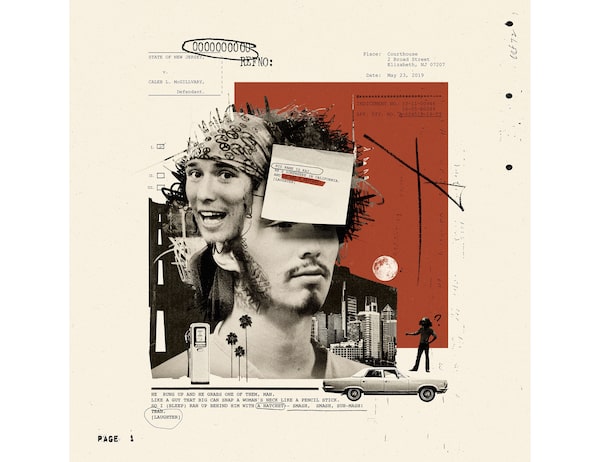

Illustration by Klawe Rzeczy. Sources: Patti Sapone/NJ Advance Media via AP, Pool; Jessob Reisbeck/YouTube; court documents from the State of New Jersey; television transcript from The Colbert Report

Meeting Jesus on the Highway

It was late in the morning on Feb. 1, 2013, when Caleb Lawrence McGillivary met Jesus Christ on a highway outside Bakersfield.

McGillivary had been on the road a good while by then, having left his home in Alberta as a teenager to find his own way in the world. He’d gone back at times, back to his family, back to school or work, but that kind of routine never suited him for long, and by the early months of 2013, he was drifting once again. Not homeless, he would tell people. Home free.

He’d hitchhiked through provinces and states, walked over mountains and across borders. He moved as the mood took him, sleeping under bridges and in vans and on boats and couches, working when he had to, finding friends and parties and beaches to surf along the way.

He called himself Kai, unless the authorities were asking, in which case he was Edward Carl Nicodemus or whatever other series of monikers might come to mind. He was 24 years old. The road had turned him lean and luminous, burnished golden by dirt and sun.

He spent the last night of March sleeping alongside Route 99 in California, the road heading north toward Fresno. He was standing beside the highway when a black Oldsmobile rolled to a stop, and the driver beckoned him inside.

On that morning, Jett Simmons McBride was on his way to thwart a terrorist attack he believed, from conspiracy theories he read on the Internet and his own calculation of numbers and signs, was about to occur at the Super Bowl. He was 54, well over six feet tall and almost 300 pounds, with a thin bow of a mouth and pillowy bags under his eyes. He’d barely slept or eaten for weeks, and had recently come to the conclusion he was Jesus Christ.

McBride had thrown away his cellphone and left his dog, Zoe, on the side of the road so neither could be used to trace him. When his phone was found and returned, he smashed it and threw it away again. He was doing his best to ignore the white trucks he knew were members of the Illuminati following him.

Then he saw the hitchhiker.

Everything was fine between them on the way to Fresno. They talked about God and Walmart and numerology, and when they got to the city, McBride gave McGillivary $40 to buy pot. The car was overheating, so they smoked a joint while McGillivary poured water into the radiator until it was ready to go again.

Even after everything that happened in the minutes that followed, McBride would still say Kai was the coolest son-of-a-bitch he ever met. If things had gone differently, he said he could have imagined adopting him like a son.

Watch: McGillivary gives Fox affiliate KMPH a strange account of the events on the Fresno highway.

Straight Outta Dogtown

Jessob Reisbeck was an experienced reporter at KMPH, the local Fox-affiliate TV station in Fresno, but he typically covered sports, and had only recently started filling in on other stories. The call that came through the scanners that Friday afternoon was his first breaking news assignment.

He arrived at a chaotic scene. A man had steered his car into a group of Pacific Gas & Electric workers, throwing one several feet and pinning another against a truck. Witnesses described the man, who would later be identified as Jett Simmons McBride, emerging from the car screaming “I’m Jesus Christ!” yelling death threats and racial slurs.

McBride had tried to yank the crushed worker from between the vehicles, tugging at him until a former nurse who had been across the street ran over and wedged herself between them, trying to protect the injured man.

Witnesses said McBride then grabbed the woman in a bear hug, and was kissing and hitting her when a young man ran toward them with something that looked like a hammer.

Reisbeck was still talking to a witness when he spotted the young man walking nonchalantly across the street. The reporter ran over to catch him. “Are you the hero?” he asked, reaching out his KMPH News microphone.

“I’m one of the heroes,” McGillivary said.

He wore a red sweatshirt and carried a hikers’ backpack, and a bandana printed with peace-signs constrained a tangle of sun-bleached hair. He held a cigarette, with another tucked up by his right ear.

“What happened today?” Reisbeck asked.

“Well, it went straight out of Dogtown,” McGillivary said.

Then he stopped and turned to the camera.

“Before I say anything else, I want to say no matter what you done, you deserve respect,” he said. He looking straight into the lens, his eyes searching and earnest.

“Even if you make mistakes, you lovable. And it doesn’t matter your looks, skills or age, your size, or anything, you’re worthwhile. No one can ever take that away from you.”

Then he turned back to the reporter, and continued the story.

He said McBride had driven intentionally into the workers, and that he’d taken the keys out of the car so McBride couldn’t move it and hurt the pinned worker further, or harm anyone else. He described seeing McBride grab the woman.

“A man that big can snap a woman’s neck like a pencil stick,” he said.

He said he ran up behind McBride with a hatchet, and pantomimed lifting it above his head, then bringing it down. “Smash, smash, suh-mash.”

He said his name was Kai – “Straight outta Dogtown. K-A-I” – but offered little else. Asked his age, he said, “I can’t call it.” Asked where he was from, he said “Sophia, West Virginia,” with a sly wink that showed it wasn’t true.

When Reisbeck asked if he had a last name, Kai smiled and said, “No, bro. I don’t have anything.”

Driving back to the station, Reisbeck replayed the interview in his mind, trying to make sense of the scene, and of the man he’d just met. It was like nothing he’d ever experienced.

The interview went online that night, and Reisbeck awoke the next morning to a flood of emails and texts. “Bro, you’re blowing up,” his brother told him.

Kai the Hatchet-Wielding Hitchhiker had been born.

Watch: McGillivary’s Fox interview gets a musical auto-tune treatment.

‘Smash smash smash’

It was a strange thing to go viral. The interview was long, nearly six minutes, and though McGillivary could be charming and funny, the story itself was not. A mentally ill man had driven his car into a group of people while screaming racial slurs. The worker who had been crushed was very seriously injured, and McGillivary had hit the attacker repeatedly in the head with a hatchet. While people particularly loved the “smash smash smash” part of the interview, it wasn’t even clear from the footage McBride had survived. (He had.)

Some of the things McGillivary talked about were violent and sad. He said McBride admitted to once raping a girl in the Virgin Islands, and he showed deep scars on his knuckles he said were from another time he’d beaten someone while trying to protect a woman.

“You see all these teeth marks right here?” McGillivary asked, holding the back of his hand up for the camera. As he spoke, his expression slid between amusement, anger and sorrow, and back again.

Still, something about it connected with people.

Maybe it was his colourful language or his wild and carefree vibe, or the idea of such an unlikely hero in such a troubled time. Maybe it was how, when he said that everyone deserves love and respect, it felt like he was speaking right to you.

A video posted by the cameraman was viewed 400,000 times overnight, and versions by the station and Reisbeck – and by others who appropriated it for profit on their own YouTube and social media channels – were racking up thousands, and then millions, of views within hours. One man got five million views on the video in barely more than a day, before the station ordered him to take it down.

McGillivary himself was a mystery. He hadn’t spoken with any other reporters at the scene, and he had no phone, no address, and hadn’t given out his real name or where he was from. The only known contact was Reisbeck, who had his e-mail address. At some points, Reisbeck was getting dozens of messages every minute, all from people looking for Kai.

The video spread quickly across the state and across the country and across the world, until it reached northern Alberta, where it was shared between McGillivary’s siblings and parents initially as just another dispatch from his travels, with notes that said: “If you’re curious what Caleb is up to …”

They had seen him at a wedding in Red Deer a few months earlier, and it just seemed so Caleb for him to suddenly reappear like this. It didn’t surprise them at all that he’d been helping people. But it was also clear he’d been through something traumatic. As his mother watched people’s reactions – and saw the reach of the video continue to spread and grow – she grew increasingly disturbed.

McGillivary’s teenaged sister saw her friends post and repost the video, having no idea Kai was her brother. It didn’t seem funny to her at all.

At one point in the interview, he said, “I don’t have any family. As far as anybody I grew up with is concerned, I’m already dead,” and it hurt to hear that. Things hadn’t always been easy between them, but it upset his mother that he seemed to think they didn’t care.

McGillivary spent his early life in Red Deer, and his family later moved to St. Paul, about two hours’ drive northeast of Edmonton. He was the second of four children, and held treaty status with the Opaskwayak Cree Nation in Manitoba. (His last name has appeared in news coverage and on court documents with the spelling “McGillvary,” but his mother, Shirley Stromberg, says McGillivary is the correct spelling and that is the spelling his birth father uses.)

He’d always been remarkably smart and creative, full of energy and fire. But he struggled throughout his life, and had been hospitalized more than once for mental health treatment. As a teenager, he had been devastated by a serious sexual assault he suffered while hitchhiking through B.C., for which a man was charged but not convicted.

By his late teens, McGillivary spoke three languages and had done some schooling, but he was always drawn back to the road, and his family let him go. As his younger sister would say, “One of the things with loving a free spirit is understanding that you’ve got to let them be a free spirit.”

In California, Jessob Reisbeck e-mailed McGillivary to tell him the interview was going viral, and not to be surprised if people started recognizing him on the street. By the time the two met to film a follow-up story, Reisbeck had become the de facto contact between McGillivary and the throngs of people trying to get in touch.

In some ways, Reisbeck was worried about McGillivary. McGillivary was obviously highly intelligent and street smart, but there was also something about him that seemed vulnerable, and Reisbeck wanted to protect him. It suddenly felt like everyone in the world was trying to get to Kai.

Soon there were invitations to 13 different countries, and just about every news program and talk show imaginable. The most notable interest, Reisbeck says, came from the producers of Keeping Up With the Kardashians, who wanted to do a reality show.

Three or four days after the viral video, Reisbeck and McGillivary met at a fast-food restaurant in San Jose. McGillivary scarfed down a pile of burgers and fries while Reisbeck laid out the offers. Fame, money, celebrity. The American dream glimmering there before him, conjured by six minutes of viral video.

McGillivary listened, then threw a pencil in the air. “If it landed one way, he was going to go and potentially make millions of dollars … He was going to be a reality TV show star,” Reisbeck says. “Or, he was going to go smoke weed in San Francisco.”

When the pencil fell to the table, McGillivary said, “Well, I’m going to go smoke weed.’”

But Reisbeck says the producers pushed hard for at least an appearance on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, sweetening the deal by promising to put McGillivary in a limo filled with weed and let him drive him around LA doing whatever he wanted. This time, when Reisbeck passed along the offer, McGillivary said yes.

Watch: McGillivary joins TV host Jimmy Kimmel for a sketch showing the two of them behind the dashboard of a car.

‘When we come back from commercial, the hatchet man himself, Kai, will be here’

JIMMY KIMMEL: Ladies and gentlemen, please say hi to Kai. Kai! Jump in the car.

AUDIENCE CHEERS, KIMMEL WELCOMES KAI

KIMMEL: You’ve become very famous now from YouTube, haven’t you? I mean, people are recognizing you? What do people say to you when they see you?

KAI: They say, “Hey, you’re Kai. You’re that dude with the hatchet.”

It was Feb. 11, 2013, 10 days into McGillivary’s viral fame, and he was on one of the most popular talk shows in the world. He sat beside Kimmel in the passenger seat of a set car, the studio audience roaring with laughter as McGillivary answered questions about his life and philosophies, and described his plans to build a house of willow hoops and moss.

“You don’t want to have a home, correct?” Kimmel asked.

“What the hell are you talking about?” McGillivary said. “I am home.”

At the end of the appearance, Kimmel gave McGillivary a surfboard and a wet suit, and they hugged.

“Thanks for not killing me with a hatchet,” Kimmel said.

By then, there were Kai memes and Kai gifs, Kai Facebook fan pages, and a flurry of Twitter accounts like @DogtownKai, @HatchetGuyKai and @NotTheFakeKai. There were “Kai the hitchhiker” buttons and posters and T-shirts for sale, and, it being February, Valentines that read “I must ax you a question” and “Don’t Smash Smash Su-mash my heart.” One woman knitted his likeness in the form of tiny, hatchet-wielding doll.

Suddenly everyone who ran into McGillivary wanted to get him stoned or buy him a drink or a meal, a small price for a selfie and a story to share on their own social media pages. “How many nights should I offer my couch to Kai for?” one man asked in a Facebook poll. “He’s kinda famous.”

The original video was repeatedly transformed and remixed, including by The Gregory Brothers, best known for their wildly popular "Bed Intruder Song" which set to music an interview with a man describing a home invasion and the attempted rape of his sister.

On The Colbert Report, Stephen Colbert concluded, “For the first time in human history, people are saying, ‘Boy, we sure are lucky that homeless hitchhiker was carrying a hatchet.'”

But McGillivary was not always who people wanted him to be. The things that made him stand out in the viral news video – his unpredictability, his irreverence, his audacity – could be maddening in real life.

In the resort towns of B.C., where McGillivary had lived on and off, people remembered him as outgoing enough to sit down at a table full of strangers, but so unruly he’d been kicked out of “every drinking establishment in this town.” As Reisbeck quickly learned, McGillivary was impossible to control or predict, and there was something in him that could turn suddenly dark, like a switch had been flipped. He could be extremely kind and generous, and a moment later, equally crude and profane.

In California, McGillivary rode his skateboard through the lobby of the Roosevelt Hotel, and out for a fancy lunch with the TV executives, smashed a plate on the floor and yelled “Opa!” He urinated on Julio Iglesias’s star on The Hollywood Walk of Fame, then left the backpack with everything he owned outside the hotel for someone else to take, telling Reisbeck: “Look where I’m staying tonight. Someone definitely needs that more than me.”

Before the Jimmy Kimmel appearance, McGillivary urinated on a sign for the show, then gave the money he got from Kimmel to a security guard in apology.

“You don’t understand what it’s like to hang out with this guy,” Reisbeck would tell people then. “You’re trying to keep him out of trouble, you’re trying to keep an eye on him, and you’re trying to keep yourself out of trouble because he does things that are just off the wall. He completely lives by the beat of his own drum.”

Sometimes, Reisbeck wondered about McGillivary’s mental health. Where is the line between uninhibited and unbalanced?

Weeks later, as he drifted from place to place on a wave of viral celebrity, McGillivary got a large tattoo on the right side of his face and neck. One website held a contest to identify the images, describing it as “a swirling miasma of mystical symbolism perfectly befitting a man of Kai’s guru-like qualities.”

But public attention and interest was already starting to turn. While some commenters defended the tattoo, others concluded McGillivary was stupid or high or mentally ill or just seeking attention. By the end of March, a Facebook page that had been formed in his honour and hosting concerts and events with him in Fresno was shutting down, a terse message announcing “WE CANNOT VOUCH FOR KAI’S INTEGRITY TOWARDS PEOPLE ANYMORE.”

“Kai has worn out his welcome in Fresno to people's kind hearts and good graces,” one of the page’s administrators wrote. Among the issues sited were “constantly cussing in front of children with no remorse,” “blatant DISRESPECT towards women,” and offending musicians “by lack of respect for time.”

“We hope Kai will help himself and best wishes to him. LESSON: DISRESPECT and UN APPRECIATION WILL GET YOU NOWHERE! You're not going to come into OUR city and THINK you can RUN OVER us with your so-called FAME!””

People responded with emojis that showed tears of sadness and tears of laughter, and gifs of McGillivary smash-smash-smashing. “Kai was fun for his fifteen minutes of fame,” wrote one woman. “And then he became old before his time!”

McGillivary's trippy face tattoo was met with some ridicule from his supporters on Facebook. But then, online exchanges with his supporters began to take a darker turn.Courtesy of Damen Tesch and Second Sight Tattoo/Handout

‘Dude … Wtf? U serious?’

On Tuesday, May 14, 2013, about 3 ½ months after the viral video, a disquieting post appeared on McGillivary’s personal Facebook page, seemingly written by him.

“what would you do if you woke up with a groggy head, metallic taste in your mouth, in a strangers house...,” it read.

What if you realized you had been drugged and sexually assaulted? the post asked. What would you do?

“Find them as fast as I could and SUH-MASH … them with a hatchet or whatever else I could find!!,” responded Terry Ratliff, a Facebook friend who had become acquainted with McGillivary after doing a musical remix of the news interview.

McGillivary responded, “i like your idea.”

It was hard to know what to make of the post. McGillivary sometimes posted things that were disturbing and dark, and it could be difficult to tell whether or not he was serious, or even what he was talking about. Ratliff – who also asked, “Dude … Wtf? U serious?” – says he thought it was some kind of symbolism.

McGillivary had recently written about wanting to be in a porno film where the profits would go to “a civil rights group that aims to arm single mothers in poverty stricken areas with shotguns.” Another post described wanting to “smash smash smash” the leader of North Korea “DEAD,” and, more explicitly “beat him to death with a hammer.”

Days earlier, McGillivary had written a long and detailed post saying he was sexually and physically abused and locked in a cage as a child, and that his family were members of a cult who believed there was a demon in him.

The reporter Jessob Reisbeck was among those who saw the post about waking up in a stranger’s house, and he, too, wondered what to make of it.

He knew McGillivary had a history of sexual abuse and trauma. In their interview for the follow-up story Getting to Know Kai: The Truth Behind The Hero, McGillivary recounted experiences Reisbeck described in the segment as “darker and more gut-wrenching than you can imagine.”

That conversation, and the other time they’d spent together, made it clear to Reisbeck that McGillivary had some “dark places,” and a particular animosity for people who take advantage of others. His moods could change quickly and drastically. Reisbeck knew if someone got into McGillivary’s space or if he even felt they overstepped, things could go very badly.

McGillivary sometimes talked about being a vigilante and going after pedophiles. In an interview with a California radio station in April. McGillivary talked about being sexually assaulted as a teenager. “I realized I’d never let something like that happen to me again,” he said then. “I’d rather die than let something like that happen to me again.”

‘Do you think Kai is a victim of poor timing or a crazy killer?’

Joseph Galfy Jr. is shown in 2011, two years before he met McGillivary.Facebook/Facebook

Joseph Galfy Jr. met the young man who called himself Lawrence Kai in Times Square on a Saturday afternoon in May. It was the day before Mother’s Day, 2013. Galfy was 73 years old, a lawyer and former military man who was well-known and respected in the close-knit community of Clark, New Jersey.

“You look lost,” McGillivary would remember him saying.

They left New York together in Galfy’s car, and headed to his tidy suburban home. On the way, Galfy picked up food and a pack of Newports. He offered McGillivary beer and a place to stay.

"You need to be very careful, Kai," texted Kim Conley, a Facebook friend who had planned to meet up with McGillivary that weekend.

"Im carefree and brave ill be fine,” McGillivary assured her. “I found a good person who put me up for the night."

McGillivary left Galfy’s house the next morning, then returned again that night.

When Joseph Galfy didn’t show up for work on Monday and missed an appointment, his paralegal called some of his friends and neighbours, and asked them to check on him.

Robert Ellenport, the former mayor of Clark and a long-time friend of Galfy’s, arrived to find the bungalow at 46 Starlite Drive dark and quiet. The day’s New York Times sat uncollected outside.

Galfy had heart problems and other health issues. He’d lived alone since the death of the man some knew as his “houseboy and employee,” and others, like Ellenport, understood to be his partner, several years earlier.

Given Galfy’s age and health, Ellenport expected the worst when a police officer who responded to the scene emerged from the house looking grim. But Ellenport was speechless when he learned his friend had been murdered. He would be further shocked to discover the suspect was a man he recognized from a bizarre news story earlier a few months earlier.

McGillivary was arrested three days later in a Greyhound station in Philadelphia. He’d chopped his long hair short with a knife, but had still been recognized by multiple people, both because of his internet fame and the distinctive tattoo on his face.

When the officer tapped him on the shoulder, McGillivary initially thought it was a fan, seeking an autograph.

“Being on YouTube too much is not always a good thing,” noted Philadelphia Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey, after the arrest.

Joseph Galfy had been found facedown on the floor of his bedroom dressed only in his underwear and socks. He’d been brutally beaten, with fractures in his the bones of his face, neck and ribs, and bleeding in his brain. One of his ears had been torn almost off.

Police connected the two men through texts on Galfy’s phone.

It was a sensational afterward to the original story. Headlines and chyrons blared ‘Hatchet Hitchhiker Arrested For Murder’ and ‘Kai a Killer?’

One video, entitled “Kai the hatchet wielding hitchhiker hero may actually be a murderer,” reenacted the events in a gleefully gory animation. “Do you think Kai is a victim of poor timing or a crazy killer?” the narrator asked at the end. “Let us know in the comments!”

McGillivary talks to the media as he is taken by Union County sheriff's officers to jail in Elizabeth, N.J., on May 30, 2013.Mel Evans/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

‘He may be crafty, shrewd, manipulative, et cetera’

The trial began in New Jersey in April 2019. McGillivary had been held in jail for six years by then, much of it in solitary confinement or segregation. He had attempted suicide at least once.

He appeared on the first day of court in a dark suit and tie, dark hair hanging loose past his shoulders. A heavy chain bound his ankles.

McGillivary’s celebrity outside the courtroom was, if anything, a liability inside it. Before the trial began, Union County Superior Court Judge Robert Kirsch denied requests by Court TV and Inside Edition to broadcast the proceedings, and further barred mention of any kind of Internet fame during the trial – including the “notorious expletive-ridden video interview” – which he said was for McGillivary’s own good.

“It is obvious that he plays to the media. He’s obsessed with it,” the judge said in court. “I’ve never seen anything quite like it, quite honestly, and for his own sake, I am removing that intoxicant to him so that he can focus on the matters at hand.”

Whenever McGillivary got close to mentioning the viral video or obliquely referenced his Internet fame during the trial, Kirsch immediately shut it down.

Though court heard McGillivary had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, his lawyer said McGillivary didn’t want his mental health to be considered as a defence, except for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder related to his assault as a teen.

Judge Kirsch agreed McGillivary’s fitness to stand trial was not an issue, saying: “He may be difficult. He may be obstructive. He may be disingenuous. He may be crafty, shrewd, manipulative, et cetera, but he is quite clearly competent.”

Kirsch also denied McGillivary’s request to fire his lawyer and represent himself.

Testifying in his own defence, McGillivary repeated what he’d told the police immediately after his arrest: That he blacked out after drinking a beer both nights he spent with Galfy, and awoke on the Sunday night to find Galfy on top of him, pulling his pants down and trying to sexually assault him.

He said he only fought to get away, and didn’t know Galfy was dead until after he was arrested.

McGillivary’s lawyer raised questions about the police investigation, including why drinking glasses in the home weren’t examined for drug residue, why blood in a semen swab taken from Galfy’s body wasn’t tested for DNA, and why police didn’t perform a rape kit on McGillivary after his arrest.

Throughout the trial, McGillivary sometimes interrupted with his own legal arguments and comments, at times so disruptively that the judge threatened to remove him from the courtroom. One reporter noted that, McGillivary’s “eccentric facial expressions and constant eyebrow raising were reminiscent of the YouTube video that made him Internet famous.”

McGillivary implied and, at times, flatly alleged, collusion and corruption among the police, lawyers and judge. He noted that the prosecutor repeatedly referred to the victim casually as “Joe,” as though they were friends.

When jurors were chosen, they’d been polled about their taste in television shows, and the judge warned real life cases often fit no such easy narratives.

If the jury believed McGillivary killed Galfy while defending himself, they could find him not-guilty. They could also convict him of a lesser offence, such as manslaughter, which would recognize an act committed in the heat of passion or after a provocation.

The jurors deliberated for two days. In that time, they came back with one question, about manslaughter. But when they returned a verdict, it was first-degree murder.

On May 30, 2019, Kirsch sentenced McGillivary to 57 years in prison. “You created this public image of a surfing free spirit, unshackled by the constraints of materialism and consumption. But underneath that free spirit, the jury saw another side of you …” Kirsch said, during his sentencing. “You are a powder keg of explosive rage, a cold-blooded, calculated, callous killer.”

He noted McGillivary will be eligible for parole around 2061, when he is about 72 or 73 years old. “Which, by complete coincidence is still younger than Mr. Galfy was when you murdered him.”

Given a chance to speak, McGillivary said he had been wrongfully convicted by a system both corrupt and stacked against him. "This has been nothing but a sham trial, and you have railroaded an innocent man,” he said. “Shame on you.”

McGillivary is arraigned on murder charges in Elizabeth, N.J., on June 3, 2013.Star Ledger, Patti Sapone/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

#FREEKAI

For a time, there was a rush of people wanting to help. There were donations for bail and a lawyer, pledges of support, hashtags like #FREEKAI and #INNOCENT.

Terry Ratliff, who launched the first efforts to raise money after his arrest, says he felt sorry for McGillivary, especially if things happened the way McGillivary said they did.

But the community supporting McGillivary was knotted with infighting. Some supporters were “obsessed,” Ratliff says, and others encountered floods of harassment from online trolls.

The public’s attention waned as time stretched on in the years before trial, and others drifted away as the evidence started to come out. At some point Ratliff says he, too, stepped back, realizing that “there was obviously more to the story than we knew.” He could no longer say for certain whether Joseph Galfy had been killed in self-defence.

“In my mind state at the time, I thought it was a good cause... I thought I was helping do some right,” he says. “Was I wrong? I very well could have been wrong, but I did cleanse my hands of it.”

He says he now prefers to keep his opinions on the whole situation to himself. “We weren’t there,” he says.

A psychological report filed with the court described McGillivary displaying “serious anti-social behavior” from the time he was a toddler, and said he admitted to killing hamsters and trying to set the family home on fire as a child.

In interviews, McGillivary’s mother, Shirley Stromberg, did not want to speak about her son’s mental health, except to say he struggled with his parents’ divorce and then with the sexual assault he suffered as a teen, and that there were times in his childhood and youth when he was “not necessarily having the ability to make good healthy decisions.”

“Being a free spirit is not a mental health issue,” she said. “Because somebody doesn’t fit into a box isn’t a mental health issue.”

She didn’t want to talk about the allegations of abuse he’s levelled against her and her family, except to say they got help as a family to be healthy.

“This is about him, and this is about the rest of his life,” she said. “And that’s really the thing that I focus on the most.”

She said she and her son are not currently in contact, and that she didn’t attend the trial based on his wishes.

Before the verdict, some of the family took surfing lessons at the wave pool in West Edmonton Mall, hoping to feel connected to him by doing something he loved.

“He is so much more than Kai the hatchet hitchhiker,” his sister says. “That’s something I wish I could scream at the world sometimes.”

While McGillivary was awaiting trial, Jett Simmons McBride faced his own charges of attempted murder, assault with a deadly weapon and battery for the car attack. He was committed to a state mental hospital for a maximum of nine years.

Watch: In the summer of 2012, before his viral fame, McGillivary stopped to play the ukulele on this beach in Vernon, B.C. The song was Wagon Wheel, a story of wandering across America, originally co-written by Bob Dylan and Ketch Secor of the band Old Crow Medicine Show. ‘if I die in Raleigh at least I will die free,’ he sings.

‘YouTube: Kai The Hatchet Wielding Guy Plays Wagon Wheel on Green Ukulele’

The man who was once called Kai the Hatchet-Wielding Hitchhiker is now inmate #1222665 at New Jersey State Prison, a maximum-security prison for dangerous and violent offenders.

He spent the past year working to overturn both his conviction and sentence, with the help of a paralegal who has been volunteering her services after coming across his viral video online. An appeal brief was filed in April.

McGillivary is now 31. In interviews and messages, he says he spends his days in his cell reading, doing yoga and meditating for hours on end, looking out to the universe from within steel bars and concrete, sharp curls of razor wire. He says he is given time outdoors once every five days.

On the Kai the Hitchhiker Legal Support Page, people still share words of support, sending him love, light and prayers, and sometimes, money for his commissary and his legal fund. There was a petition to Netflix to make a documentary, in the hopes that more publicity on the case will help.

Many of the other fan pages and fundraisers are gone, withering into a collection of dead links and old stories, replaced by new celebrities and new causes, new heroes and villains, new stories that may or may not quite fit the narratives we want them to.

“The internet created this whole sensational story, and the real life tragedy got lost,” says Joseph Galfy’s friend, Robert Ellenport. He says his friend’s death did not get the attention it deserved, because of the broader spectacle. “The Internet burst lasted a short period of time, and the tragedy and sorrow continues.”

Online, pieces of the story remain frozen in time, moments preserved and ready to be played and replayed. To be watched and liked and shared and commented on.

There is McGillivary as a hero, saying that no matter what you’ve done, you deserve respect and love. There is McGillivary on a talk show, talking about building a house of branches. There is McGillivary shirtless on a beach, singing a song about living on the road and dying free.

Sometimes, his supporters post a note or recording online, a message from Kai for anyone who might still be out there, listening.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Jana G. Pruden

Jana G. Pruden