A line wraps around the corner to see Alan Ladd starring in Paratrooper at the Criterion in Times Square in 1953.Courtesy of Bow Tie Cinemas

Given that movie theatres are in the business of big, splashy, loud Hollywood mega-entertainment, it is quietly funny that theatre-owners tend to have the absolute lowest profiles of anyone in showbiz. With the exceptions of AMC Entertainment’s social-media-savvy chief executive Adam Aron – who leveraged the meme-stock craze of 2021 to become the head of a suddenly red-hot company – and Quebec’s Vincenzo “Mr. Sunshine” Guzzo, the Dragons’ Den fire-breather who heads Cinémas Guzzo, exhibitors let the movies do the talking.

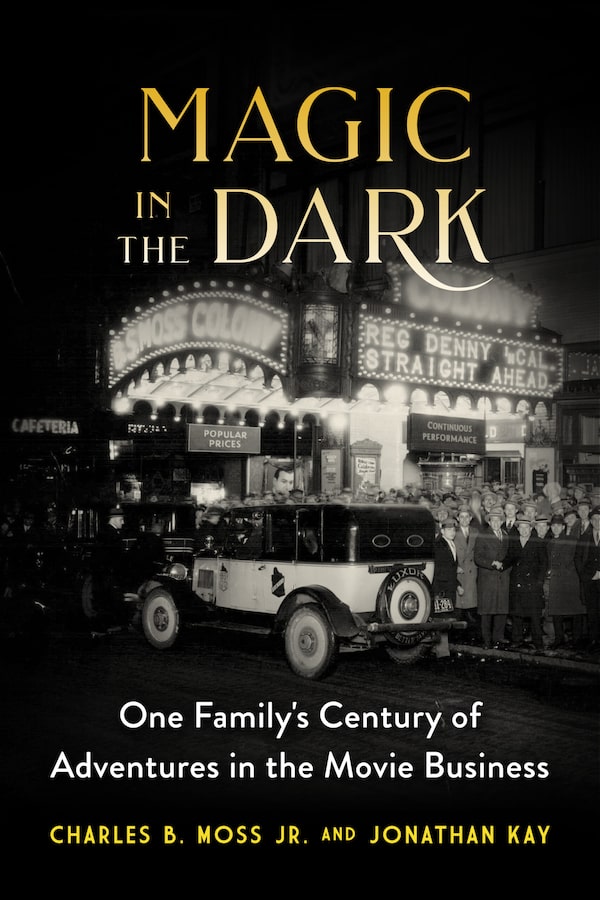

Which is why the new book Magic in the Dark: One Family’s Century of Adventures in the Movie Business is such a fascinating read. Written by Bow Tie Cinemas chief Charles B. Moss Jr. (in collaboration with Toronto-based journalist Jonathan Kay), the book offers not only a compact 100-year history of moviegoing, but a rare and candid peek into the sometimes hilarious, sometimes scandalous, always head-spinning inner workings of that crucial, overlooked stage of filmmaking: the actual act of showing movies to audiences.

With Magic in the Dark now available through Canada’s Sutherland House Publishing, Moss – whose company is the eighth-largest theatre chain in the United States – spoke with The Globe and Mail about the past, present and perilous future of moviegoing.

Magic in the Dark: One Family’s Century of Adventures in the Movie Business was written by Charles B. Moss and Jonathan Kay.Courtesy of Sutherland House Books

Your new book chronicles the history of Bow Tie, which has been family-owned and operated for four generations. But only the last chapter takes on the pandemic. What has the situation been since March, 2020?

Bow Tie’s issues are the industry’s issues, and we are facing a very difficult time. If you look at the health of the film industry, taking into account every type of delivery system, the future is bright. But from a theatre standpoint, it’s very challenging. Exhibition has weathered a lot of storms: radio, television, VHS, cable, DVD. But now our suppliers, the studios and distributors, are our competitors, too, with streaming. I don’t think there’s another industry where that’s the case. The industry has to restructure itself financially and repurpose its real estate to other uses.

You mean theatre-owners need to get out of the theatre business?

Well, you have to reconstruct your budget to reflect lower income. To do that you need to cut payroll, other operating expenses, then you either restructure your economics or, if you have a well-located property, convert it to another use. We have a location that used to be quite good, but it’s fallen on hard times. And we’re seriously looking at converting it into one-bedroom apartments.

One of the complaints moviegoers have coming out of lockdown is that theatres didn’t use the shutdown time to make improvements in the experience once doors reopened. The situation can be dire outside major cities.

Most people in exhibition understand that if you want to keep people coming, you have to give them a great experience that starts when you open the front door. I’m not sure that every exhibitor in the industry wants to make the investments to accomplish that, which is so short-sighted because it’s more costly not to do it. Your guests needs to be treated with respect and dignity.

Streaming is an existential threat. But Bow Tie manages the Paris Theatre in New York – the last single-screen movie house in Manhattan – which is currently leased by Netflix.

I can’t speak to the economics of that because it’s confidential information, but this is a one-off situation. It’s the premiere art-house in New York, and in today’s environment operates in a world unto itself. It’s a small win-win situation with no adverse consequences on the overall picture for us. We don’t manage other people’s properties, but we did it here. The issue here is not that the producer or distributor can or cannot own their own theatres, but it’s how they make their product available. A distributor can own a theatre and as long as they give you the same opportunity to play their movie, there’s no monopoly situation.

The B.S. Moss Flatbush Theatre, located on Church St. just off Flatbush Ave. in Brooklyn.Courtesy of Bow Tie Cinemas

Can theatres survive playing only large-scale, franchise-heavy movies like the new Spider-Man, which seem to be the only movies drawing large-scale audiences?

That’s a hard question, but not knowing the answer has never stopped me from giving an opinion. So: I think it’s a real threat. Tent poles are becoming more and more important. But, COVID aside, if you can restructure your economics as a theatre-owner so you can afford to gross less money and still be profitable, you become a viable venue for smaller films. I think there’s a good shot for that type of product, your Fox Searchlight type of movies, to come back stronger in the theatrical marketplace than today. But it’s a total guess.

Where do you see Bow Tie in the next five years?

Like everyone else, we’ve done belt-tightening. In the past two years, we’ve shed marginal theatres. This is an era of battening down your hatches. My grandfather did that after he built up the vaudeville circuit and saw movies coming. The only wild card is this virus. If we had this conversation a year ago, I would say the next year, it’d all be over. But it’s all a wild card now.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Plan your screen time with the weekly What to Watch newsletter. Sign up today.

Barry Hertz

Barry Hertz