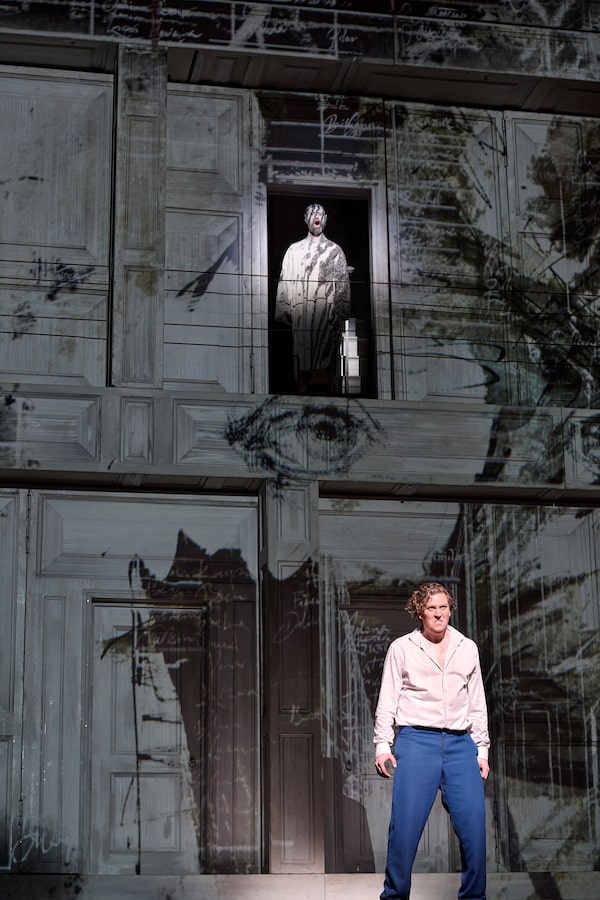

Gordon Bintner as Don Giovanni and Mané Galoyan as Donna Anna in the Canadian Opera Company’s production of Don Giovanni.Michael Cooper 2024/COC

Keep up to date with the weekly Nestruck on Theatre newsletter. Sign up today.

- Title: Don Giovanni

- Written by: Mozart

- Director: Kasper Holten

- Conductor: Johannes Debus

- Company: Canadian Opera Company

- Venue: Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts

- City: Toronto

- Year: To Feb. 24, 2024

Should we feel sorry for Don Giovanni? In an age when privilege is being questioned more than ever, affording pity to the powerful is a prickly issue. The Canadian Opera Company’s current presentation of Don Giovanni asks us to consider the role of pity, and its twin, grace, in a presentation that integrates arresting visuals and sensitive musicality.

Based on a play by 17th-century Spanish dramatist Tirso de Molina, Mozart’s opera is one of the most popular works within the classical canon. The beautifully poetic score and librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte’s mix of comedy, drama and the supernatural has been an audience favourite since its premiere in Prague in 1787. The nobleman Giovanni (Gordon Bintner) and servant Leporello (Paolo Bordogna) roam through Europe, the latter keeping a running tab of the former’s sexual conquests.

David Leigh as the Commendatore, above, and Gordon Bintner as Don Giovanni.Michael Cooper 2024/COC

After killing the Commendatore (David Leigh), Giovanni must deal with the fallout from the dead man’s daughter, Donna Anna (Mane Goloyan); her intended, Don Ottavio (Ben Bliss); ex-flame Donna Elvira (Anita Hartig); new flame Zerlina (Simone McIntosh) and her almost-husband Masetto (Joel Allison). Eventually the nobleman meets his comeuppance in a fiery finale of voices.

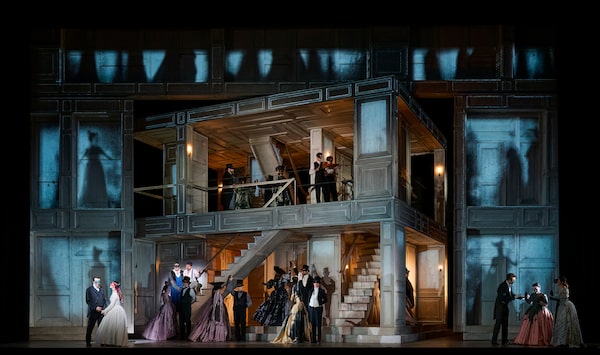

The Kasper Holten presentation at the Four Seasons Centre (under associate director Amy Lane and assistant director Marilyn Gronsdal) is a co-production with Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Gran Teatre del Liceu, the Israeli Opera and Houston Grand Opera, and was first presented in London in 2014. Its movable two-tier boxy set (by set designer Es Devlin) is comprised of a line of doors onto which are projected a successive series of visual motifs: spiralling landscapes, ghostly silhouettes, messy columns of written names – the famous “catalogue aria” of Giovanni’s conquests writ (literally) large. The visuals, by projections designer Luke Halls and projection associate Gareth Shelton, offer a good reminder that Giovanni’s world is, in fact, far less colourfully sensuous than chokingly monochrome.

That claustrophobia is something the production shares with the COC’s previous (and far more daring) staging of Don Giovanni in its 2014-2015 season, when Russian director Dmitri Tcherniakov presented a contemporary vision of a titular anti-hero whose pathological deception stemmed from a deep-seated sense of despair. Holten’s vision is decidedly less grim if no less pointed. Giovanni is presented as a dashing late 19th-century aristocrat who is haunted – quite literally at points – by his past choices and the isolation they have wrought.

Alongside the Edwardian-style waistcoats and voluminous dresses (by costume designer Anja Vang Kragh) the stage is filled at points by sylph-like figures clothed entirely in white, some with their faces obscured. They match the ghostly figure of the murdered Commendatore, who stalks both levels of the set and provides an ominous counterpoint to Giovanni’s manic joy. Servant Leporello and ex-lover Donna Elvira join their ranks at the final act, their dealings with the Don leaving them vampirized, empty, shells of their former selves.

So the question remains: Is it right to feel pity for a figure so adept at using people thusly? Holten stages Giovanni to walk into various scenes in which he plays no part, sometimes silently observing, sometimes haltingly trying to connect – but always he remains alone. Despite – or perhaps because of – the technological wizardry, the production’s focus on humanism is made explicit, especially during the delivery of Fin ch’han dal vino (the Champagne aria), when Giovanni is in the middle of a series of spiralling geometric projections. This is no winking seducer, grandiose criminal or moustache-twizzling bon vivant; this Giovanni is lonely.

Bintner is eminently watchable in the lead, using both flexible vocality and immense physicality to convey a sadness clothed in machismo. His delivery of the famous Deh, vieni alla finestra (Oh, Come to the Window) is richly nuanced and thoughtfully coloured, revealing a tiny if fascinating glimpse into the psyche of a man who is in constant need of validation. He is complemented by a strong cast, particularly soprano Anita Hartig as Donna Elvira. Her Mi tradi quell’alma ingrata (That ungrateful wretch betrayed me) offers a clarion tone and vocal flexibility in wrestling with anguished feelings that swing between vengeance and pity for the man who deceived her.

A scene from Don Giovanni. The production's moveable two-tier boxy set is comprised of a line of doors onto which are projected a successive series of visual motifs.Michael Cooper 2024/COC

This pity, which Elvira berates herself for, is one the audience is forced to confront for themselves. Holten dispenses with the traditional ensemble scene, preferring the dramatic conclusion of the Vienna 1788 presentation, in which the titular Don is dragged to hell. (Director Milos Forman also used it in the 1984 film Amadeus.) Though uncommon within many contemporary presentations, the drama cements the production’s wider theme.

Conductor and COC music director Johannes Debus leads the orchestra through a careful and dramatic reading, offering a clipped tempo in the overture and more languorous timing throughout. The pacing of the recitatives – spoken portions, played on a piano by Simone Luti – occasionally work against needed dramatic momentum, but underline the consideration given to character development. As the projections go dim and he is left alone onstage, Don Giovanni, it would seem, actually has a heart.

In the interest of consistency across all critics’ reviews, The Globe has eliminated its star-rating system in film and theatre to align with coverage of music, books, visual arts and dance. Instead, works of excellence will be noted with a critic’s pick designation across all coverage. (Television reviews, typically based on an incomplete season, are exempt.)