Tupperware parties, introduced in 1948 and raised to a marketing art by a poor Detroit housewife in the 1950s, were one of the pioneering forms of the direct sales strategy. 'Multilevel marketing' is a type of direct sales that rewards distributors with a percentage of the sales of the new distributors they recruit.CCAD, Smithstonian Institution/The Associated Press

Ellie Flynn is an investigative journalist and broadcaster based in London. Her most recent documentary is BBC Three’s Secrets of the Multi-Level Millionaires.

In recent years, I’ve noticed a strange trend on my Facebook feed. Family members, old friends and women I haven’t seen for more than a decade are suddenly getting back in contact, asking me to join “VIP groups,” or private messaging me to buy “exciting” new products. Lipstick, clothing, face masks, nutritional supplements (and many more!) are all up for grabs for what seem like inflated prices.

These women – and it is mostly women – are caught up in the mysterious world of multilevel marketing. Also known as MLM, network marketing or direct sales, the industry has annual sales of $250-billion. These companies, whose reach has extended thanks to social media, are sweeping the globe – earning a select few millions, while costing others thousands. And, in some cases, the companies have earned their know-how from an unexpected source: organized religion.

In heartfelt testimonies, women declare they have more time for their families, more confidence – and loads more money, thanks to an “amazing opportunity” that helped them turn their backs on the nine-to-five grind and become self-made entrepreneurs. What’s more, they insist you could do it, too.

The formula seems simple enough. Join their team, follow in their footsteps – and everything you’ve ever wanted is just around the corner.

Except, in most cases, it’s not.

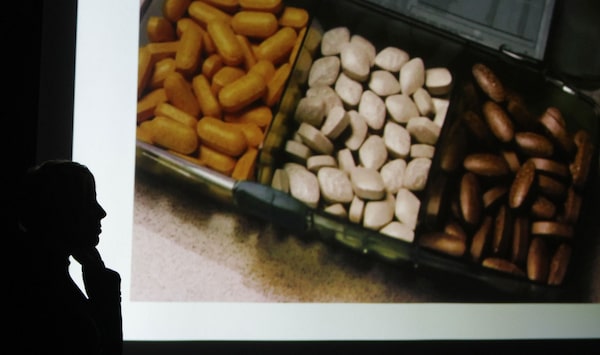

MLMs are companies that sell products through individual distributors, offering anything from makeup and essential oils to life coaching and utilities.

But delve a little deeper, and you will often find a murky underworld of predatory tactics that have led to allegations of pyramid-scheme business structures and psychological manipulations that mirror those used in cults.

While MLMs are legally operating companies, in my view, some capitalize on a grey area of law that allows them to take advantage of vulnerable people.

In my home country, Britain, there are more than 400,000 people signed up to MLMs. In Canada, this number rises to 1.3 million, while in the United States, there are more than 18 million distributors. Worldwide, there are an astonishing 116 million people involved.

Ellie Flynn, investigative journalist.Josh Reynolds/Josh Reynolds

I recently spent nine months investigating this controversial industry for a BBC documentary that took me all over Britain, across the Atlantic and into the heart of the Mormon church. I signed up with two companies, and attended a number of training events undercover for a nerve-wracking exposé that led me to many young women who had succumbed to the charms of two of the biggest MLMs, Nu Skin and Younique.

Both Nu Skin and Younique are U.S.-based cosmetic companies, with a largely female demographic. Nu Skin was founded in 1984 in Provo, Utah, and now has 825,000 sellers – known as “distributors” – in 52 countries. Younique was also founded in Utah, in 2012, and now has more than one million sellers – or “presenters” – worldwide.

Before signing up, I was struck by how secretive both companies appeared – and how vague the job specification was. I’d been encouraged to “start my own business,” yet I was signing up as part of a team and under an “upline” – the name given to the person who recruited you, and anyone who sits above them in the recruitment structure. I was given the impression I could earn thousands of pounds a week, yet the confusing compensation plans meant I was unable to work out how much money I’d actually be earning. I was promised “time freedom,” but not given an idea of how many hours a week I’d need to invest in order to make my business a success. I was simply told I could “put in as much or as little as I like,” to “earn as much or as little as I like.” If I wanted to be a six-figure earner, that was possible. If I wanted to “play around with makeup,” that was fine, too – but I still felt I had no real understanding of how to achieve my dream goal of 12 holidays a year and a giant mansion.

It wasn’t long before the message became a little clearer at both companies: If I wanted to be a six-figure earner, I needed to recruit.

From Younique, I learned about “RITA,” which stands for “recruiting is the answer.” In other words, I needed to build a team, not just sell. While I was undercover at a Nu Skin training session, a senior distributor told the group: “A lot of people get confused with this business. Because it is a beauty business, they think they have got to sell products – but actually this is a recruitment business.”

This is not a new concept. MLMs have officially existed since 1945 – when a brand of vitamin products, Nutrilite, were sold using the model. Nutrilite was eventually taken over by Amway, which used the multilevel marketing model to sell their products alongside other household items. But the idea of direct selling from representatives, without the need for a shop, dates way back to the early 1900s, with the first-ever Avon lady. Over the years, we have seen everything from Tupperware parties to Ann Summers parties using this model of sales, while also encouraging recruitment – and they always predominantly target women (in 2018, 74.8 per cent of sellers in the United States were women), with the promise of gaining financial independence.

An ad from 1961 traces the style of Avon sales agents from the 1880s. The cosmetics brand is now one of the world's largest direct-sales companies.The Associated Press

Why target women?

The decision whether to go back to work is one many new mothers struggle with, and according to a 2015 Gallup poll, 56 per cent of American moms said they would stay at home with their children if they had the chance. These business models appear to offer the perfect solution – a way of earning while staying at home. In reality, many of the women signing up are finding themselves out of pocket, or earning very little despite hours of work.

After signing up to both Nu Skin and Younique, I decided to learn more about the companies’ origins – and traced both back to a surprising community: the Mormon church.

The founders are all members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, and both companies originate from Utah, the Mormon capital of the world. Utah has more recently found fame as the heart of MLMs, with more than 100 companies originating there, and many residents believe there is a connection between the two.

Members of the church tell me they are in many ways the perfect recruits, as many serve missions around the world – in which they knock on doors to speak to people about Christ.

One woman, Geena Alger, tells me this “definitely teaches you a lot about recruitment” – and says, as a result of her mission, she was never afraid to approach people about her MLM business. Ms. Alger, who has tried three MLMs and failed to make money at any, says the companies are “exploiting” the Mormon belief system and target “young moms and those young women who want to stay at home.” Ms. Alger says young moms are particularly vulnerable, as they often feel they want to contribute to the family’s finances while also staying at home to look after their children. She added it’s a particularly vulnerable time as it can feel isolating, and MLMs offer women a chance to be part of a community.

Many people who sign up to these companies are also not aware of how slim their chances of success really are.

After a bit of digging, I found a depressing truth. Figures on the Younique website state just 0.02 per cent of presenters worldwide make the top earnings each month, but since Younique doesn’t publish earning figures, the top amount is not actually known. For Nu Skin distributors in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, 89 per cent made no commission at all in 2017.

When I reached out to former sellers to see whether they managed to achieve either the time or financial freedom so enthusiastically on offer, many of the men and women told me they had invested hours of their lives and saw no financial compensation. Furthermore, many say the aggressive recruitment they were encouraged to do drove away friends and family.

Vickie Alloway, 24, says she joined Nu Skin a few weeks before her maternity leave, after looking through her finances and thinking: “Oh my god, how are we going to survive?”

The new mom put “hours and hours” into her business, worked through the first eight hours of her 25-hour labour and continued working from her hospital bed shortly after giving birth. After six months, she had earned just £20 (around $32).

Ms. Alloway felt she had been recruited because she was pregnant, young and desperate. She realized that the only way to make money was through recruitment, and so, despite earning next to nothing herself, went on to target people in a similar situation.

Astonishingly, this drive to “target” people based on their vulnerabilities does not seem to happen by chance. In fact, it seems to be an important part of the training new recruits receive. While undercover at the Nu Skin training session, the senior distributor told us to find people’s “weak points,” and use them as reasons they should join the company.

If someone says they don’t spend enough time with their children, tell them the opportunity will open up more free time.

An advertisement from the 1950s touts the social benefits of Tupperware parties for women.National Museum of American History/Smithsonian Institution

The focus on recruitment raises some major red flags, and has led campaigners to argue some MLMs are operating almost like pyramid schemes.

Pyramid schemes are illegal across the world, but the specific laws and definitions vary from country to country. Canada’s Competition Bureau says: “Although pyramid schemes are often cleverly disguised, they make money by recruiting people rather than by selling a legitimate product or providing a service. … In Canada, it is a crime to promote a pyramid scheme or even to participate in one.”

Under both British and Canadian law, MLMs are legal – but there seems to be a very fine, blurred line separating the two business models. Stacie Bosley, an economist with a special interest in MLMs, says that even if there is a product on sale, “it can be a pyramid scheme if the emphasis is more on that recruitment side,” and advises that if a company says a way to earn more money is to recruit more sellers, “I would run the other way.”

Plenty of people actively lose cash after signing up to MLMs. Training material handed out at a Nu Skin event I attended undercover suggested becoming a “product of the products” by replacing your household items with Nu Skin products – something I worked out would cost me £430 ($700). At Younique, many people told me they felt pressure from their team to invest in all the new products and attend numerous costly training events. MLMs can drive many cash-strapped people into debt.

Perhaps the reason why so many people continue to spend time and money on their failing businesses is the message “if you just worked hard enough, you can have anything.” From an outside perspective, comprehending how someone could spend thousands of dollars on a business they are failing to profit from might be difficult, but many people say they felt compelled to continue as they were under the illusion their big break was just around the corner – and if they just tried a little bit harder, bought a little bit more or put a few extra hours in, they could have it all.

Mindset training is encouraged at both companies. At Younique, my upline went as far as to say: “90 per cent of what we do is mindset.”

At one training event, I was advised to distance myself from anyone who is negative about the industry. The trainer explained that many people “live for the weekend … If you step outside of that norm, they don’t want to see you be successful when they’re not.”

I’ve heard from multiple people who say MLMs have cost them their friends and family, and many describe these companies as feeling like “cults.”

Alexandra Stein, an expert in cults, has raised a number of concerns about the effects of the multilevel marketing industry, which may encourage distancing one’s self from friends and family who may be “holding back on your success.” MLMs have a “total belief system” mentality which can manifest as almost “religious fervour” and is consistent with brainwashing, instilling the message: “You’re going to be a loser if you don’t keep up with the program.”

Dr. Stein’s suggestion that some MLMs have a “total belief system” is based on the observation that sellers are encouraged to dismiss “negative influences” – people who challenge them or who try to discourage them from joining.

This is a phenomenon I came across many times throughout my undercover investigation. Within both companies, there was a sense that working for an MLM was the best thing you could possibly do for yourself and your family, and I felt as though anyone who questioned or denied this was perceived as misguided, wrong or in need of educating.

This “cult-like” atmosphere is exacerbated by huge conferences put on across the globe, attended by thousands of people, where successful MLMers stand on stage to give heartfelt testimonials about how their life has changed since joining. Tickets cost upward of $300 and some people claim to have spent thousands attending conferences in their home countries and abroad.

A member of an Amway sales team talks to possible new recruits at a weekly meeting.Glenn Lowson/The Globe and Mail

When I reached out for comment about my BBC documentary investigation, both Younique and Nu Skin denied any wrongdoing. Younique said: “We purposefully developed the business model to allow Younique Presenters to run their businesses at a level that makes sense for each individual … Younique Presenters do not need to build up any product inventory, as our digital platform allows customers to buy products directly from Younique.” The company went on to say, “We take compliance very seriously and have strict policies in place for our Younique Presenters to ensure adherence with all local laws, including those related to product claims and earning potential.”

Nu Skin echoed similar sentiments, saying, “We have strict policies against misrepresenting the opportunity or our products and making exaggerated claims. We also have a one-month 100 per cent, and one-year 90 per cent refund policy for resalable products to further ensure a sales leader is not financially harmed ... we are committed to strict compliance with the laws and regulations where we operate and have implemented policies and training to help our sales force comply.” Nu Skin also added that “as with any business venture, the level of success varies greatly based on factors such as a person’s goals, ambition, commitment and skills.”

As for my experience, the further I immersed myself in the world of MLMs, the more concerned I became about the lack of transparency and the distribution of wealth. There is no denying some people’s lives have been changed for the better, whether through financial reimbursement – or simply by gaining friends and confidence as part of this world, but so many seem to experience the opposite.

Of course, with any business there is a risk of failure – and some people will succeed while others don’t, but the issue with MLMs is you are consistently told you can do it, when the figures prove that the majority of people can’t.

In many ways, the structure of MLMs makes people both victims and perpetrators. If you have genuinely had success, why would you think anyone else can’t? If you’ve been told everything you’ve ever wanted is just around the corner, why would you warn recruits you’re yet to make any money?

I believe those at the very top should be held responsible for making these risks heard loud and clear before people sign up. But losing recruits at the bottom puts their whole business structure into jeopardy, so I doubt they are jumping at the chance of transparency.

Tighter regulations are needed, which force companies to publish realistic earning potential to any new recruits. This would mean companies publishing earning figures for those signed up at all levels, and encouraging distributors to be honest about what they are receiving in income, after expenses. It should also be made clear that your income one month does not dictate your income the following month, and earning potential should be tracked across the year.

With more transparency, I believe fewer people would invest so heavily. There should also be rules on how much emphasis can be placed on recruitment. If the companies are encouraged to focus primarily on sales, I believe there would be less room for exploitation.

These days, when I scroll through social media, I can spot an MLM post a mile off. What I once would have seen as a normal selfie is in fact an advert for a new product. What I would have once interpreted as an old acquaintance getting back in touch I now realize is a recruitment drive. Any time I see the words “exciting opportunity,” “work from home” or “message me for info,” alarm bells go off. Perhaps I’ve become cynical, but I can’t help but wonder what the intent behind those messages is.

In an era when we are all encouraged to “fake it until we make it,” how do we know who is telling the truth?

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.