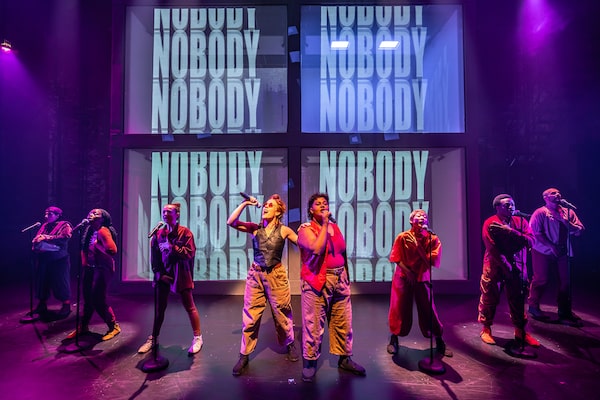

The cast of Universal Child Care sing in a scene from the new production by Quote Unquote Collective and Canadian Stage. From the left: Mónica Garrido Huerta, Germaine Konji, Norah Sadava, Fiona Sauder, Anika Venkatesh, Takako Segawa, Joema Frith, and Alex Samaras.Dahlia Katz/Handout

Keep up to date with the weekly Nestruck on Theatre newsletter. Sign up today.

Title: Universal Child Care

Book by: Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava

Music and Lyrics by: Amy Nostbakken

Director: Amy Nostbakken

Actors: Joema Frith, Mónica Garrido Huerta, Germaine Konji, Norah Sadava, Alex Samaras, Fiona Sauder, Takako Segawa, Anika Venkatesh

Companies: Quote Unquote Collective and Canadian Stage

Venue: Berkeley Street Theatre

City: Toronto

Year: To Feb. 25, 2024

Critic’s Pick

Quote Unquote Collective’s Universal Child Care opens with a (literally) breathtaking sequence.

Against the gentle grey waves of a projected fetal ultrasound, six silhouetted backup singers duplicate the rapid, rhythmic breathing of a mother in labour. Downstage, that mother (Germaine Konji) prepares to deliver her baby, turning each agonized push into a soaring vocal solo. It’s a musical evocation of childbirth in which all its pain, effort and ecstasy are thrillingly intertwined. (Of course, I speak from second-hand experience.)

What follows that maternal transcendence is a powerful dose of postpartum reality.

Quote Unquote’s latest creation, presented by Canadian Stage at the Berkeley Street Theatre, is a cutting critique of child-care provisions in four of the world’s wealthiest countries. Daycare’s prohibitive costs and long waiting lists, the inadequacies and/or stigmas of parental leave, and the plight of underpaid care workers – usually women, often immigrants – are all touched upon.

At its heart is a familiar question: Why, when a child’s first five years are its most crucial, do governments and society at large still undervalue its care and penalize its parents? True, that’s not the case in all countries (think of northern Europe), but in the G8 members represented here – Canada, the U.S., Britain and Japan – progress on the issue has been painstakingly slow.

Joema Frith, left, Germaine Konji perform in Universal Child Care.Dahlia Katz/Handout

This is an angry show, but also artful and entertaining. Quote Unquote co-founders Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava, whose melding of vocal acrobatics with physical theatre first wowed us in their initial 2015 work, the since much toured (and filmed) Mouthpiece, continue to expand on their winning formula. Universal Child Care is framed as an a cappella musical, with a book by Nostbakken and Sadava and songs by Nostbakken, but based on collectively written material in the style of their last show, 2018′s Now You See Her.

The jokes, meanwhile, are provided by Mónica Garrido Huerta, who also plays the show’s wisecracking host, a self-described magical Mexican nanny – “like Mary Poppins, but cheaper.” Much of her humour has that sort of bitter edge and, indeed, there isn’t a lot to laugh at here.

We meet a single mother in Tokyo (Takako Segawa) trying to support herself but trapped in a bureaucratic loophole, where she can’t access daycare because her estranged husband won’t divorce her. Then there’s the queer mixed-race couple in London (Fiona Sauder and Anika Venkatesh) who want to have a second child but can’t afford child care that, like most everything in the British capital, is insanely expensive.

In Canada, Sadava’s working mom on maternity leave finds her job pulled out from under her – one of the 18 per cent of parents who experience that, according to the statistics that flash by in supertitles throughout the show. But she’s comparatively lucky. Here’s another fast fact: The U.S. is the only industrialized country that doesn’t offer paid parental leave. As a result, a young Detroit couple (Konji and Joema Frith) struggle to make ends meet on a single income in a precarious economy.

The only consolation are the children themselves and Frith has a lovely song in which he expresses the rapturous joy of becoming a father. It’s just one of the memorable numbers in Nostbakken’s playfully protean score. Sauder, in a marathon, rapid-fire rap, traces the long, frustrating history of attempts to establish a universal child-care policy. Sadava croons a sultry jazz ballad about the mixed messages young women receive in a still-gender-biased society. Garrido Huerta’s nanny sings a sad folk song about her own little girls, left behind in Mexico while she makes a living caring for other people’s children.

There are some beautiful voices, too. Venkatesh, in particular, thrills us with an operatic aria – perhaps the first sung by a diva while she expresses milk with a breast pump.

The cast of Universal Child Care perform on the two-storey set, which is divided into four boxes for each parental unit represented by the play.Dahlia Katz/Handout

Nostbakken’s direction is as multifaceted as her music, making imaginative use of a two-storey set, designed by Lorenzo Savoini and Michelle Tracey, divided into four boxes for each parental unit. André du Toit’s fluid lighting and the projections, by the potatoCakes_digital company, are a visual treat – even if all those passing statistics can be as overwhelming as a high-speed PowerPoint presentation. One that stuck with me: In Japan, 70 per cent of a single woman’s salary goes to child care. (And Japanese politicians wonder why the country’s birthrate is steadily dropping.)

The babies here are represented by glowing balls that are cradled, cuddled, passed around. At one point, the performers themselves become children, clambering over the set like kids in a playground. Not surprisingly, the lone white boy (Alex Samaras) ends up as the smug king of the castle. The show’s clever choreography is by Orian Michaeli.

For those of us who are parents, Universal Child Care is often preaching to the choir. Indeed, there ought to be trigger warning for one comic scene, in which Garrido Huerta’s superhuman care worker suddenly calls in sick and the rest of the cast swarms the audience, glowing-ball babies in their arms, desperately looking for last-minute babysitters. It may induce an all-too-familiar feeling of panic.

You might wonder, too, how relevant this show is for Canadians now that we finally have a national child-care program. But that doesn’t resolve the larger social issues addressed here, including the continued lack of gender parity and the exploitation of immigrant labour. This is an important piece of theatre and you should see it – if you can get a babysitter.

In the interest of consistency across all critics’ reviews, The Globe has eliminated its star-rating system in film and theatre to align with coverage of music, books, visual arts and dance. Instead, works of excellence will be noted with a critic’s pick designation across all coverage. (Television reviews, typically based on an incomplete season, are exempt.)