Illustration by Raz Latif

First Person is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

The gravel road stretched out endlessly in front of us as my father and I sped along the Dempster Highway under the tempered Arctic sun. We were mere hours away from Tuktoyaktuk, our final destination after weeks of driving, where the road gives way to the Arctic Ocean. This road trip from Ottawa to Tuktoyaktuk – thousands of kilometres, the boreal forest and the tundra unfolding in front of us – promised to be our crowning adventure. But up until a few days before we were set to leave, I wasn’t sure we would make it at all.

For as long as I can remember, driving has been an immutable, elemental part of my father’s nature. He was always on the go, and the old adage “life is about the journey, not the destination” wasn’t strictly true – for my dad it wasn’t so much about the going, but more the getting there that mattered. And if my father was eternally in the driver’s seat, then I was always along for the ride. First, as a reluctant tagalong who had no choice in the matter: it was his way or the highway (and usually both). Then eventually I was there because I wanted to be. I chalked it up to Stockholm Syndrome or genetics.

But as we excitedly plotted and planned our route up north, my father’s health was wavering. Fifteen years earlier, my dad had been diagnosed with cancer and given a year to live. After a decade and a half, a handful of hospital stays, two rounds of chemo and one life-saving clinical trial, he had fomented his identity as someone who beat the odds. Leukemia, though chronic, had become a condition my father managed, like taking his car in for tune-ups. Through it all, we had hardly missed one of our annual summer road trips.

Days before we were set to leave, I conferred with family members over the phone, panicking privately about the prospect of Dad getting sick en route in the Yukon, alone on a remote road without cell service. But my dad’s looming illness only caused him to double down in his determination to forge ahead. As always, his sheer stupid strength of will prevailed. I quietly mapped out hospitals and emergency services along our route, just in case.

Of course, my father was right: he was fine. As we connected the dots on the map – from Calgary to Grande Prairie, White Horse to Dawson City, Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk – I watched in wonder as my middle school geography textbook sprung to life. I traced our route on the map I splayed out on my lap, repeating names of places I had never been before like incantations: Peace River, Quiet Lake, Moose Creek, Mount Monolith, Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in traditional territory.

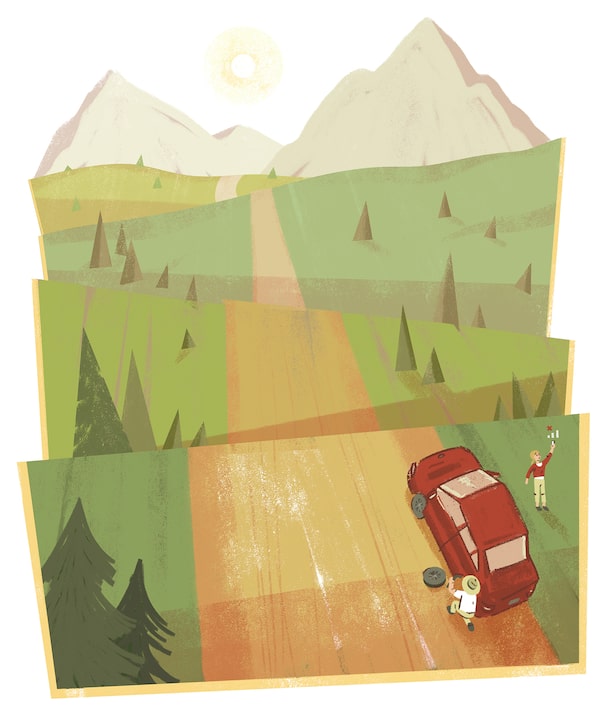

As we approached the threshold of the Arctic Circle, we heard a bang come from under the car. My dad and I looked at each other as we felt the air go out of the tire. Just as I was mentally preparing for our second worst-case scenario – being stranded on an isolated gravel road with no cell service and nary a soul in sight to change a tire with my cancer-patient father – we pulled into a clearing off the highway. We calculated our next move under a sign that read “ARCTIC CIRCLE” beside a placard about the native flora and fauna. I had never changed a tire before. Would Dad be able to do it on his own? I worried.

We popped the trunk and pulled out the spare. I examined it like a foreign object. All of a sudden, as if the winds had turned, the picture of paternal relaxation that had been before me turned to manic determination. Without saying a word, my father’s thin, fragile frame, outfitted in khakis and a Panama hat, lunged forward, grabbed the tools and started in on the tire. I stumbled around, kicking up dirt, unsure of how to be helpful. We took turns trying to loosen the tire, twisting with all our might before it budged. He was single-minded as I wondered what we would do after we exhausted all our options. Could you call a tow truck to the Arctic Circle? We finally manoeuvred the flat tire off the car, and my father’s almost pathological need to persevere carried the day once again.

This October, my father’s cancer transformed into a terminal illness and he was given anywhere from a few months to a year to live. My four siblings and I whispered amongst ourselves: We had been here before, 15 years and one terminal diagnosis ago, and, well, look at how that had turned out. Maybe Dad could beat the odds again – if anyone could, it seemed like he would. I was calling cancer’s bluff.

For more than half my life, I had known him as sick but unstoppable. But when I could finally visit him in the hospital, I didn’t recognize the man in front of me: shrunken, withered, defeated in a hospital gown. Until I saw him I had been resolute, gripped by the naive delusion borne of desperation that if my father chose to fight, then he would win. The man in front of me, who was always eager to the point of obstinate to make it to the very end of the road, seemed to have thrown in the towel. The same force that had propelled him forward in pursuit of more Life with a capital L was the very thing that became the source of so much anguish during his last days.

After my dad died, in the midst of the pandemic and without much else to do, I drove his car around Ottawa, relearning the routes I had never committed to memory as a teenager.

Early in the new year, my brother and I took a road trip to our childhood home in Kingston. What we call the nostalgia tour is a technique that was perfected by our father over many years of dragging us along on road trips to visit old homes, old employers, old friends of his. When we were kids, we always rolled our eyes and pleaded for an actual activity. But on a cold cloudy day in January, Dad was gone and there we were, indulging in the impulse to return to what once was. We paid our respects at the schools we had attended and the house we had grown up in. And as we drove along the highway, the road stretched out in front of us.

Michaela Cavanagh lives in Berlin.