Adolph Friedländer, Comedians de Mephisto Co. Allied with Le Roy-Talma-Bosco, 1905.All images © McCord Museum / the Courtesy of Art Gallery of Ontario / Purchase, funds graciously donated by La Fondation Emmanuelle Gattuso/Handout

David Ben is the artistic director of Magicana and a guest curator of Illusions: The Art of Magic, which opens at the Art Gallery of Ontario on Feb. 22.

“What’s old is new, and what’s new is old” is an appropriate aphorism for magic – that is, for conjuring.

It was true for the first golden age of magic – roughly 1880-1930, as depicted in the chromolithographs on display at the Art Gallery of Ontario, drawn from the Allan Slaight Collection at the McCord Museum in Montreal. And it remains true for what can be described as the current golden age, ushered in by Canadian magician Doug Henning through his television specials in the early 1970s.

As every culture, every society, every country seems to have its own form of magic, magic was and is a global phenomenon. So much so that Charles Carter, for example, carted 31 tonnes of equipment over the course of seven world tours between 1907 and 1936. And the tricks – the effects – magicians perform today are essentially the same because, like notes on a musical scale, there are only eight basic effects. The first four are the ability to make things disappear and reappear; to transform a person or object into something else; to make a person or object pass through or penetrate something; and to suspend the law of gravity. The remaining four effects are based on purported psychic phenomena: divination, clairvoyance, telepathy and telekinesis.

Interestingly, these effects can be used for good or evil. Teleporting a playing card to an unexpected location can generate much mirth – but it can also determine who receives a winning hand in a game of Texas Hold’em. One can divine another’s innermost thoughts on stage in a grand feat of entertainment, or use that same skill to “advise” (more correctly, direct) a bereaved soul in deeply personal areas of love, life and financial affairs. The desire for spiritual advisers was particularly rampant in times of global conflict, such as the First World War. This same need for counsel is just as prevalent today as people seek answers to what magicians remind us in these posters are “the most enduring questions of all time.”

Today the internet facilitates fraud and deceit; back then, magicians had to work at it. Unscrupulous operators would draw on information assembled and traded among spirit mediums, the same way a scouting report is used to size up promising athletes, as the fraudsters moved from town to town. A popular ruse was posing as a door-to-door Bible salesperson. More often than not, the fraudster would be given access to the family Bible. A quick peek would reveal branches of a family tree with more than enough personal information for a spirit medium to establish their credentials. Today, it’s just a few clicks away using ancestry.com.

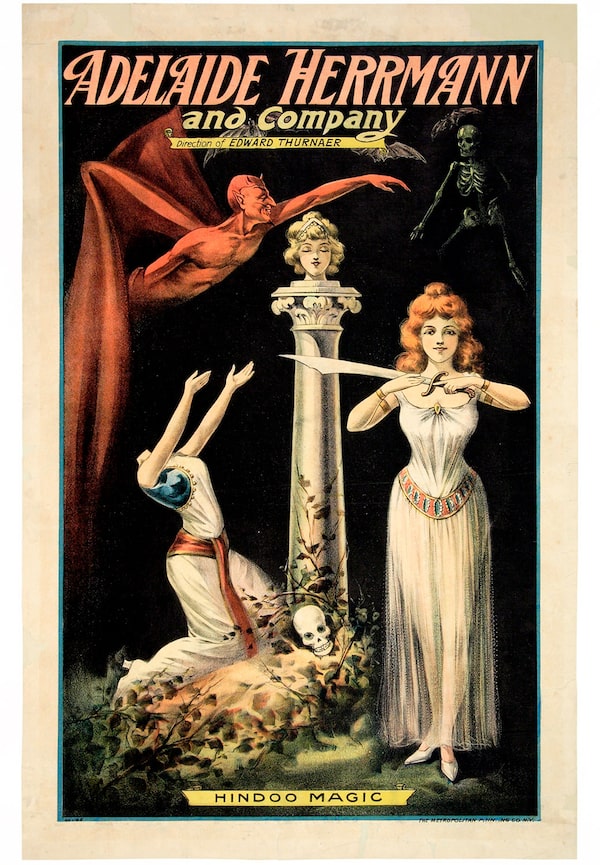

The Metropolitan Printing Company, Adelaide Herrmann and Company, about 1905.

Magicians were masters of cultural appropriation. There are many examples in the exhibition, particularly of Western magicians portraying themselves as Asian – both onstage and off – capitalizing on the then-burgeoning interest in all things exotic. My favourite: Fu Manchu, the onstage persona of David Bamberg, an eighth-generation Dutch-Jewish magician who was raised in the United States and educated in England and found fame in South America performing as a Chinese magician who spoke Spanish. (Not to be confused with the villainous Dr. Fu Manchu of Sax Rohmer’s novels and the films starring Christopher Lee.)

Appropriation, however, is a two-way street. To the best of our knowledge, the Chinese Linking Rings is not Chinese, it’s Italian. And today, most who perform the feat employ technique and choreography first created in the 1930s by Canadian magician Dai Vernon. So magicians, then and now, “sample” material, borrowing from each other, sometimes with credit, usually without, and almost never with compensation. My own sense is that this “creative commons” dilutes the power and promise of the craft, both within and outside the community.

As an aside, you don’t see much, if any, magic appropriated from First Nations. Perhaps that’s because their sense of magic is often rooted in nature. When Mr. Henning, for example, performed his floating ball, where a large silver sphere floated around the stage on a tour of the Arctic, he was surprised by the lack of response it generated. When he questioned community elders about it after the show, he learned that, although the audience enjoyed the performance, they believed it paled in comparison to the spectacle of the floating ball they see every day – namely, the sun, as it rises and sets. And they were right.

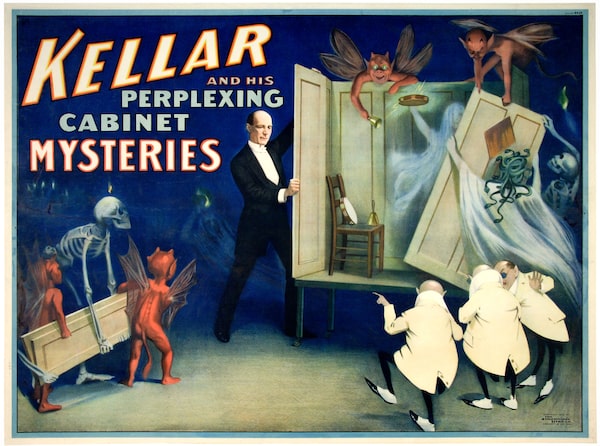

And then there’s outright theft. In the first golden age, magicians such as Harry Kellar often stole secrets through industrial espionage. Wanting the secret to the levitation, Kellar hired Paul Valadon, who had worked backstage for John Nevil Maskelyne, the inventor of the piece. Then, once he knew the secret, he dismissed Valadon from his employ.

Strobridge Lithographing Company, Kellar and His Perplexing Cabinet Mysteries, 1894.

Today you can find an explanation of how to make someone float in a few keystrokes. Spoiler alert: Most explanations of magical effects posted online are incorrect. This is not surprising. The real secrets are hard to describe because, essentially, magic is the cumulative effect of hundreds of apparently inconsequential details. These details fall within the rubric of Michael Polanyi’s concept of tacit knowledge – the hard to describe but ever so essential details that are usually transmitted through apprenticeship or mentorship.

Also, magicians lie. Believe me. We just can’t help it. By delivering false narratives with conviction and using the power of suggestion to anchor false memories into the minds of the audience, magicians, then and now, were/are purveyors of “fake news.” Take, for example, the Indian Rope Trick. In this effect, the magician causes a rope to levitate into the sky, then instructs a boy to climb up the floating rope. But, to the dismay of the magician, the boy vanishes. The magician scurries up the rope with a scimitar in hand to find the child, then chops the boy’s body to bits, which then fall to the ground! Once the magician returns to the ground, he places the boy’s body parts into a basket, then miraculously conjures the boy back, whole and alive. Talk about an effect! Unfortunately, it never happened – at least not like that, although scores of people swear they saw it performed on the streets in India. So, fake news then. Fake news now. At least, as master magician Karl Germain quipped, magic is the most honest of professions: A magician promises to deceive you, then does so. Politicians?

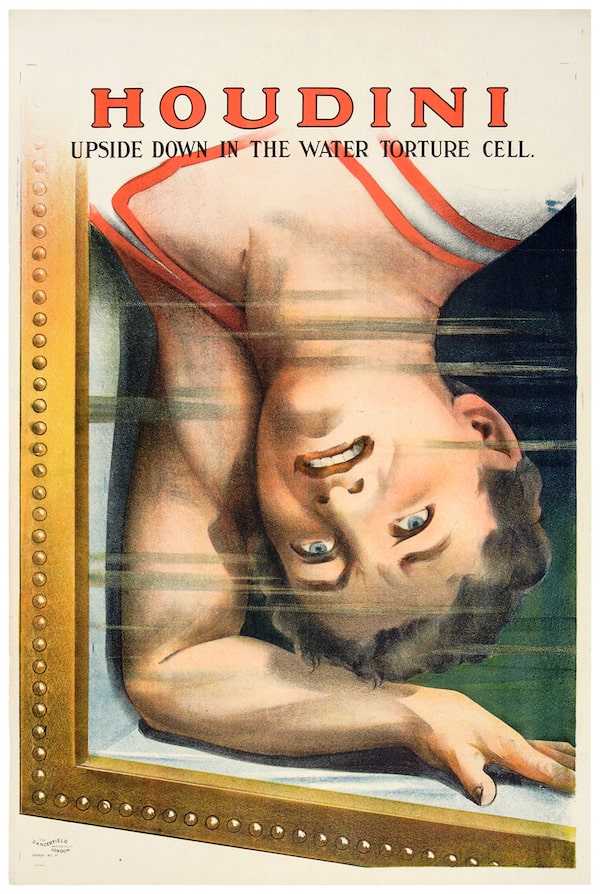

The Dangerfield Printing Company Limited, Houdini Upside Down in the Water Torture Cell, about 1915.

Master magicians of the first golden age were also masters of that era’s social media. Houdini, after being nestled beside U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt in a group shot, had the photo altered to remove the others – photo-shopping before Photoshop – then distributed the doctored photo to the media as though it were a “selfie” with his good friend, President Roosevelt.

Houdini was also the progenitor of the “flash mob.” Spreading the word that he would perform a dangerous feat, such as escaping from a straitjacket “used on the criminally insane” while hanging upside down from a flagpole atop one of those newfangled skyscrapers, Houdini would attract crowds in the tens of thousands. George Bernard Shaw once described Houdini as one of the three most famous people in the world, the other two being Jesus Christ and Sherlock Holmes – and two of them were fictitious.

Finally, here are two major differences between then and now.

Today, if a magician portrays himself or herself in a poster with an imp whispering secrets into their ear, the magician is likely to hear complaints about importing or supporting demonic spirits in the workplace. I speak from experience. Back then, the general public, or even organized religious groups, showed little concern that the devils depicted in magic posters were doing just that.

Second, there was little preoccupation with “fooling them,” as there is today. Today, most magicians present their feats as puzzles to challenge the uninitiated rather than communicate a sense of wonder or put forward a view of the beauty in the mysterious, feelings and sensations that Roger Fry and Clive Bell may have riffed on in their exploration of aesthetic emotion. But make no mistake, the best in magic does just that. Magic can evoke emotion – an aesthetic emotion, the same generated by a painting by David Milne, Emily Carr or Lawren Harris – if presented properly and if the audience is willing to take time to savour it. This is more challenging in the digital age, when people prefer answers immediately – even if they are based on false memories and narratives – rather than embark on a journey to the realization that perhaps there are some things better left unexplained.

Left: Strobridge Lithographing Company, Houdini Presents His Own Original Invention, 1916.

Middle: Av Yaga, Alexander, the Man Who Knows, 1915.

Right: David Allen & Sons Limited, The Incomparable Vonetta, about 1910.

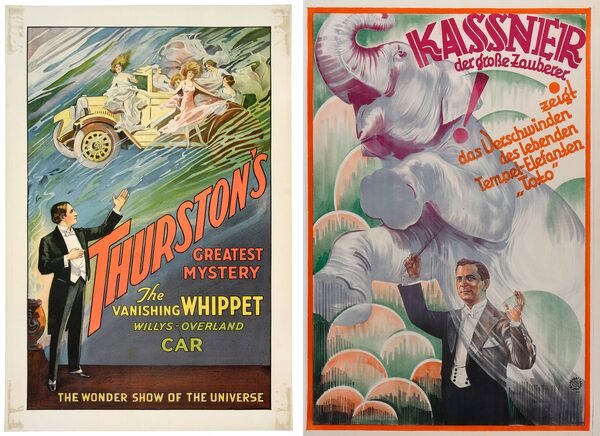

Left: The Otis Lithograph Company, Thurston's Greatest Mystery – The Vanishing Whippet Willys-Overland Car, 1929.

Right: Adolph Friedländer, Kassner, der große Zauberer, 1929.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.