harmonica-playing messianic leader.

In his book, Walsh quotes Marilyn French, who wrote of 1968 in her bestselling novel The Women’s Room (which was inspired by her time at Harvard): “That year itself was an open door, but a magical one; once you went through it, you could never return.”

Handout

And, now, on the 50th anniversary of that year, Walsh with his own book takes a trip astral in its enlightenment. An album is applauded, with a sort of reverse demystification that explains the things you didn’t know you needed to know.

Speaking of context, Astral Weeks was the second solo album by Morrison, a now-legendary hot-tempered Belfast-born soulster with mercurial inspirations and a crabby disposition. In the mid-1960s, while with the Irish band Them, he had hits with Bert Berns’s Here Comes the Night, Big Joe Williams’s Baby Please Don’t Go and his own garage-rock classic, Gloria. In 1967, as a solo artist, he scored big with the single Brown Eyed Girl.

None of all that would have prepared anyone for Astral Weeks, a jazzy, free-flowing song cycle of cryptic lyrics, jasmine-scented notions and acoustic-orchestral situations. For Rolling Stone, Greil Marcus wrote that the music was not rock and roll in any ordinary or hyphenated sense: “What might seem arty at first proves to be a new place to go, a new kind of music to hear.”

Though the album was recorded in New York, its roots are in Boston, a city home to a flourishing folk-music scene in the early 1960s. By the time the 22-year-old Morrison arrived in nearby Cambridge with his wife, the folkies had ceded ground to the freaks. Record companies looking for the next Liverpool or San Francisco had found a new place — some called it the “Bosstown” sound.

Walsh starts his book where so many sixties stories begin: The 1965 Newport Folk Festival, where Bob Dylan plugged in and the folk purists tuned out. Walsh, who describes the summer evening as having taken on a funeral-like feeling after Dylan’s heavy-electric shenanigans, focuses on a skinny mouth-harp player named Mel Lyman. On an unlit stage, as confused, mournful people drifted from the event grounds, he closed out the proceedings with a solo version of Rock of Ages.

Lyman would become the leader of the Fort Hill Community, a Boston-based cult of acid evangelism and neo-transcendentalism in tight with the Timothy Leary crowd. The Community published the Avatar, an avant-garde newspaper to which Lyman contributed megalomaniac musings. His short, weird rise and fall threads Walsh’s book.

There’s rarely a dull moment to be had here. In a chapter entitled “The Silver Age of Television,” the astounded reader learns all about David Silver, a young British Shakespearean scholar who created wacky half-hour programs on Boston public television. One night, he orchestrated an arrangement on two channels, in which only viewers with two television sets could watch a Ping-Pong match.

Ryan H. Walsh. Credit: Marissa Nadler 2017

(Who had two televisions in 1968?)

Elsewhere, we get the news on Mark Frechette, a handsome non-actor plucked from the streets of Boston to co-star in Zabriskie Point, Michelangelo Antonioni’s unexplainable take on Death Valley nudity and the American counterculture. Frechette, a Mel Lyman devotee, would die in prison after attempting to rob a Boston bank.

“It was a good bank robbery,” Frechette would later protest to the press from jail. “Maybe it wasn’t a successful one, but it was real, ya know?”

Frechette’s explanation could probably also serve as a summation of Boston as a brief sub-hub of Sixties madness. As for the album Astral Weeks, most of the Boston band that helped Morrison develop the songs didn’t get to play on the actual recording.

The unpleasable Morrison himself didn’t care for the album, telling Toronto-based music writer Ritchie Yorke that the producers “ruined it” with strings overdubbed without his permission. And for all its critical acclaim, the record sold poorly.

From his cell, Frechette later despaired over the death of the sixties and the Boston scene. “We haven’t changed,” he said. “Everybody else is gone. Where did they go?”

Morrison, for one, moved on to Woodstock, N.Y., probably murmuring to himself as he left Boston:

In another time

In another place

In another face

Such is life in the slipstream, and such is Walsh’s book. Something is ventured, much is gained.

Brad Wheeler

Brad Wheeler