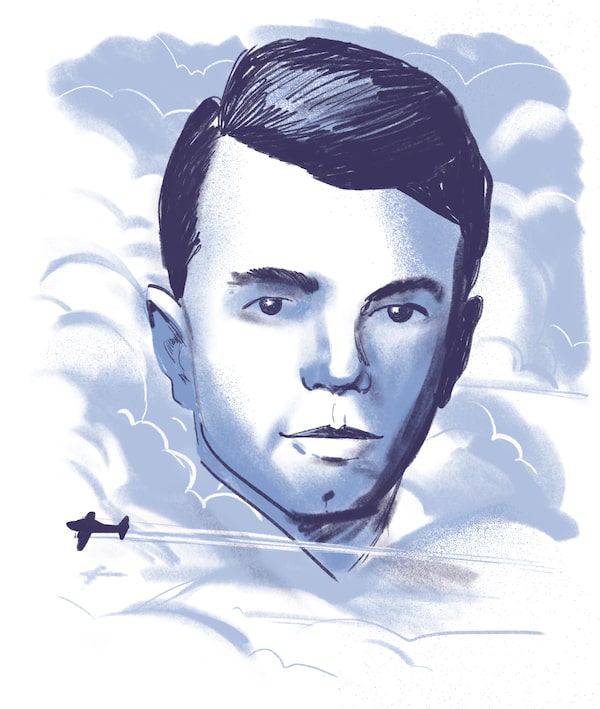

Drew Shannon

First Person is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

This week, First Person reflects on the pride and the heartache of Remembrance Day.

In 1943, Colin Beal was not quite old enough to join the British Army legally, so he lied about his age, and was accepted by the Dorset Regiment. He was sent to fight the Japanese in Burma (now Myanmar). He served under General William Slim in the 14th army, also known as the Forgotten Army. In the spring of 1944, somewhere in the Burmese jungle the Japanese were closing on the British. The battle was sustained and merciless and the Forgotten Army were losing ground. Colin took a grenade to his leg. Gangrene set in. There was not much hope for the young lad from Dorset who would likely die far from home. A Canadian pilot, on an evening mission to drop supplies and evacuate the injured, saw the dying boy on a stretcher in the hospital. He was in a hurry to leave, but persuaded whoever was in charge to tie the boy and the stretcher to the centre strut of his plane quickly because the light was fading and he had to leave.

Colin survived and so did his leg.

When Colin came home from the war, he went to London School of Economics in search of a future. He found it in the bright blue eyes of Jennifer Hall-Patch. My mother says that the first time she saw my father, she was shocked by the size of his ears and pitied the children who were to be his. Seconds later she fell in love, and two years after that first meeting the first of eight big-eared children was born.

In 1951, Colin, Jennifer and the first of their brood left postwar England for a new life in Canada, and settled in Pickering, Ont. Ten years later they had eight mouths to feed, 16 growing feet to shoe, and all the messiness of life with a big family and no money. Like many new Canadians, their fearlessness, hard work, humour and love prevailed over hardship and our family thrived.

As was common among veterans, Dad rarely spoke of his wartime experiences. He just kept calm and carried on. There was never any talk about post-traumatic stress when I grew up but some things now make sense. Dad never wanted to travel in warmer climes, perhaps because of his jungle experiences. When we wanted to wrestle with him, he declined and said, “I can’t, I have a hole in my leg.” In his later years he developed a deep aversion for insects, particularly mosquitoes and black flies. While that could be normal, I remember that he had also suffered terribly from recurrences of malaria, courtesy of the Burmese jungle. I only knew of his war story because I read about it, not because the subject popped up at the dinner table.

In the 1980s, I was visiting my parents sometime before Dad became ill with Alzheimer’s, and, as one does, I was flipping through a pile of papers on the table. My eyes fell on a story from their local newspaper, which featured an interview with my father. My dad had told the reporter about a conversation in the cafeteria at work where some of the men were chatting about their war service. On this particular day he joined the conversation, and shared how he was injured in battle and evacuated by boat to a field hospital that was under attack. He talked about the horror of flying from the field hospital, over enemy fire, and how the aircraft bucked and moaned as the pilot forced it homeward through the dark sky.

According to the article in the Port Perry Star, another fellow in the group was Jack Webb, a retired Canadian pilot. He had flown in Burma during the war. He spoke about a memorable mission – a late arrival at a jungle field hospital, fading light, enemy fire and a soft-spoken young Dorset lad who was dying from a leg injury complicated by gangrene. The Japanese forces were closing from one end of the runway and the British were fighting back as best as they could. Jack told his audience how his conscience wouldn’t allow him to leave the boy where he would most certainly die. He talked about convincing the medics to give the lad a chance and strap the stretcher to the centre strut of the aircraft, above the other wounded soldiers, and to hurry because there wasn’t much light left. He said, “I told the boy to hang on and promised him clean sheets and pretty nurses,” and he told of how they had to fly into enemy fire to leave that wretched place. He talked of how the dark embraced them as they flew back to safe haven, “and I always wondered if that boy made it home,” he finished.

“He did,” said my Dad, tears in his eyes, hand raised.

In the movies, those men would have become staunch friends and attended the various baptisms and weddings of each other’s children. In real life, they shook hands and went their separate ways, and did their separate things, both contributing to their communities and their countries.

I have often wondered if Jack Webb’s family ever knew of his incredible bravery and compassion, and his gift of life to that boy who would have died but for him. Without Jack’s belief that a sick and broken lad from Dorset should have a chance to live, my father would have joined the lost souls of the Forgotten Army in the jungles of Burma.

Without Jack Webb there would have been no story to tell. No big-eared young veteran arriving in Canada. No eight children or 19 grandchildren or 23 (and counting) great-grandchildren. No memories, no joy, no heartache. No legacy.

So, to Jack Webb’s family, and on behalf of mine, I extend our deepest thanks to your brave father. He gave my Dad his life, and by so doing gave all of us ours.

Alison M. Beal lives in Telkwa, B.C.