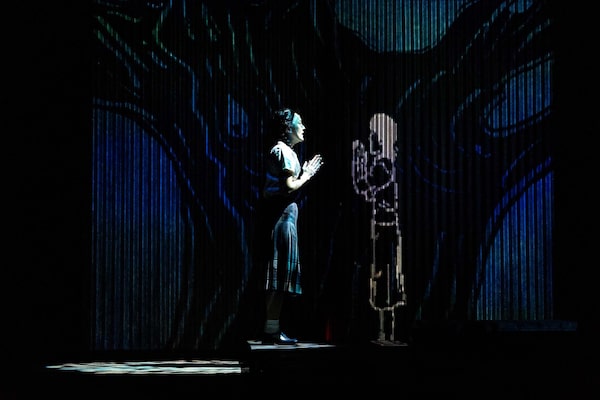

Yoshie Bancroft and Kevin Takahide Lee in Forgiveness.David Cooper/Handout

- Title: Forgiveness

- Written by: Hiro Kanagawa

- Director: Stafford Arima

- Actors: Yoshie Bancroft, Griffin Cork

- Company: The Arts Club and Theatre Calgary

- Venue: Stanley Industrial Alliance Stage; then Max Bell Theatre

- City: To Feb. 12 in Vancouver; then March 7 to April 1 in Calgary

What is a memoir minus a memoirist?

In his 2014 Canada Reads-winning book, Forgiveness, Mark Sakamoto wrote about two of his grandparents – and what he learned from their resilience during the Second World War.

What connected their experiences – one a white Canadian captured by the enemy abroad, the other a Japanese-Canadian treated as an enemy back home – and brought them to a kind of emotional closure on the page was the author himself, his very existence as their shared grandson.

In a new large-scale stage adaptation of this book, however, Mitsue Sakamoto, Sakamoto’s paternal grandmother, and Ralph Maclean, his maternal grandfather, take control of their narratives – with Mark Sakamoto nowhere to be found.

Forgiveness, written by playwright Hiro Kanagawa and currently on stage at the Arts Club in Vancouver ahead of a run at Theatre Calgary, sees Mitsue and Ralph team up to tell their stories, occasionally together, but mostly side by side.

The staging by director Stafford Arima slips back and forth between their worlds and perspectives with the help of giant shoji – Japanese sliding doors – designed by Pam Johnson and frequently covered with contextualizing projections of historical pictures and animations.

The first act of Forgiveness flashes forward to the days leading up to a dinner party in Medicine Hat in 1968, where the two narrators meet for the first time.David Cooper/Handout

Mitsue (Yoshie Bancroft) is raised in Vancouver, in a seemingly upwardly mobile Japanese-Canadian family amid a larger community coming under attack from increasingly organized anti-Asian racism in the lead-up to the war.

Ralph Maclean (Griffin Cork), meanwhile, grows up on the other side of the country with an abusive father in the Magdalen Islands – a remote, impoverished milieu where we see the racism of his white contemporaries as a response to their own frustrations with the world and their place in it.

As war breaks out again in Europe in 1939, Mitsue is considering marriage proposals and facing career options limited by a combination of gender and race discrimination; Ralph, on the other hand, fudges his birthday and enlists as soon as possible, eager to escape his circumstances by fighting Germans – he expects – with the Royal Rifles of Canada.

The first act of Forgiveness also flashes forward to the days leading up to a dinner party in Medicine Hat in 1968, where the two narrators will meet for the first time owing to Mitsue’s son Stan (Daniel Fong) and Ralph’s daughter Diane (Allison Lynch) having become romantically involved in a changing Canada.

Griffin Cork, Fionn Laird, and Jacob Leonard in Forgiveness.David Cooper/Handout

Kanagawa’s play initially teeters as if from one coast to the other, one time period to another. But it stabilizes as Ralph and Mitsue’s stories turn into contrasting tales of survival following Japan’s launch of its December, 1941, surprise offensive.

Ralph, who has been stationed in Hong Kong, is quickly captured by the Japanese. Mitsue’s family, meanwhile, has their property confiscated and rights taken away one after another.

As other Japanese-Canadians are sent to camps, Mitsue and Hideo (Kevin Takahide Lee), the boyfriend she hastily married to not be separated from, are forced to relocate to an Alberta sugar-beet farm where they are barely housed in a chicken coop and their work is exploited from dawn to dusk.

On the other side of the world, Ralph experiences a cavalcade of horrors as a prisoner of war – witnessing the deaths of friends from torture, disease, accidents and the whims of his captors.

Without the grandson thinking about his family history to bridge these stories, this adaptation might be criticized of equivalence. But I found the two plot lines compellingly complementary and that they both filled in gaps left by our cultural oversaturation of Western Front-focused depictions of the Second World War.

Still, dramatically, it feels like something is missing. Kanagawa’s play is told in short, clear scenes that Arima and a strong cast keep moving forward at a cinematic clip – but the promised psychological process of the title is rushed in Ralph’s case and unclear in Mitsue’s.

Yoshie Bancroft as Mitsue in Forgiveness.David Cooper/Handout

Sakamoto’s book has its gaps, too – but by swerving into his own story and that of his parents and exploring intergenerational trauma and resilience, it found a kind of conclusion.

That memoir now feels very much like a product of the Obama era in which it was written, with its climactic moment where the writer finds himself working in Ottawa and in the very room where prime minister Mackenzie King had made decisions that so deeply affected the lives of his grandparents, his parents and, indeed, his own.

The play, on the other hand, built up to a Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner-lite meal in the 1960s – capped with the Guess Who’s These Eyes playing in the background – comes to what feels like an older and overly triumphant Trudeaupian ending. We sadly are regularly reminded of late how anti-Asian hate in North America did not evaporate with the advent of multiculturalism (a word anachronistically dropped in the pre-war portion of the play).

In terms of what is gained by putting Forgiveness on a stage, it allows for a supporting cast of white and Asian actors to alternate between playing oppressors and the oppressed in a theatrically interesting way.

The most riveting acting in this regard comes from Jovanni Sy who plays both Mitsue’s lovable father and Camp Commandant Tetsutaro Kato, a real historical figure whom Ralph ended up serving for years at a PoW camp. The echo of the earlier character that remains in this monstrous one makes for a rich performance. Arima’s production could have leaned into this more; a succession of costumes and wigs can make it feel like a musical without music as well as a memoir without a memoirist.

J. Kelly Nestruck

J. Kelly Nestruck