THE BASICS

What was #AfterMeToo about?

So far, #MeToo has been a moment of reckoning for individuals: Powerful men held accountable for sexual assault, and survivors sharing personal stories. But what about institutions? How can industries, workplaces and cultures prevent future Harvey Weinsteins from flourishing?

That's where #AfterMeToo comes in. It was a two-day symposium being held Dec. 5-6 at The Globe and Mail's Toronto headquarters. On Tuesday, it brought together Canadian film and TV professionals with trauma experts, lawyers and activists to come up with practical solutions for sexual harassment in the film industry. On Wednesday, at a town hall, members of the public had a chance to question the experts on what they've learned.

For more context on the issues, The Globe has collected some recommended reading from its archives about the latest efforts to reform laws, law enforcement and political institutions. Read more below.

THE EVENT

The roundtables

Tuesday's discussions brought together experts from all parts of the film industry, from actors and directors to lawyers and writers, as well as trauma experts and legislators. Globe writers moderated the discussions.

#AfterMeToo roundtable discussions in progress. It’s happening! https://t.co/KtVAOIp3T4 pic.twitter.com/qnqBdWyjkz

— Hannah Sung (@HannahSung) December 5, 2017

The town hall

On Dec. 6, 1989, a gunman entered École Polytechnique in Montreal and killed 14 women claiming, "I am fighting feminism." This day is now known as the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women. The Globe's town hall was held on the 28th anniversary of the Montreal massacre.

On Wednesday, the #AfterMeToo organizers shared their recommendations and promised a detailed report of all its recommendations in the winter of 2018, including a timeline for action. The recommendations include:

- Creating an independent national body to oversee formal complaints in the industry, with the power to “resolve claims by compensatory, systemic and punitive measures.”

- A “unified industry-wide response” to sexual violence, harmonizing policies among unions and possibly pressing for amendments to Canadian labour laws.

- Widening the definition of “workplace” to include events like wrap parties or networking functions.

- Creating online systems for survivors to report their complaints.

- Mandatory yearly education for film-industry workers.

- Creating an industry fund for services like mental health care and legal advice.

- Pressing governments to do more to provide mental health and trauma support for survivors.

At The Globe's town hall, members of the public had the opportunity to listen, learn and ask questions of the experts regarding the panellists' recommendations. Get caught up on what the speakers said via The Globe's and #AfterMeToo's Facebook pages, or on Twitter through the hashtag #AfterMeToo or the @aftermetoo account.

Watch Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould’s full speech at the #AfterMeToo symposium

Robyn Doolittle describes how the Unfounded investigation into police handling of sex assault cases came to be

Mia Kirshner says now is the moment to push for change around sexual misconduct in the workplace

About our keynote speaker

Jody Wilson-Raybould is the federal Justice Minister, Attorney-General and MP for Vancouver Granville. She entered the legal profession in the 2000s as a B.C. Crown prosecutor and advisor to the B.C. Treaty Commission before being elected twice as Regional Chief of the B.C. Assembly of First Nations. Ms. Wilson-Raybould is a member of the We Wai Kai Nation, and is descended from the Musgamagw Tsawataineuk and Laich-Kwil-Tach peoples, part of the Kwakwaka'wakw people.

About Robyn Doolittle

Journalist Robyn Doolittle will be speaking at Wednesday's event too. Ms. Doolittle joined The Globe's investigative team in 2014 after nearly a decade reporting for the Toronto Star, where her reporting on mayor Rob Ford's personal life ultimately won her the 2014 Michener Award for public service journalism and became the basis for a national bestselling book, Crazytown. Earlier this year, her 20-month-long Unfounded investigation – which revealed that police forces in Canada dismiss one in five sexual-assault cases as baseless – prompted dozens of law-enforcement agencies to act by reviewing their policies and reopening old cases. The Unfounded project has since won four Online Journalism Awards, a North American Digital Media Award and a Data Journalism Award.

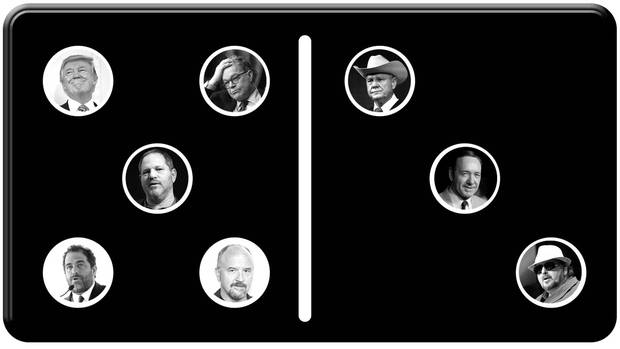

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION/THE GLOBE AND MAIL (IMAGES: AP, REUTERS, AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

RECOMMENDED READING

How we got here

Harvey Weinstein: In October, a New York Times investigation revealed that, for decades, one of Hollywood's most powerful producers had allegedly raped and harassed scores of women in the film industry. Within days, he was fired from his company, and film industry groups severed ties with him. More and more accusers came forward – as many as 93 so far – and police in Los Angeles, New York and Britain have opened investigations.

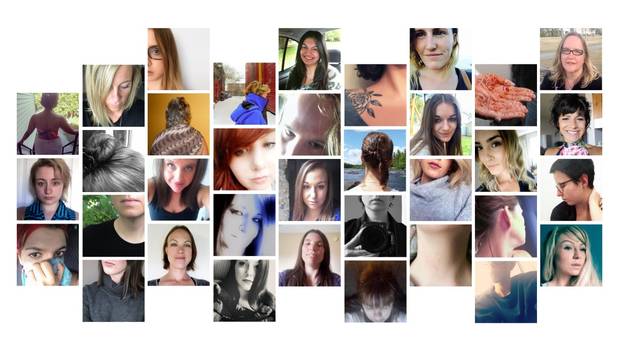

#MeToo: Seeing Mr. Weinstein face such swift, severe and public consequences led more survivors to come forward about harassment in film and TV, the news media, politics and business. Alleged abusers include actor Kevin Spacey, comedian Louis CK, TV news host Charlie Rose and Alabama Republican Senate candidate Roy Moore. (The day of the #AfterMeToo town hall, Time magazine named the #MeToo hashtag and the woman who came forward as "person of the year.") Since October, The Globe and Mail has been compiling a list of high-profile cases. There are nearly 70 names on it.

#AfterMeToo: The week after the initial Weinstein story broke, Canadian actress Mia Kirshner spoke out about her "ordeal" with the Hollywood mogul, writing for The Globe and Mail that "he attempted to treat me like chattel." But she said she didn't want to give Mr. Weinstein more attention when the broader issues of sexual harassment needed to be addressed. Hence #AfterMeToo, which Ms. Kirshner organized with filmmakers Aisling Chin-Yee, Allia McLeod and Freya Ravensbergen, in partnership with Fluent Films and The Globe and Mail.

More reading:

Institutional change: A rape-culture reading list

Laws and law enforcement

The Weinstein effect may have emboldened people to speak out against their abusers in the press, but survivors still face many barriers in getting justice through the police and court system.

One such barrier – Canadian police forces who declare sex-assault cases "unfounded," or lacking enough evidence to pursue an investigation – has been the subject of a years-long investigation by The Globe and Mail's Robyn Doolittle. Data gathered from more than 870 police forces revealed that one in five claims were dismissed as baseless, and that there are flaws and inconsistencies across the country in how police investigate complaints.

The Unfounded investigation spurred dozens of police forces to reopen old cases and review their policies; the federal government drafted a five-year plan to prevent gender-based violence; and Statistics Canada decided to resume counting unfounded cases, which they had previously stopped doing.

More reading:

Lawmakers

The lawmakers who decide how sexual assault is prosecuted are liable to experience harassment themselves. In the past few years, Parliament Hill has seen a Conservative senator suspended as police investigated him for sexual assault, a charge of which he was ultimately acquitted; a Liberal minister who left cabinet over a relationship with a female staffer and her mother; and a Liberal MP who quit caucus after facing harassment allegations. "Harassment is a problem all over the place – Parliament Hill, but also workplaces across the country," Environment Minister Catherine McKenna told The Globe. "We know we need to be doing more, we need to counter harassment, sexism of all sorts."

Federal employees have to rely on a patchwork of policies to have their complaints heard, but the Liberal government is introducing a new law, Bill C-65, to address that. It would put the onus on employers to protect their employees and handle harassment complaints on the Hill the same way as all other federal workers.

Canada's isn't the only national government under pressure to do better. In Britain, Prime Minister Theresa May has promised to do more to protect staff in the legislature after a string of accusations against senior politicians in her Conservative government. In the U.S. Senate, Democratic lawmakers recently introduced the ME TOO Congress Act to overhaul the complaint policies on Capitol Hill and require training on sexual harassment.

More reading: