Architect George Farrow is telling the story about the time a subway car loaded with designers, dignitaries and TTC officials rode along the newly extended Spadina line in 1978, and pulled into one of the stations designed by his firm, Dunlop Farrow Aitken.

“We started at Union Station and we went sailing north to the top end,” the 80-year-old recalls with a twinkle in his eye. “And when we went by Dupont, everybody said ‘Oooohhhh’ because of the colour.”

At Dupont, the peach-coloured, ceramic penny-tile prevails, covering curvy walls and the organic benches that sprout from them; a high ceiling allows artist James Sutherland’s multihued mosaic flowers to grow tall; outside, entry to this groovy TTC stop is via a giant glass soap-bubble beside sculptor Ron Baird’s imposing steel doorway to a transformer site. It’s a heady mix.

The reaction is much the same as the humdrum McMansions along Mr. Farrow’s Oakville street tick past the car window in a blur of beige.

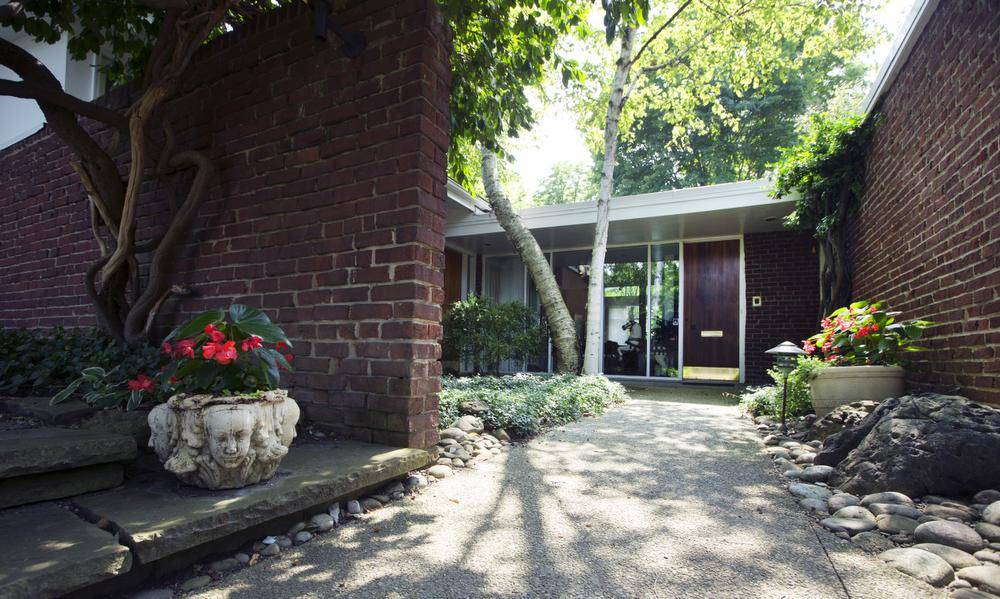

Halfway down the long avenue, a first-time visitor to the Farrow Residence gasps at the sight of the sleek, low-slung Modernist abode.

Designed in 1962 and completed in September 1963, the Breuer-esque home hasn’t changed much since Mr. Farrow completed the last addition in 1973, when a summer porch and pool were added to the back. Before that, in 1970, when the couple’s two young boys were closing in on their teen years and needed more space, the original carport morphed into a bedroom wing, and a garage was tacked onto the other side. Not that you can tell: An architect rarely uses a heavy hand when rejigging his own vision and, in this case, it’s the same “old Dutch” bricks, same window configurations, same massing.

“The point of having an H-shaped design is that you can add on,” observes Mr. Farrow, who is now senior partner, emeritus, at Farrow Partnership Architects and works with son Tye, a senior partner. “It was a nice house but we’ve been able to grow with it.”

Oh, it’s still a nice house despite presenting a somewhat blank façade to the street. Mr. Farrow laughs at the memory of one bold lady who approached one of his boys while out mowing the lawn to suggest that “ ‘Your father mustn’t like people: there are no windows on the front of the house!’ ”

What that poor lady didn’t know is that a great many Modernist homes have a similar configuration; had she ventured further to see the delicately composed, semi-enclosed courtyard containing the front door and a wall of welcoming windows, or snuck around back to see the mostly-glass façade, she would’ve changed her tune.

From that courtyard, one enters the home through a full-height door into the crossbar of the H; from here, one can choose to go left past the dining room filled with Georg Jensen furniture, past the small kitchen, and into the boys’ 1970 bedroom wing. Or, a right turn will lead to the original bedroom wing that now contains only the master bedroom and one small child’s bedroom, since the bedroom that shared a wall with the master was sacrificed for a walk-in closet and larger master bath.

Of course, most folks will be drawn to the massive fireplace in the formal living room that’s straight ahead and down a few steps. Here, under a gently peaked ceiling, one drinks in nature via a window-wall that welcomes the backyard greenery inside, or contemplates Ron Baird’s metal crow skeleton hanging beside the fireplace. And if dead crows aren’t one’s bag, there’s a lovely portrait of Mrs. Farrow’s great, great aunt Maria Duncan.

Either way, it’s a great room for art, since on the other side of that peaked ceiling there’s a clerestory to admit even more light: “If you come in the morning, the sun comes through from above; even in the kid’s area we have clerestories,” Mr. Farrow beams. “There are no dark corners, even the closets.”

Adds Tye: “As a kid you’d lie on the floor … on the carpet, with the sun shining in, and look up at the trees.”

About those closets: A stickler for straight lines, Mr. Farrow cantilevered the inside of the boys’ closets into the yard so that their rooms would remain square; it’s a neat architectural trick that allows the closet doors to sit flush with the windows. Other neat tricks, such as peek-a-boos into other rooms, or changes in ceiling heights, offer interest and surprise.

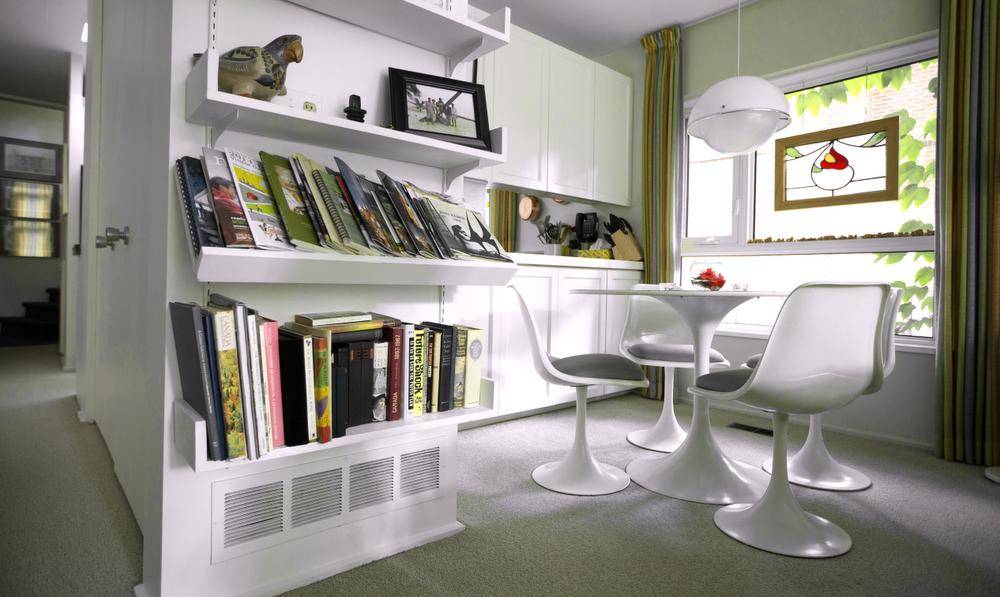

While inherited antiques and wallpaper have crept into some areas of the home over the decades – Tye recalls growing up with angular Danish teak and white walls punctuated by small bursts of colour – some original furniture remains in the cozy family room and elsewhere.

Peppered throughout the 3,000-square-foot home are Mr. Farrow’s intricate and amazing carved birds, a hobby that has kept the 1958 University of Toronto graduate “out of trouble” and “away from the television” (and perhaps out of wife Diane’s hair?) – when he wasn’t designing hundreds of hospitals, schools and churches.

While the one-storey home has served them well (Mr. Farrow jokes that when his wife Diane and he get old, they can “wheel around” the place), it’s altogether possible that Dupont station will outlive it, unless the current appetite for ‘Midcentury Modern’ design elevates to GTA housing stock as well.

“Two doors up, a brand new house, and there are two more coming,” Mrs. Farrow observes with a sigh. “That’s what’ll happen … they’ll bulldoze it.”