July 1, 1939: A crowd gathers for a ceremony at the opening of the Canadian Pavilion at the New York World's Fair, whose slogan was 'The World of Tomorrow.'Handout

Gerry Flahive is a writer and consultant based in Toronto.

July 1, 1939, may have been Dominion Day in Canada, but it was Canada Day at the New York World’s Fair. Dignitaries, Mounties, sailors and “several thousand Canadians and Americans of Canadian descent” gathered outside the national pavilion, a stolid, low-slung building located in one of the less-prominent quarters of the spectacular fair. The RCMP band played The Star-Spangled Banner, God Save the King and, of course, our beloved de facto national anthem, Old Canada.

Well, that’s how The New York Times reported it. But even if it is more likely that the band was actually playing O Canada, “old” wasn’t far off as a descriptor for what lay inside the pavilion. Its design (an architecture critic later described it as an “uncomplicated massing … passed unnoticed by all but the most diligent visitor”) and dreary contents (e.g., complex charts showing the industrial uses of such chemicals as crotonaldehyde, and a statue of a loincloth-clad man representing the mythic figure of “Water Power”) revealed a country that, though about to be galvanized into a defining role in the Second World War, couldn’t rouse itself to a slightly ebullient boast. The pavilion also somehow neglected to include any substantial evidence of the existence of Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia and Prince Edward Island.

The 1939 pavilion's futuristic buildings loom behind an RCMP equestrian parade on Dominion Day, the holiday now called Canada Day.Handout

Upon its opening in the spring of 1939, planner and architect Humphrey Carver didn’t hold back. Writing in the Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, he declared, “Let us discard mere politeness and frankly confess that for Canadians the World’s Fair is a scene of humiliation. The display which the Minister of Trade and Commerce has placed inside the Canadian Pavilion is the most ineffective piece of work in the whole Fair. This is the unpleasant truth that has to be faced. Canada alone makes no reference whatsoever to the lives of its citizens.”

Journalists, art critics and cultural historians chimed in at the time, and in the years since, about the structure and its contents: “A bitter disappointment.” “Instantly forgettable.” “Rather dull, if not stupid.”

Over the course of two editions of the fair, in 1939 and 1940, six million people saw this image of Canada, as the pavilion benefited from the attendance of 44 million people who came to experience what the fair’s president, indefatigable promotion man Grover Whalen, described as “the best of our modern civilization.” This included new wonders such as televisions and fax machines, masterpieces from the Louvre and the Uffizi Gallery, Elektro the Robot, a 70-foot-high cash register, designs and art by Alexander Calder and Salvador Dali, and General Motors’ massive interactive exhibit Futurama, depicting the superhighway-embroidered cities of the far-off world of 1960. The button given out by GM came to encapsulate the fair for many: “I Have Seen The Future.” Canada might as well as have issued buttons reading: “Nothing in Canada Happens Indoors.”

Some of the 1939 expo's futuristic attractions included Elektro, a robot that could count on its fingers and smoke cigarettes, and the Perisphere, a hollow ball 58.5 metres across that housed the fair's 'theme centre.'Associated Press; Fox Photos/Getty Images

World’s fairs – gaudy, encyclopedic, political, provincial, architecturally extreme, simultaneously nationalistic and anti-nationalistic – have always sought to encapsulate the world through what we now think of as experiential entertainment and storytelling. National pride is at stake. As Evan Potter put it in his 2009 book, Branding Canada: Projecting Canada’s Soft Power Through Public Diplomacy, “if a country fails to tell its own story, its image will be shaped exclusively by the perceptions of others.” It didn’t seem to occur to Canada in 1939 that it had much of a story to tell.

Canada is now preparing to present its story to the world at the Dubai Expo 2020 (which will run from October, 2020, to April, 2021) and will spend $40-million to do so. It’ll be Canada’s first appearance at a world exposition since 2010 in Shanghai (the Harper government having decided to skip fairs in Korea, Italy and Kazakhstan). It will come in the context of a recent Senate report, Cultural Diplomacy at the Front Stage of Canada’s Foreign Policy, that noted that (according to research by the Anholt-GfK Nation Brands Index) “a lot of people don’t know anything at all about Canada.”

Global Affairs Canada, in a document soliciting ideas for Dubai Expo 2020, has indicated that the “Canada Pavilion will be the physical, visual and experiential representation of Canada … presenting an image of Canada as a global leader, innovator and ally with solutions to offer the world in many spheres: free trade, human rights, gender equality, international security, migration, and diversity, sustainable development, food and water security.” Under the theme “The Future in Mind,” the government will aim to “highlight Canadian leadership in key sectors including advanced technologies, artificial intelligence, digital innovations, aerospace, clean energy and education.”

Will all of that add up to what we should, or could, be saying about Canada? What happens when you distill a country into a world’s fair pavilion?

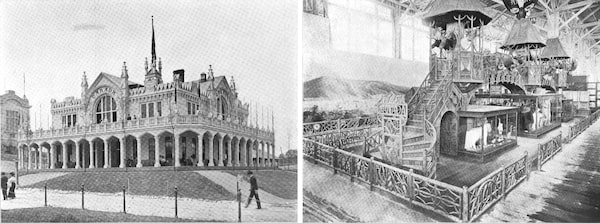

At the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, the Canadian pavilion was a Gothic structure designed by Lawrence Fennings Taylor. Inside were murals and paintings of Canadian life, as well as a 'Palace of Forestry, Fish and Game,' shown at right, with thousands of specimens of Canadian wood.The Greatest of Expositions Completely Illustrated (1904)

Canada's pavilion at the 1962 world's fair in Seattle highlighted Canada's scientific achievements, and envisioned a model city showing what Arctic life could be like by the 21st century. Dubbed Katyaarna, ('the pleasant place' in Inuktitut), it included apartment blocks in a concrete dome and a submarine port.Seattle Public Library; Morley Studio / University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections

In preparing for the 1939 fair, bureaucrats at the Ministry of Trade and Commerce in Ottawa weren’t thinking quite so broadly. Even so, their efforts weren’t much influenced by scathing reviews of Canada’s participation at previous expositions, such as the one in Paris in 1937 and Glasgow the following year.

Perched underneath the Eiffel Tower, Canada’s Paris building was a stylized grain elevator, attached to the side of the British pavilion. Two previous designs, including one with “reliefs of beavers alternatively head up and head down” were rejected by the fair’s chief architect. At the Empire Exhibition in Glasgow in 1938, the British magazine Architecture decreed that the Canadian pavilion’s exhibits, which included “a row of highly-coloured paintings in flashy gilt frames, together with a few stuffed animals placed on a shelf below,” were “probably the most inept piece of display in the whole Exhibition.”

Despite such admonitions, the government seemed not to grasp the colossal scale and rocket-powered boosterism of the New York fair and its megalomaniacal corporatism, which almost seemed as though it could single-handedly pull the United States out of the Great Depression.

The 1939 World's Fair grounds, shown at night.Everett Collection / The Canadian Press

Is it fair to project our 21st-century perceptions and expectations of Canada onto what was then a very different country? Smaller and poorer countries such as Finland (its Alvar Aalto-designed building was considered an architectural masterpiece) and Ireland (which transformed its national symbol, the shamrock, into a modernist glass wonder) transcended expectations in New York in 1939.

By the early 1930s, Canada’s population had already become more urban than rural, but the mental and cultural shifts that implied were lagging. New Yorker satirist and artist Bruce McCall captured some of the vibe of the time, as a child growing up in the million-watt cultural glare of the United States in the late 1930s, in his memoir Thin Ice: Coming of Age in Canada: “The Americans had Franklin Delano Roosevelt at the helm. We had a dyspeptic-looking old bachelor, Mackenzie King. Everything exciting, bold, and glamourous in life could be traced back to America. Canada declined to soar in any way. Nobody seemed to have big dreams. Nobody wanted to stand out. Save for annual wheat-bushel quotas and snowfall records, excess might as well be legally outlawed.”

Mr. McCall wasn’t far off. The official program book of the fair described what awaited visitors to the Canadian pavilion: “A huge illuminated map painted on burnished copper, shows aviation routes, mounted police outposts, grainfields and mining areas.”

A competition drawing of W.F. Williams's winning design for the 1939 Canadian pavilion.

Could the building itself have exuded a better sense of Canada? Architectural historian Elspeth Cowell notes that a movement was emerging in the 1930s among some domestic architects to develop a distinctive Canadian style. W.C. Somerville, president of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, urged the government to hold a competition “in order that this building be truly representative of Canada, Canadian materials and Canadian architecture.” But the actual competition brief, as Ms. Cowell writes, “made no reference to the Canadianism of the building,” it perhaps being thought that “the building stylistically would inevitably be Canadian.”

Ms. Cowell remarked in an interview that “at the 1939 World’s Fair the American contributions were influenced by Streamline Moderne, a design movement that extended from architecture into cars and product design. It didn’t really exist in Canada in the same integrated way. Architecture was still pretty backwards in Canada at that point, kind of bumbling into modernism.”

Modern or moderne would not accurately describe the heftiest handout at the pavilion, the grimly titled Canada 1939: The Official Handbook of Present Conditions and Recent Progress. Its 176 pages were so stuffed with industrial numbers that they would exhaust even the most fanatically dedicated statistician, its audience limited by its own dour ambitions (”this handbook … has not been compiled for indiscriminate distribution”). Human beings pop up only occasionally in its pages, as its primary interest was in things that might appeal to foreign investors, with photographs such as “Drums of Canadian Refractory Cement being Unloaded at Calcutta, British India” or “Weighing Canadian Oats on Discharge from Steamer at Bristol, England.”

A Department of Mines and Resources employee on site at the fair wrote back to Ottawa to report that “our expenditure was insignificant by comparison with many of the foreign buildings. The Canadian building was not fantastic or ultramodern in any way. It had no marble floors or marble stairways, no rich hangings and costly works of art.” (Perhaps he was forgetting the Group of Seven paintings and other Canadian artwork that had been shunted into a building next door.)

And while other countries sold souvenirs, served their traditional cuisine or had orchestras that “rendered national airs,” he seemed relieved that “Canada had none of these things, and it may perhaps be argued that their absence conferred a desirable sense of dignity.” The only thing missing, he suggested, was any information about the Dionne Quintuplets.

It’s astonishing to consider that only 22 years after the New York fair closed in late 1940, Canada was awarded the right to play host to what is now generally seen as the most successful world’s fair of the 20th century. As a national project, the Centennial celebrations were richly funded, but also gave a context for Montreal’s Expo 67 that demanded a scale and breadth of ambition that most fairs would never have. Canada scored high again with Expo 86 in Vancouver and continued to shine abroad at fairs in Seville and Aichi. At Shanghai, it commissioned Cirque du Soleil to program the entire pavilion, which was built by SNC-Lavalin.

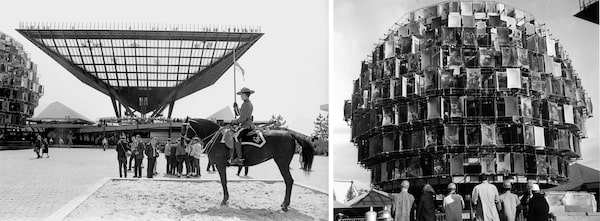

Expo 67 in Montreal was a showcase of Canadian nationalism for the 100th anniversary of Confederation. Visitors could see Roderick Robbie's 'Katimavik,' an inverted pyramid, and The People Tree, whose flag-sized nylon 'leaves' depicted scenes of Canadian life.John McNeill/The Globe and Mail, The Canadian Press

Expo 86 in Vancouver brought the city a distinctive geodesic dome building, now the Telus World of Science. At right, children gather on opening day around Expo Ernie, a talking robot.Hans Deryk and Tibor Kolley/The Globe and Mail

The deadline to bid to build Canada’s pavilion at Dubai has only recently passed, but several dozen other countries have already announced their designs and preliminary programming plans. However, distinctive national brands aren’t exactly obvious from their PR blurbs:

- United States: “Personal rocket ships, robot surgeons and more, in a pavilion that looks like it’s moving”

- Japan: “A high-tech experience based around the themes of water, wind and light”

- Germany: “An engaging look at an environmental trailblazer and a grand finale featuring swinging seats”

- Austria: “See the benefits of low-tech innovation and enjoy a cultured chat over coffee”

- Britain: “A continuously changing poem on the exterior, generated by artificial intelligence and visitors’ contributions”

- China: “A symbol of hope and a bright future”

What future might we have in mind? Getting unstuck from some of our past mindsets might help.

Irvin Studin, editor-in-chief and publisher of Global Brief magazine and president of the Institute for 21st Century Questions, recognizes something that still lurks in the Canadian psyche, something of the “old Canada” that rears up when we step onto the world stage. It goes back as far at least as Sir John A. Macdonald’s picture of Canada as “a subordinate but still a powerful people.” Mr. Studin calls it “aw shucks nationalism,” a country that tells itself, “I’m much smaller, but I’m awesome right?”

Dubai, 2018: An event at the Burj Khalifa marks two years to go until the 2020 expo.Christopher Pike/Getty Images

How might we stand out at Expo 2020? Mr. Studin puts forward the idea that Canada could seize the moment and do something radical, such as presenting the Canadian Arctic as a potential northern Dubai or Singapore, picturing Canada as the Arctic crossroads. It would be about altering our mental image of distance and influence, perhaps something a world’s fair could help kick-start.

Since Expo 2020 is forecasting that 80 per cent of its attendees will be from the leisure market, it’s probably a safe bet they won’t be looking for lumber and crotonaldehyde in the Canadian pavilion. Roughly 21 per cent of the business visitors will be from China, so in the current political climate, how might that influence Canada’s messaging?

At the Venice Biennale, each country is represented by just one artist. What if we did something like that at Expo 2020, giving the pavilion over to, say, choreographer and dancer Crystal Pite or the people of Gander or Tanya Tagaq or 10 Syrian refugees who have settled in Canada or immersive entertainment artists Félix Lajeunesse and Paul Raphaël or comedian Samantha Bee or artist Kent Monkman or writer Michael Redhill or singer Charlotte Cardin … or Bruce McCall?

Amanda Coles, a professor of arts and cultural management at Deakin University in Melbourne (and an expatriate Canadian), remarks that “this is an important opportunity for Canada to leverage the global social capital it currently enjoys as a comparatively progressive nation state, committed to human rights, immigration, social policy and multiculturalism. To argue that Canada’s social capital on the international stage is to be maximized at a World’s Fair is not to gloss over the foundational challenges of Canadian society. But we must be much more than what we are not.“

The ghost of Humphrey Carver might help. He urged Canada to look beyond the failings of 1939’s pavilion: “Even in our most cynical moments Canada is, for most of us, a country of thrilling though elusive potentialities. The future of the country depends upon our success in conveying some of this thrill both to our own countrymen and to those others upon whose co-operation we must depend. That is presumably the purpose of Canadian participation in a Fair. It is an opportunity to project our national ideals and ambitions into three-dimensional form, that they may be seen and understood. It is not that we lack skilled designers. We have plenty of ideas. The World of Tomorrow is upon us already.”

Perhaps Mr. Carver’s pleas will influence Global Affairs Canada’s planning for Expo 2020. But the Canadian government clearly wasn’t listening to him when it slightly rejigged its pavilion for the 1940 edition of the New York World’s Fair. Or to the Financial Post, which pleaded, given our critical role in the war recently under way in Europe, for a presence at the Fair “more worthy of Canada,” one that “would show Canada in her true light as an increasingly potent influence in world and Empire affairs.”

There were more practical matters at hand. The pavilion itself was sinking slightly, as parts of the fair had been built on the foul “valley of ashes” garbage dump described in The Great Gatsby. The stuffed moose on exhibit was considered “a poor specimen,” so it was replaced. And a small “Canadian Cinema” was added next door to showcase, along with tourism films, a 3-D short about the Dionne Quintuplets.

Oh, Canada.