Under the clear blue sky his country had manufactured for the occasion (by closing factories for miles), Xi Jinping stood stony-faced on an enormous red carpet to receive a clutch of world leaders. One by one, statesmen from near and far walked up to the Chinese President to shake hands on the occasion of his first military parade last September. Standing next to his wife, Peng Liyuan, Mr. Xi barely spoke, his face opening into only the thinnest of smiles.

It was hardly the warm greeting of a host. His bearing recalled something else entirely. In the Forbidden City, the centre of Chinese imperial power since the 15th century, Mr. Xi wore a double-pocketed Mao jacket but had the air of an emperor, coolly accepting foreign tributaries.

One of the first to arrive was Dmitry Mezentsev, a Russian politician and secretary-general of the Shanghai Co-operation Organization, the China-led Eurasian military and intelligence-sharing bloc designed to challenge U.S. dominance in the region. Mr. Mezentsev placed his right hand on his heart and bowed before Mr. Xi. Moments later, a formidable display of Chinese tanks and long-range missiles rolled down the Avenue of Heavenly Peace.

Xinhua, the state-run news agency, tried to capture the spirit of the moment: "China will not be bullied again, and the dream of national rejuvenation is coming true." For decades, China scrupulously followed the maxim of former leader Deng Xiaoping to "hide your strength, bide your time." Even as they orchestrated an economic revolution at home, its leaders trod softly on the world stage.

But things have changed. Under Mr. Xi in recent years, China has struck an increasingly assertive posture, demanding that the world bend to its interests in diplomacy, corporate affairs and the drawing of international borders. When they gather here for G20 meetings next week, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and other foreign leaders will encounter a Chinese leadership newly eager to shape the outside world to its own needs.

In the past few years, it has installed mountains of sand and, later, military jets on rocks it claims in disputed seas. It has launched ambitious attempts to redraw Silk Road trading routes and link continental electricity systems, ideas that both serve China's fundamental interests. It has reached into other countries to silence critics and squeezed foreign corporations operating inside its borders. It has warmed to nations willing to co-operate with its trading agenda, and then angrily rebuked them when it is rebuffed.

Diplomats stationed here say there is one way to make sense of it all: The empire is back.

For the better part of 2,000 years, China was ruled by imperial dynasties, their names now shorthand for the country's national narrative. Emperors saw themselves in command of tianxia – "all under heaven." They ruled with unquestioned authority at home and exacted tribute from the lesser nations outside their borders, who sent emissaries from as far as eastern Africa to kowtow to the emperor – a ritual of obeisance that involved kneeling three times, and prostrating nine times.

For most tributaries, the relationship was fruitful. They acknowledged the superiority of the emperor. China, in turn, showered them with gifts and trading privileges often worth many times what they had brought the imperial court, and the emperor then typically left their nations alone. That made the empire very different from the conquering and colonizing of subsequent European expansion.

Imperial China saw itself as the centre of the civilized world, a step above the barbarians on its flanks who could not match its technological, cultural or military prowess, and it demanded others acknowledge the same. Scholars call it a form of "ethnocentric hegemony."

Then it all crumbled, the victim of Western incursions and a sclerotic governance system that could not keep pace with modernization. The last empire, the Qing, frayed in the 19th century, giving way to years of warring and domination by foreign powers. With the demise of empire, the Middle Kingdom became a guojia, a country like any other.

Into that humiliation stepped the Communist Party, which under chairman Mao Zedong consolidated authority but created its own decades of devastating turbulence. What emerged from Mao was a political system that, while ruled by a single party, governed by elite consensus.

Mr. Xi is different. He has assembled a collection of titles that give him personal leverage over many instruments of internal power. He has moved faster than his predecessors to vanquish rivals and stamp his own ideology onto China's commercial development. He has, to a degree not seen in decades, squelched dissent and waged war on Western values. He has, too, ordered artists to avoid "vulgar" works and banned "weird architecture" – the kind of edicts that make more sense as whims of a modern regent than diktats of the party. China's emperors, after all, were expected to have "the final word in every aspect of life," China historian John King Fairbank once wrote. "China used to be a great power during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Now it is on its way back," says Bo Zhiyue, an expert on China's elite politics at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand.

Past and present: Souvenir plates for sale new Tiananmen Square in Beijing honour Chairman Mao and President Xi, left, who has assembled more personal leverage over state power than was allowed in Mao’s consensus-rule system.

Andy Wong/AP

As its leaders seek renewed recognition of China as a great power, "they are looking at the shadows of themselves, of the past," he says. "They have no other role model to look at."

Witness the modern-day demands for obeisance. China uses its economic clout against countries that speak out against its treatment of religious groups or support its dissidents. Steer clear of those sensitivities, and China offers rewards of investment, market access and other signs of financial goodwill. Meet the Dalai Lama – and risk being frozen out.

"They want you to kowtow," says Timothy Cheek, co-director of the Centre for Chinese Research at the University of British Columbia . "The tone is very different now."

Such a mentality is at odds with China's current situation. Its economy has grown unsteady, while its neighbours have increased their reliance on Washington, rather than Beijing. Although it is has begun to show technological leadership in some areas, China remains well shy of global military and cultural dominance. If it's an empire today, it's one with few vassal states – and mounting problems at home.

Still, the country's extraordinary rise in economic power, and the speed with which it is closing the gap with the U.S., has underpinned a view inside China that history gave it a rightful place in the world, one it will soon retake. "There is this sense that China was the senior state in East Asia, that that was appropriate, and that it prevailed from the Tang Dynasty [7th to 9th century] forward – and would not be inappropriate in the 21st century," says Timothy Brook, a historian of China's imperial history at UBC.

Inherent in that view is a rethinking of state equality, which underpins the modern world order. What has grown popular in some Chinese quarters, instead, is a strain of thought that harkens "back to the tribute system. I think that legacy is still there," Prof. Brook says.

As state councillor Yang Jiechi, the country's most powerful foreign-affairs figure, once told a Singaporean official: "China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that's just a fact." The same tone clattered into Canada earlier this year when Foreign Minister Wang Yi sternly told a reporter she had "no right" to question the way his country manages its people.

The shift in attitude began nearly a decade ago, when the success of the Beijing Olympics brought a swell of confidence and national pride, while the financial crisis offered validation that China's system was superior to the Western notion of the free market.

There is "a sense that China doesn't have to go cap-in-hand any more," says Prof. Cheek.

"But is that a return to Chinese empire thinking? Or is it like Japan and Germany, years ago, saying: 'Look, we've played by the rules, we've developed. We want respect and we're not getting it.' There's always these tensions with rising powers."

No country, of course, is monolithic, particularly one as large and diverse as China, which has long pledged that its primary goals are a "win-win" desire to build up others as it builds itself.

Even so, "it has been China's dream for a century to become the world's leading nation," according to Liu Mingfu, a Chinese military commentator and former colonel in the People's Liberation Army. His 2010 book, The China Dream, was initially pulled from shelves for fear of angering the U.S. But it was re-released three years later, shortly after Mr. Xi made "China Dream" his mantra – he has repeated the term time and again. "The Chinese people are seeking to realize the great renewal of the Chinese nation," he said last year.

That means Beijing "guiding the world through exercising leadership and management," Mr. Liu writes. In explaining the country China wants to be, he describes the place it once was – an empire surrounded by vassal states who paid it tribute.

"China's emperors treated the kings of smaller nations like little brothers," he writes. "Strong and not abusive to the weak, large but leaving room for the small; governing ethically, treating all benevolently … the values that define China's personality."

He adds: "Kingliness is China's national character. When China becomes the most powerful nation in the world, this character must not change."

It's a notion with parallels to Vladimir Putin's bid to return his country to the days when it was feared. "Russia has been a great power for centuries, and remains so," he said in 1999 upon being elevated to prime minister under president Boris Yeltsin. It's a vision of what one Russian historian called "great power chauvinist imperialism" with roots in a 16th-century belief in Moscow as a "third Rome."

Promises to restore past glory hold great allure across cultures: Like the Donald Trump campaign to "make America great again," such slogans often serve domestic political aims.

China, too, clings to the notion that ancient history remains modern destiny. "There's a real feeling among elite Chinese that China's time has come," says Geoff Raby, a former Australian ambassador to Beijing.

But, he says, "I don't think it's the empire coming back, because the empire was very inward-looking. With Xi, there's a more creative and innovative foreign policy than we've seen from China for a long time."

President Xi arrives in Washington for Nuclear Security Summit meetings last spring: The U.S. remains a dominant power in Asia and has retained strong ties with China’s neighbours, such as South Korea, despite the courting attempts of Beijing.

JONATHAN ERNST/REUTERS

Mr. Xi has mobilized a sweeping set of ambitions to make Beijing a central seat of influence. By creating the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, China has challenged the supremacy of financial institutions led by the U.S. and Japan – a disruption to the existing order underscored by Britain's eagerness to join the AIIB over Washington's objections (Canada also is expected to apply soon for membership.)

China's military is expanding its reach, with an increasingly capable – and mobile – navy and construction of its first overseas military base, in Djibouti, near the entrance to the Red Sea and waters that carry nearly half the country's oil imports.

Chinese companies, meanwhile, are expected to buy $1-trillion (U.S.) in foreign assets in the next five years even as China's leaders press their own advantage at home by pressuring foreign companies and expanding the reach of state-owned firms.

Take State Grid Corp., which has snapped up electricity assets on four continents and is now championing a concept to connect the entire world with a common network of transmission lines. Global Energy Interconnection, as State Grid calls it, would sift together electrons from Arctic wind turbines and Sahara solar panels – at a cost of $50-trillion (U.S.).

Mr. Xi himself has spoken in favour of the idea, just as he has been the leading proponent of the new Silk Road, also known as One Belt One Road – a plan to integrate Central Asia and Europe into new trading routes and relationships with China.

In ancient times, the Silk Road provided an avenue for dynastic expansion, from the Han in its early days, to the Mongolian Empire more than a millennium later. In seeking to revive it, the scale of China's ambition is stunning: Over 30 to 40 years, it could involve up to 65 countries representing 40 per cent of the global GDP, according to an analysis completed by London-based Eurizon SLJ Capital. Those countries could see new development and improved living standards, while China sees a chance to speed international acceptance of the yuan, extend the reach of its companies, and expand its regional influence.

It's already happening, with $250-billion (U.S.) in projects under way in 50 countries, a mix of road construction, railway building and electrical upgrades. Last year, a train for the first time carried containers from southern China to Rotterdam.

Stephen Jen, co-founder of Eurizon, calls it a Chinese echo of the U.S.-led Marshall Plan for the postwar reconstruction of Europe, with a key difference. Spending on One Belt One Road could reach $1.4-trillion (U.S.), which, adjusted for inflation, is 12 times the Marshall Plan investments. "China is now wealthy enough to be able to do what the United States has done," he says. "It will be in the long-term interests of China – for stability or more leverage."

If the Silk Road encapsulates the Chinese desire for a new pre-eminence, however, it resembles not so much the re-establishment of old dynasties as a mimicking of a very modern power structure.

"They're pursuing a very aggressive foreign policy that is probably closer to the American empire than the Qing dynasty," Prof. Brook says.

There are parallels. Khong Yuen Foong, a scholar at the National University of Singapore, has argued that the U.S. has itself echoed imperial China by devising "the most successful tributary system the world has ever seen." Washington's market clout, sway over international organizations, and military supremacy buttress its place as the world's central power.

The steps China is taking suggest a desire to replicate, if not replace, that U.S. role.

"Their long-term aspirations must be to replace the U.S. as a hegemony in Asia," Prof. Khong says. "You just want to be the top dog if you can do it, because it brings a lot of psychological and material benefits."

Important Chinese voices have urged an even more assertive pursuit of that goal. China should pursue formal military alliances, build more foreign bases, and openly compete with the U.S., according to a formulation promoted by Yan Xuetong, dean of the Institute of Modern International Relations at the prestigious Tsinghua University. State media call him one of the country's top thinkers.

Look to the U.S., though, and it also becomes obvious how such efforts might stumble. The U.S. has fashioned itself into the city on a hill, with a lifestyle and political system that are both desirable. China's coercive model offers less appeal. The U.S. has Hollywood and Google. China has a heavily censored Internet and a jailed Nobel laureate (human rights activist Liu Xiaobo). And while China also boasts some of the world's most innovative minds and finest artists, its "soft power, or ideological power, is not that attractive," says Prof. Khong.

Mr. Yan has a solution for that, too, saying China needs to return to its ancient roots, and a philosophy of "humane authority," a shift that would allow, for example, free speech. One of his books is titled Ancient Chinese Thought, Modern Chinese Power.

For now, though, China's strategy appears to be winning it fewer friends, rather than more.

"Rather than the empire being back, what you are seeing is an arrogance and boorishness in China," says Jorge Guajardo, Mexico's former ambassador to China. "It's sort of like the boorishness you see in the new rich. And most likely, it will backfire, big time."

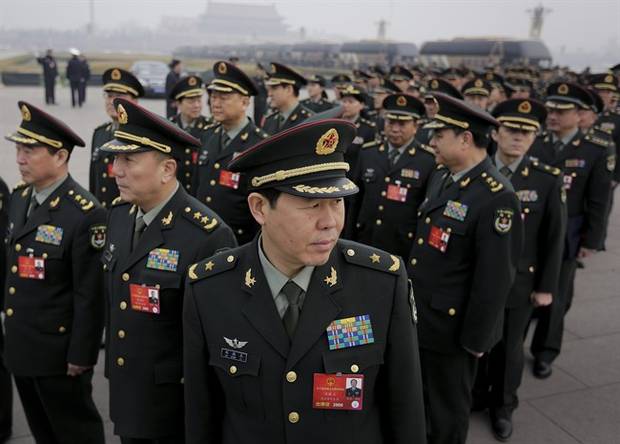

Delegates from China’s People’s Liberation Army arrive at the Great Hall of the People to attend a session of National People’s Congress in Beijing on March 4, 2016.

Andy Wong/AP

China's aggressive expansion in disputed maritime areas has angered many of its neighbours. Recent years have brought many other diplomatic failures. Beijing has courted South Korea, which has turned instead to the U.S. and its missile-defence technology for additional protection against North Korea's rising nuclear threat.

Promises of a "golden era" with the U.K. have also receded since the British government delayed approval of a Chinese-backed nuclear plant, with observers citing national security concerns. It's a direct rebuff to Mr. Xi, who signed the original deal and saw it as key to expanding China's corporate ambitions.

In Hong Kong, meanwhile, China's creeping erosion of local freedoms, and accusations that it abducted local booksellers to silence them, has given rise to a growing independence movement.

Yet even if China's assertiveness has not won it friends, it's something other nations must confront, Mr. Guajardo says.

"How long will it take the rest of the world to learn this?" he wonders. "You see all these countries trying to engage in the old Chinese way, expecting China will always seek to please. When in fact, now you're bumping into a China that has no interest in pleasing. It only wants its way."

The question of how to approach China has vexed foreign powers from the moment European and Ottoman emissaries first landed on Chinese shores in the 16th century, only to have the emperor demand his tribute.

Mr. Guajardo sees a simple, if difficult, approach: Say no, and do it together.

That moment may already be arriving. This summer, an international court of arbitration ruled against China's historical claim to waters in the South China Sea. China's foreign ministry sneered, saying the decision was "invalid and has no binding force."

Other nations countered quickly. The U.S., Japan and Australia issued a rare joint statement calling all sides to respect the ruling – an obvious prod at China. Canadian Foreign Minister Stéphane Dion, too, said: "Canada believes that the parties should comply with it."

That, Mr. Guajardo said, "is how they start saying: 'Enough.' "

Beijing's "threats are no longer as valid when the world acts more and more in unison."

Nathan VanderKlippe is The Globe and Mail's correspondent in Beijing.