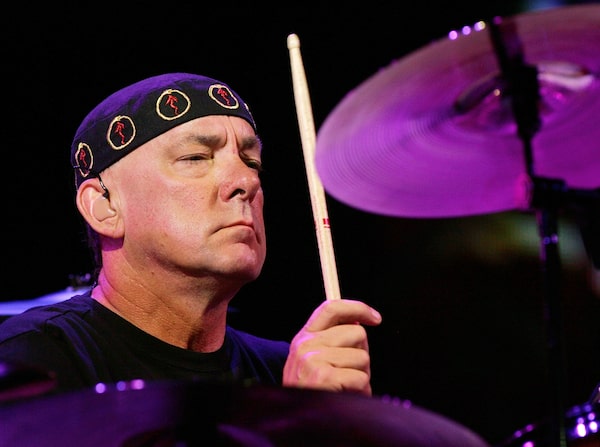

Neil Peart, seen here on May 6, 2008, wrote more than lyrics. He penned articles for Modern Drummer magazine, authored multiple memoirs and filed lengthy blog entries.Jesse Grant/Getty Images

On Jan. 7, Neil Peart, the virtuoso percussionist and philosophic lyricist for Rush, succumbed to glioblastoma. The Tragically Hip’s iconic front man Gord Downie died from the same ruthless brain cancer in 2017. Two of Canadian rock’s most peculiarly gifted and deeply literate thinkers are now gone.

Mr. Peart, retired and 67 years old at the time of his death, will be remembered for an active style of drumming that was ambitious and flamboyant yet exact – his jazzy improvisation meticulously planned. He was a cymbal-smashing sticksman who felt comfortable in difficult time signatures – like a circus daredevil on the highest of wires. Mr. Peart dared the air-drummers into their highest achievements, and he believed both in classical tools, such as the timpani, and modern electronic implements, too. As an insistent free spirit, he filled his life with adventure; in the studio and onstage, he stuffed songs with drum fills that tumbled like artful dominoes and impressionistic solos that were near operatic.

Aside from regretful 1980s fashion choices and an unpopular one-time enthusiasm for right-wing writer Ayn Rand, Mr. Peart hit all the right notes.

Despite the razzle-dazzle, the native of Port Dalhousie, Ont., kept Rush’s high-prog chugging along. “Neil pushes that band, which has a lot of musicality, a lot of ideas crammed into every eight bars,” former Police drummer Stewart Copeland told Rolling Stone magazine in 2015, "but he keeps the throb, which is the important thing.”

Lesser known was Mr. Peart’s love of literature and language. He had a poet’s ear and reading lists as long as one of his drum solos. His older lyrics, inspired by Ms. Rand and J.R.R. Tolkien were dismissed by critics as being inane. “A lot of the early fantasy stuff was for fun,” Mr. Peart once admitted, “because I didn’t believe I could put something real into a song.” With time, Mr. Peart’s lyrics became more thoughtful and relevant. The 1980 single The Spirit of Radio, for example, concerned that media’s corporatization and the harsh realities of the music industry: “Glittering prizes and endless compromises shatter the illusions of integrity.”

I interviewed Mr. Peart just once, in 2007, upon the release of Rush’s Snakes and Arrows. The chat took place in the band’s Toronto rehearsal space, where Mr. Peart led me past his spaceship/time machine of a drum kit. What struck me was his profound respect for people who make their living by writing – novelists, mostly, but even an ink-stained rock critic. “I thought we could sit over there," he said, his tone deferential and excited as he motioned to a pair of folding chairs next to a roadie case. “You can put your tape recorder right here."

The Rush rhythmatist wrote more than lyrics. He penned articles for Modern Drummer magazine, authored multiple memoirs and filed lengthy blog entries. “I wrote that for people like you," he told me, referring to a lengthy essay on the making of the Snakes and Arrows album. (He not only wrote the essay, but an additional 2,893-word online opus on the writing of the essay.)

His passion for novels and novelists is on full display on his website, Bubba’s Book Club. In his last post, apparently written around 2014 (before his three-year battle with cancer), Mr. Peart explained why he wrote about books, saying his simple motive was to “share the love.” Unlike rock critics who blew raspberries at Rush early in its career, Mr. Peart focused only on works he adored. In his final Bubba’s Book Club issue he charismatically praised Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue, Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, Douglas Coupland’s Eleanor Rigby and Lynn Coady’s The Antagonist.

For his intellectualism, Mr. Peart earned the nickname The Professor. He was known to be precise, as former Universal Music Canada publicist Marcus Tamm found out when he dashed off a blurb on a Rush event a decade or so ago. He had no idea that the 200-word press release would be sent for final approval to Mr. Peart, who noted a trite superlative and Mr. Tamm’s double use of an adjective. “Neil Peart himself had caught my errors, and ever since it’s made my own editing process more diligent," Mr. Tamm told The Globe and Mail. "I think of him specifically almost every time I write anything.”

Mr. Peart, seen here on July 28, 2007, saw the ephemerality of life and rock.Ethan Miller/Getty Images

It’s a wonder why more drummers aren’t wordsmiths. There is, after all, a shared mathematical capacity and mental method to rhythmically set words together and organize beats. What would be rare is doing both so ambitiously as Mr. Peart.

My favourite Peart anecdote to surface after the musician’s death came from Canadian filmmaker-journalist Andrew Gregg. In high school during the late 1970s in Acton, Ont., Mr. Gregg and a friend wore uniform numbers 21 and 12 in tribute to Rush’s 1976 masterpiece 2112. “For us, being 15 years old, having Toronto bands like Goddo, Max Webster and Rush making it big was amazing,” Mr. Gregg told The Globe. “You’re in this little tannery town an hour west of Toronto. These bands were from the big city on the horizon, and we were in awe of them.”

The first side of 2112 is filled with a titular suite about a dystopian world in which rock music is forbidden. It’s a theme also found in Ben Elton’s jukebox musical We Will Rock You (based on the songs of Queen) and some of The Who’s 1972 album Who’s Next, which uses material from the band’s abandoned sci-fi rock-opera project Lifehouse.

Although Rush and The Who were loud overlords of 70s classic rock, chief songwriters Mr. Peart and Pete Townshend were never so caught up in the genre to believe its high standing would endure. Rock albums of the past were the novels of the music world, with concerts filling the secular role of church-tent revivals. Being a Rush fan in particular could practically be one’s whole personality.

It’s no longer that way. Although rock isn’t dead, as often suggested, its stature as a subculture (or even the dominant popular music style) is. Mr. Downie is gone, Mr. Peart is gone. The year 2112 is a long way away, but Mr. Peart saw the ephemerality of life and rock. His message? Believe in ancient miracles, share the love and enjoy things while they last.

Live your best. We have a daily Life & Arts newsletter, providing you with our latest stories on health, travel, food and culture. Sign up today.

Brad Wheeler

Brad Wheeler