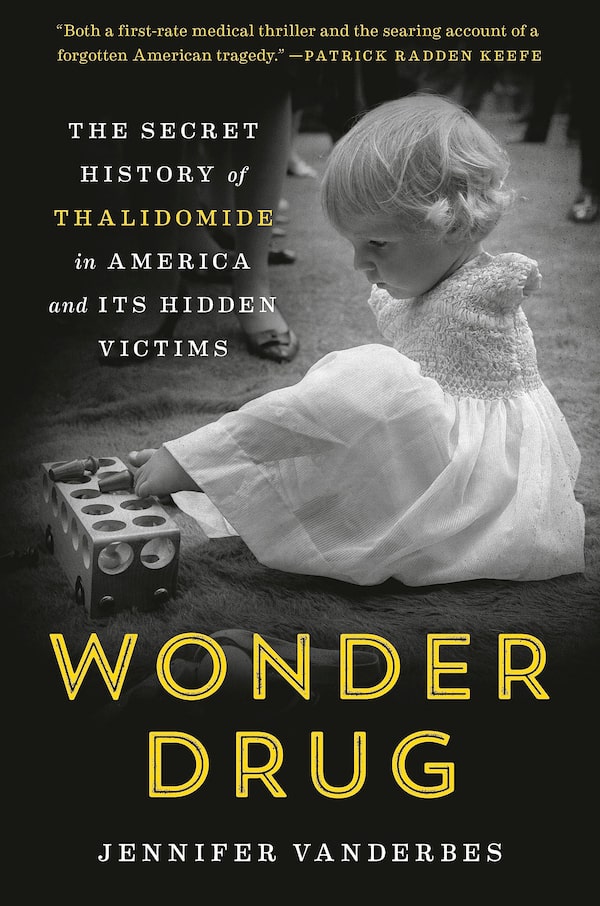

- Title: Wonder Drug: The Secret History of Thalidomide in America and Its Hidden Victims

Handout

- Author: Jennifer Vanderbes

- Genre: Non-fiction

- Publisher: Random House Publishing Group

- Pages: 432

There was an inevitable, sickening pattern to the distribution of the sedative and putative “wonder drug” thalidomide to an unsuspecting population. Thanks to Jennifer Vanderbes’s Wonder Drug, that inevitability has been deconstructed and explained.

With the meticulousness of a Maddow investigation, Vanderbes documents the complacency, the complicity, the collusion, the cover-ups and denials surrounding a drug that was supposed to be a safe sedative and was found to ease the nausea of pregnancy.

The pattern goes something like this: A drug is developed without rigorous testing (despite claims to the contrary) and sold or licensed to another country in the shortest possible time. Initial reports of adverse reactions are ignored. The pharmaceutical company’s sales representatives are told to push the drug hard, charm doctors, supply them with samples and encourage its use among unsuspecting patients, including pregnant women, without having to report on its efficacy or side effects. Babies are born with birth defects – typically phocomelia, or seal-like flippers, instead of fully formed arms and legs.

The company refuses to accept any link to its product and lobbies the government to allow distribution to continue. Then a medical professional discovers said link and tries to sound the alarm. By the time anyone pays attention, several dozen or even a hundred thalidomide babies have been born.

If the pattern ended there, it would be terrible but almost understandable. However, it continues with refutations by the drug companies, collusion from politicians, doctors and lawyers and the denial of justice to those damaged by the drug.

It happened in Canada. It happened on a larger scale in Germany. It happened to me in the U.K. – I have phocomelic arms, no right eye and severely impaired vision in the left. And it happened in the United States.

This runs counter to the prevailing narrative of thalidomide, which is that an intellectually rigorous, strong-willed scientist, the Canadian-born Frances Kelsey, who worked for the Food and Drug Administration in Washington, kept thalidomide out of the reach of U.S. consumers. This is a narrative I repeated when I made a BBC radio documentary to mark 40 years of thalidomide. I was privileged to interview Dr. Kelsey and was struck by her sharp mind and her insistence that the application submitted by Merrell, the U.S. company seeking to bring thalidomide to the United States, was not scientifically valid.

While it is undoubtedly true that Dr. Kelsey saved America from the mass distribution of thalidomide, Merrell appointed a number of “investigators” – doctors who would give samples of the drug to patients who were unaware that what they were consuming was experimental.

Upwards of 1,200 physicians were supplied with thalidomide. An estimated five million tablets were consumed – with inevitable results. Dr. Kelsey herself worried about how much thalidomide had seeped into the population. The FDA’s inquiries were thwarted by doctors who refused to divulge patients’ names or whether they were pregnant. The official FDA account said fewer than a dozen thalidomide babies had been born in America.

The reality was somewhat different. Having failed with its first licensee, Smith, Kline & French, the drug’s German manufacturer, Chemie Grünenthal, found a more willing host in Cincinnati-based Merrell. Babies were born with limb damage and other abnormalities. Only recently, though, did they start to recognize each other, organize themselves and start campaigning for justice – 50 years after they were harmed in the womb.

Because that prevailing narrative had taken root so effectively, the U.S. – unlike other countries where thalidomide wrought havoc – has no process for diagnosing thalidomide damage and no form of compensation beyond individual lawsuits, some of which continue to be contested.

In 1964, the U.S. Department of Justice decided not to prosecute Merrell because it had incorrectly assumed that only one child had been born with limb damage in the U.S. In Germany, with thousands of damaged children, the prosecutor abandoned the criminal trial against Grünenthal “in the public interest.”

Vanderbes’ book follows the chronology from Grünenthal’s Nazi links through to the early meetings in the past decade of the US Thalidomide Survivors group. The chronology is necessary to understand how the tragedy unfolds, but Vanderbes never loses sight of the fact that she is telling the story of a different group of people, beginning many chapters with a brutal thumbnail of the life of a survivor:

“I was born in Oklahoma City … both arms were missing at the shoulders, and I had two short leg stumps above the knee … soon after I was born, the doctor put my mom in a hospital room with another woman, whose baby was still born … They wanted my mom to get used to the idea I was going to be gone, in an institution. They told my mom that I would be significantly ‘retarded.’ I am now a lawyer.” – Jan Taylor Garrett

Vanderbes has a deft pen and a thoroughness worthy of Dr. Kelsey herself. The action shifts from one country to the next in the manner of a John le Carré thriller. Coming hot on the heels of a documentary, it is hoped the U.S. government will own up to its errors and ensure recognition and adequate support for the survivors – the group estimate they number around 100 – whose bodies were literally test beds for modern drug safety.

Geoff Spink is a British thalidomide survivor, campaigner and journalist.