Tracy Robinson would be the first to admit she was a surprise choice for CEO of Canadian National Railway. She’d stepped away from the industry for close to eight years before taking over CN in February 2022. Sure, she’d spent nearly three decades at Canadian Pacific before that, with roles in sales, marketing and finance, but the investor and analyst community didn’t see her as an “operations person.”

There is, after all, a kind of mythos around railroaders. The men who lead Canada’s railroads—and they’ve all been men—have typically spent decades working with trains, prone to telling tales of the grit involved in keeping them rolling. Hunter Harrison, who’s credited with turning around several railroads, including CN, got his start as a teenage carman-oiler. Keith Creel, the Harrison disciple who now heads Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC), once trekked to a hotel in the dark of night to turn over rooms so a rail crew could sleep.

Robinson had never been an operations chief in an industry whose entire raison d’être is moving stuff from one place to another, not to mention that CN in particular was grappling with operational problems. Plus, as one analyst noted when her appointment was announced, for some of her 27 years at CP, it underperformed so badly it could only be righted by (who else?) Harrison. So how, analysts asked, was the company confident that Robinson was the right choice?

Today, the question elicits a wry chuckle. “I don’t blame anybody for having some questions,” she says. The skepticism didn’t rattle her. “I’d rather come in and show than talk,” she says. “I don’t mind having to prove it.”

And she’s made a lot of progress.

Editor’s Note: For every step forward, it seems women take two back

Innovator of the Year: Hopper’s Fred Lalonde went from hacker to tech titan

Since Robinson joined CN close to two years ago, she has retooled its operating model, whittled down its operating ratio (a crucial efficiency metric), closely integrated departments, restored credibility with key investors and won plaudits from analysts. She has done so without slashing jobs and cutting costs—a tactic so common among CEOs looking to juice results that it’s basically animal instinct—but by playing to the organization’s strengths.

What’s more, she has managed to keep at bay TCI Fund Management, CN’s second-largest investor, which waged a vicious campaign to oust her predecessor. Earlier this year, Robinson was in London to be interviewed on stage by Chris Hohn, the hedge fund’s founder, at TCI’s annual meeting.

“The things he wants are the same things all our shareholders want,” she says. “I would say we’re very aligned.” TCI partner Ben Walker said over email that the fund isn’t giving interviews, “but we do think Tracy is doing a good job.” Coming from an investor with a history of issuing bombastic statements to tear down weak executives, that may well qualify as high praise.

There’s still more to do, however. Profit has trended down in recent quarters, and the stock price is below where it was when Robinson joined. She has a stronger and wilier competitor in CPKC, whose blockbuster merger closed this year. And then there’s the weakening economy, which prompted Robinson to cut CN’s outlook earlier this year.

The initial skepticism may have waned, but Robinson isn’t done proving herself just yet.

Since Robinson joined CN, she has retooled its operating model, and whittled down its operating ratio – a crucial efficiency metric.

One skill Robinson has had to work on is her French. Headquartered in Montreal and subject to the federal Official Languages Act, CN stoked some ire last year because it didn’t have a single francophone board member, which it soon rectified. Robinson has been working with a private tutor and plugs away at Duolingo. Around CN, she speaks French with employees when she can. “It’s so far from perfect it’s not even funny,” she says, “but they appreciate the show of respect.”

On a recent visit to Taschereau Yard, not far from Montreal’s Trudeau airport, Robinson was personable and curious as she chatted (en anglais) with employees. Later, at a repair shop, she gamely joked with a group of francophone workers about the need to move trains “plus vite,” though another employee translated at times. Still, she was unfailingly enthusiastic, impervious to any awkwardness caused by the language barrier. (Maybe that’s not surprising, given her hobbies lean adventurous. The previous weekend, she went skydiving.)

There wasn’t much French spoken where Robinson grew up, outside tiny Bethune, Sask., where her family ran a farm. Her career plan was to become a phys ed teacher, but facing slim employment prospects, she completed a business degree at the University of Saskatchewan before getting recruited by CP on campus. She was flown to Vancouver, Calgary and Montreal for interviews, and had visions of a big-city job. Instead, she was offered a sales position in Regina.

After plenty of heated debate between editors and reporters from across The Globe and Mail, these are the top five executives across the Canadian business landscape that deserve to be celebrated for their outstanding achievements.

The Globe and Mail

Robinson started cold-calling prospects, sometimes heading out to warehouses to sway companies that shipped by truck to switch to rail. She had a knack for it, and over the next couple of decades, she took on a variety of roles in Calgary, Vancouver, Edmonton and Montreal, from marketing, strategy and operations to customer service and finance. She also served as chief of staff to former CEO Rob Ritchie. “You could have five different careers in the same company, and there weren’t a lot of people going across functions,” she says, adding she had no grand career plan. “I was curious, always, around how the next thing got done.”

She came to see herself as a utility player, someone who could learn and adapt regardless of the role. Robinson, who also earned an MBA from the Wharton School of Business, was appointed vice-president of marketing and sales in 2010. In that position, she struck up a conversation with TC Energy (then known as TransCanada) about shipping crude oil by rail, owing to the difficulties the company faced with its cross-border Keystone XL project. Instead, she left CP in 2014 to join TC.

Robinson spent seven years there, most recently as head of Canadian Natural Gas Pipelines, where she gained a deeper understanding of capital expenditure. She wasn’t necessarily expecting to return to the rail industry, but then CN called.

The country’s largest railroad had run into trouble, and much of it spilled into public view through its ill-fated quest to purchase Kansas City Southern. In March 2021, CP first announced a deal to buy KCS for US$25 billion in cash and stock, a deal that would create the only railway connecting Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. CN attempted to blow up the whole thing by tabling its own bid worth US$33.7 billion, but the offer was undercut by regulatory uncertainty. The U.S. Surface Transportation Board (STB) would first have to approve CN’s proposal to create a voting trust (which would allow shareholders to be paid out quickly while a full review was completed) and said it would take a more cautious approach to reviewing the deal than it would for CP, in part because a CN-KCS merger could dampen competition.

The Globe and Mail

Everybody but CN saw that it was doomed to fail, especially TCI, which owned a more than 5% stake in CN worth US$4 billion. TCI wrote to CN’s chair to call the bid “extremely reckless” and warned the railway could face billions in liability if the deal was rejected.

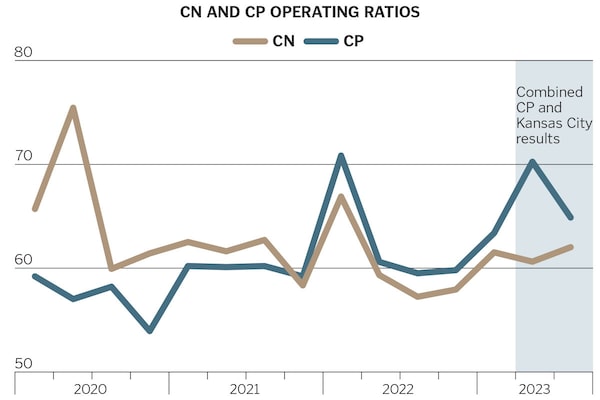

The STB did in fact reject CN’s proposal, in August 2021. By then, TCI was out for blood. The fund issued a blistering letter to the board calling out the railway for years of underperformance. “CN has lost its way, and the business needs to be fixed as a matter of urgency,” TCI wrote. Operating income, earnings per share and free cash flow had all declined under CEO Jean-Jacques Ruest, TCI charged, while noting CN’s operating ratio, which measures operating expenses as a percentage of revenue, had gone from best-in-class to worst. TCI moved to call a special shareholders’ meeting to give Ruest the boot, along with CN’s longtime chair, Robert Pace.

In January 2022, CN and TCI reached a truce. They would jointly appoint two independent directors. Ruest, whose retirement had already been announced a few months earlier, would be replaced by Robinson.

While some investors and analysts expected to see an operational CEO replace Ruest, the board was thinking more broadly, says Shauneen Bruder, CN’s current chair. The board wanted someone who could define a long-term vision, and build a culture and team to deliver on it. “Tracy just continued to rise to the top in terms of her ability to deliver across all three horizons,” says Bruder. Rather than view Robinson’s time away from the industry as a red flag, the board saw it as a virtue. “If you’ve grown up in one industry and that’s all you’ve known, you don’t consider the possibilities for different approaches.”

CN required fresh thinking. Some may quibble about the depth of its problems, but there’s no doubt the company had hit trouble. “They slipped over multiple years in terms of margin performance because of operational management not being as solid as it used to be,” says Konark Gupta, an equity research analyst at Scotiabank, adding that CP had been able to poach customer contracts. Even internally, some of TCI’s criticisms were seen as valid. “They made the point that we were lagging earnings, and that’s true,” says Ghislain Houle, CN’s CFO since 2016. “It sends the message that we’re not productive.”

What was apparent to Robinson was that CN was running the wrong model for its network. It had been seeking to reduce the number of train starts and run very, very long ones, which can save on labour and be more efficient. That works well for a railway like Burlington Northern Santa Fe in the U.S. (where CN’s previous operations chief hailed from) because it has double or even triple track in places, allowing trains to more easily pass one another. CN, however, is a single-line network. “That doesn’t work here, because you’ve got two long trains about to meet each other,” Robinson says. Without adequate siding infrastructure, where trains can pass one another, delays mount up—which happened at CN.

Robinson got in touch with Ed Harris, a five-decade industry veteran who was CN’s COO until 2007. She flew to Chicago to meet him in person, and a one-hour meeting stretched to three. “She had some concerns with what she was seeing, and I tried to answer some of her concerns with what I thought needed to be done,” Harris says. He first joined as a consultant in April 2022 and then as full-time COO in November.

On his first day back, his wife texted him a picture of a bouquet of flowers. They were from Robinson, who’d sensed that Harris returning to work in his 70s might cause tension. “That goes a long way when I open the door and come in for the day,” says Harris.

Compounding CN’s operation problems, in his view, was the fact that it had cut too many employees, including 650 managers and 400 unionized workers in the midst of its fight with TCI. “When Tracy got here, she could tell it was already cut to the bone,” Harris says. CN has since brought on 1,700 employees to replace what was lost. Cutting heads achieves little in the long run, Harris says. “What gets you something is keeping the traffic moving.” (Harris’s post was never seen as long-term, and in October, CN announced it was splitting his job between two CN executives.)

In short order, CN abandoned the strategy of waiting to build up long trains, and instead focused on running them quickly and reliably. “We still want 12,000-foot trains,” Robinson says, “but the train has got to leave on time.” That means it can move more volume with fewer cars and fewer delays. Since making the switch in April 2022, CN now has a 90% on-time departure rate compared to 79% last year, and car velocity (how many miles a car moves in a day) has improved by between 15% and 20% since her arrival. The operating ratio is down, too, from 66.9% when Robinson joined to 62% in the third quarter.

Western Canada was another problem. CN had taken on more business than it could handle, raising costs and increasing congestion. Robinson is now taking a more disciplined approach. “If we have the opportunity to sell more than we have,” she says, “we’re not going to take it on until the capacity exists.” It’s a delicate balance—CN can never be sure how much potash the world will mine or how many cars consumers will demand. “It’s not an exercise where you have great certainty,” she says.

She’s also made organizational changes to help prevent such a mismatch from happening again. The company was too siloed, impeding communication. Robinson has since instituted a meeting every two weeks for executives and direct reports to discuss customer contracts, capacity and pricing to ensure departments are aligned. She expects employees to weigh in on issues beyond their own departments, too. “She tells us clearly you’re not here to advocate your function. You’re here to give your opinion on the entire business,” says Houle.

For the most part, analysts have been impressed. Tony Hatch, an independent rail analyst in the U.S., says Robinson has pivoted the company toward growth (CN has the potential to invest $4 billion between 2024 and 2026, in part for network and tech upgrades) as opposed to ruthless cuts. “Sometimes that pendulum swings way too far,” he says. “You hit the level where you start to irritate your employees, your regulators, your legislators and, most importantly, your customers.”

The changes have also put CN in a better position to drive profitability, according to Dan Fong, an analyst at Veritas Investment Research. “They have, to my mind, righted the ship. Operationally, they’ve made all the right moves,” he says. The changes have yet to do much for CN’s stock, which was down about 5% in early November from when Robinson joined. Fong says the trend has more to do with macroeconomic uncertainty than doubt about CN. Indeed, revenue slipped 12% in the latest quarter compared to the year before due to lower volumes.

There are still more challenges, such as the newly formed CPKC, which provides an enticingly efficient route. In response, CN partnered with Union Pacific in the U.S. and Ferromex in Mexico in April to launch Falcon Premium, a service joining all three countries. CN has billed it as the most direct route between Canada and Mexico, and claims it’s faster than any other option.

Fong contends CPKC has the advantage, estimating its route is two to three days faster from Mexico to the U.S., with less complexity. “It’s going to be tough for that whole consortium to attract some of that traffic,” he says.

Robinson, as always, is aware of what she’s up against. “The challenge we have is to take three railroads and operate as one,” she says. “So far, it’s going very well, but that’s the test.”

One more thing for Robinson to prove.

Joe Castaldo

Joe Castaldo