In 2012, a beanie-clad protester smokes cannabis at a 4/20 rally on Parliament Hill. In 2018, an employee wears gloves sorting through harvested cannabis plants at Hexo Corp.'s facility in Gatineau, Que.Patrick Doyle and Chris Wattie/Reuters

Part of cannabis laws and regulations

Alan Young is professor emeritus at Osgoode Hall Law School and co-founder and former director of Osgoode’s Innocence Project.

I started practising criminal law in 1984. I felt relieved that I was not starting my career within the dystopia of repression and fear prophesized for that year by George Orwell. However, I quickly discovered that the war on drugs had reached a fevered pitch by 1984, and that this futile war was fostering repression and a slow movement toward the Orwellian society of rampant state surveillance. Cannabis was still being demonized as the “smoke from hell” and billions of dollars were being wasted manufacturing cannabis criminals out of ordinary, law-abiding and productive citizens. Orwell’s prophecy may have been just a literary vision, but as a young lawyer, it seemed to me that only in a world of science fiction could a plant become public enemy No. 1.

Not long after my career began, I was counsel in a case involving a large-scale conspiracy to import hashish. One of the accused, Rosie Rowbotham, a well-known advocate for cannabis reform, had not made bail owing to previous cannabis convictions and he sat alone in the prisoner’s dock. One day at trial, the Crown entered a large brick of hash as an exhibit and, as is customary, the exhibit was passed to the defence lawyers and their clients for inspection. The Crown continued with his examination of a witness until he stopped in the middle of a question to advise the judge that “Mr. Rowbotham is ingesting the exhibit in the prisoner’s dock.” In his continued and relentless defiance of the law, he ate the hash to send a message and make the day in court more enjoyable. As Rosie flashed a Cheshire grin, with specks of brown hash on his lips, the other cannabis conspirators filled the courtroom with uproarious laughter. But the laughter was short-lived. There is nothing funny about criminal law. As the song goes, “I fought the law and the law won,” and everyone involved in the conspiracy went to jail, with Rosie being sentenced to 18 years as the ringleader.

I have seen many good people destroyed by our punitive drug war. I have seen long years wasted in prison for harmless pot crimes; families torn apart, with children being seized from pot-smoking, caring parents; young men beaten while being arrested for smoking a joint in public spaces; model workers being fired from jobs for private lifestyle choices; and homes razed, and homeowners shot, during aggressive police raids. Indirectly, we were all harmed by this war, as billions of dollars were diverted away from the pursuit of true predatory criminals. As a civilized society, Canada has spent far more money on drug-law enforcement than on the investigation, enforcement and prevention of serious crimes of violence. The war on drugs made us less safe and secure.

While people are still healing from the ravages of this war, the tables have turned and, in a few days, everyone of age can get legally stoned. Licensed cannabis producers, drug stores, provincial governments, labour unions, marijuana dispensaries and aggressive stock brokers all want a share of the legal market. Casting a dark shadow over this emerging new market is the sinister irony that former police officers and other public officials, who were responsible for sending thousands to jail in the past for selling pot, are now poised to make millions for doing the very same things as the people they busted. The government should be handing out pardons to the cannabis criminals and not licences to those who hunted these so-called criminals.

How did we get from the scary days of 1984 to the Green Rush of 2018? The historical record is a testament to the stupidity and mendacity of government. With little fanfare, marijuana became a prohibited substance in Canada in 1923. Even though it had been used for sacramental, medicinal and recreational purposes for 10,000 years, when Parliament decided to criminalize marijuana use, few members of Parliament had even heard of this drug. In fact, in 1923, few Canadians were using it and, until the explosion of the counterculture in the 1960s, there were only a handful of recorded convictions for the use or sale of marijuana. After 95 years of chasing the cannabis criminal, we have seen consumption of marijuana skyrocket, with an estimated four million Canadians indulging in this “vice,” despite the presence of our draconian criminal sanctions.

A headline from The Globe's edition on April 24, 1923, notes the final passage of federal anti-drug legislation that, among other things, made cannabis illegal in Canada.The Globe and Mail

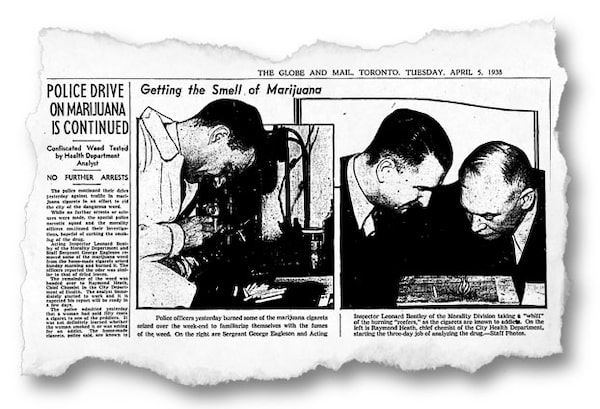

In order to justify the inclusion of marijuana as a prohibited substance in the 1920s, public officials and media representatives were required to construct an outrageous “dope fiend mythology” to frighten the masses and convince them that they should look to the government for protection. Judge Emily Murphy, the first female judge in Canada, wrote in her book The Black Candle (1922) that “persons using this narcotic … lose all sense of moral responsibility. … While in this condition they become raving maniacs, and are liable to kill or indulge in any form of violence to other persons, using the most savage methods of cruelty.” Similarly, Maclean’s magazine reported in 1938 that marijuana could “send a large proportion of the Dominion’s population to the insane asylum.” Most of the hysterical claims made by state officials and media representatives were driven by racism and xenophobia. It was widely believed that all intoxicating substances, except alcohol, were being used by immigrants and visible minorities as a weapon to destroy the purity of white society.

A clipping from The Globe and Mail on April 5, 1938, notes an anti-drug crackdown by Toronto police, and shows senior officers igniting some joints so they could learn to identify the drug by smell.The Globe and Mail

Although there are few people today who believe this hyperbolic drivel, there still remained a sense among Canadians that Parliament would not retain the prohibition unless there existed some significant danger from marijuana use. However, evidence of significant danger simply did not exist, yet the government continued to spread falsehoods in support of its policy. The fabric of Canadian society is not now, nor had it ever been, in peril as a result of many Canadians freely choosing to intoxicate themselves with this mild psychoactive substance; when I was doing defence work in 1984, however, government officials often told courts that my clients should be punished harshly as their actions did threaten the fabric of our society. We clearly have far more to fear from problem drinkers than we do from stoners who zone out to Pink Floyd; but throughout the years of my career, officials spread the false gospel that we have more to fear from pot smokers than pot-bellied beer drinkers. The government is complicit and responsible for knowingly spreading misinformation to support a failing war. Government used science as a tool of propaganda and intentionally fuelled a moral panic to justify huge fiscal expenditures purportedly designed to wipe out marijuana use.

It is not entirely clear why the government changed its tune in the past few years. Both federal and provincial officials still project some doom and gloom when speaking of marijuana use, but this is a far cry from the rabid and hysterical claims made just a few years back. What changed?

Twenty years ago, I predicted that cannabis would be legalized when governments and corporate entities came to understand the untold monetary treasures to be reaped upon legalization, just as large-scale gambling was legalized in the late 1980s to reap billions of dollars in tax revenues. Money is a key component, but this is only part of the picture. Based on my personal experience, I saw other factors enter the equation. For the past 25 years, out of a sense of personal and professional outrage, I have worked to change our archaic legal approach to marijuana and, having little faith in the political process and its partisan posturing, I turned to the courts. From my perspective, there were three significant legal or judicial events which paved the way for legalization and a renaissance in cannabis culture. I had the honour and privilege of being able to initiate all three events.

The first significant event was a successful constitutional challenge of the “drug literature” prohibition in the Criminal Code in 1995. This law prevented the sale of any literature that advocated or promoted illicit-drug use. For decades, the government had controlled the (mis)information about cannabis and, with the fall of this prohibition on expressive freedom, cannabis advocates could re-enter the marketplace of ideas. Magazines such as High Times and Cannabis Culture flowed into the market, as did grow books and scientific and political publications, which all called into question the wisdom of government policy.

The second event was a 1997 constitutional challenge to the marijuana-possession offence. The challenge was dismissed, but more significantly, the headlines in most mainstream newspapers highlighted the trial judge’s finding that “marijuana is relatively harmless.” Although the law survived this challenge, there was finally an affirmation from a non-partisan public official that the government had exaggerated and distorted the risks associated with the use of marijuana.

The third significant event was a series of cases, between 1998 and 2000, which established that marijuana had therapeutic value, and that the law violated the constitutional rights of patients by preventing them from accessing this medicine under threat of punishment. As a result of these medical cases, the government was compelled by judicial decree to allow patients, and their designated caregivers, to grow their own.

Winnipeg, 1999: Gavin Whittaker smokes cannabis on the steps of the Manitoba legislature at a decriminalization rally. By the end of the 1990s, legal precedents had begun to shift Canadians' attitudes toward the drug.JOE BRYKSA/The Canadian Press

When the dust settled on these three legal events, the fabric of Canadian society had changed. Pro-cannabis literature abounded, the state-sponsored mythology of harm was eroded and consumption rose to millions, with tens of thousands of people legally growing their own marijuana. The plant went from being demonized to normalized and cannabis culture moved from the underground to the mainstream. The government no longer controlled the discourse and the state was finding it increasingly difficult to justify its policy and expenditures in support of this failing policy. So, in 2003, a Liberal government under Jean Chrétien proposed depenalizing marijuana possession (i.e., no jail but still exposure to arrest and a criminal record), but quickly abandoned this half-baked reform when the Americans threatened to tie up trucks at border crossings.

Although our government was scared away by American intimidation, this did not stop the rapid expansion of cannabis culture in Canada. Like Starbucks popping up on every street corner, numerous medical and recreational dispensaries could be found in most urban centres. Online sales skyrocketed and master growers flooded the market with newly hybridized strains. The police lost their enthusiasm for enforcing the cannabis laws as they had bigger fish to fry, and they simply could not keep up with the growing numbers of pot consumers and producers.

Even though it was clear the government was losing the war on cannabis, in the late 2000s the Conservative government under Stephen Harper tried to resuscitate this dying policy. All talk of reform was replaced by talk of minimum sentences and tougher laws. But then American states, starting with Colorado and Washington, legalized and the U.S. federal government did nothing. Suddenly, the world could change because the United States was willing to change. Without fear of American threats and retaliation, there was absolutely no reason for us not to move down the path of legalization. But Canada needed to put an end to the Harper regime to move in this direction.

Oct. 20, 2015: Justin Trudeau, then Canada's prime minister designate, waves to supporters on election night with his wife, Sophie Grégoire-Trudeau.Kevin Van Paassen/Bloomberg

This happened in 2015, when Mr. Harper was ousted and legalization became more than a pipe dream. Moral panic was replaced by market planning. This much we know, but it remains less clear what the underlying rationale and objective was for the Liberal government under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in overturning a 95-year-old mistake. There are three basic types of justifications for a government decision to put a legal stamp of approval on previously condemned behaviour. First, there can be a personal justification. If politicians were potheads, the law would have changed years ago but, even though some, or many, have partaken, none had the courage to admit to inhaling. So it is clear the law did not change because our elected officials cherish good kush.

Second, there can be a principled justification for legalization – that people have the right to make autonomous and independent choices with respect to mind-altering substances. I subscribe to this principle, and although it needs further elaboration to be coherent, there is no reason to elaborate because this was not the basis of the Trudeau government’s decision to legalize. On the road to legalization in the past few years, no one has talked about autonomy and the right to make fundamental decisions of a personal nature without paternalistic state intervention. So it is also clear the law did not change on the basis of the principle of maximizing liberty and autonomy.

The Trudeau government’s decision to legalize clearly falls into the third category of justification – pragmatism or utility-based thinking. There is nothing glorious about this way of thinking. It is a simple cost-benefit analysis. It is just the government throwing in the towel on the basis that it believes it is no longer worth the time and expense of waging a failing war. The cannabis world had overgrown the government and it was time for the government to concede defeat. To sweeten the pot of pragmatism, the government was also highly motivated by the alluring revenue projections and the hope of stimulating the economy. I may find the pragmatic and corporate underpinnings of legalization to be crude, and a far cry from my vision of decriminalized Dutch-style cannabis cafés, but I am elated that Canada has become an international front runner in overturning the American-driven war on cannabis. Nevertheless, reliance upon a crude economic justification for changing a law which in the past has destroyed lives leaves the government with some conceptual conundrums it has failed to address.

Vancouver, 2018: An employee holds a container of cannabis at Buddha Barn Craft Cannabis.JONATHAN HAYWARD/The Canadian Press

The government lost the war and it is trite to say that usually the spoils go to the victors, not the losers. In this case, the government remains steadfast in its belief that it bears no responsibility or accountability for the damage done to the manufactured cannabis criminals. The government has declared an armistice without conceding that a mistake has been made and without acknowledging that marijuana is, indeed, “relatively harmless.” The government sees no shame in continuing to disseminate discouraging and negative information about marijuana while seeking to profit from the sale of this product. If marijuana is safe enough to enter the legal marketplace of available intoxicants, then the government should admit it made a mistake and pay reparations.

The first form of reparation should be an automatic pardon for every Canadian with a criminal record for cannabis possession. Now that the government is reaping an economic benefit from pot it should have the decency to erase the stigma it placed on people in the past, which in many cases would have limited these people’s economic opportunity. I am shocked that this does not appear to be on the legislative agenda accompanying legalization.

The second form of reparation is more in the nature of a plea for rationality and forbearance from repeating the mistakes of the past. Under the Trudeau government’s pragmatic form of legalization, the criminal law will still be applied to those who are not licensed. In many ways, this looks like the state using the criminal law to erase the competition. Those who will continue to live in the underground market cannot be considered criminals solely for running the very same business operations now being sanctioned and exploited by the government and corporate Canada. Being in possession of more than 30 grams of cannabis, and making small-scale sales, will still be considered criminal acts in our “legalized” world, but in a regulated legal market, these activities should be considered akin to fishing without a licence. Once a government gives the legal seal of approval to an activity, it then loses the moral right to condemn and criminalize the renegades who operate without a licence.

I could go on to discuss other conceptual pitfalls and problems with our government’s law-reform efforts but I do not want to rain on the parade. I do bemoan the fact that pot has gone mainstream and may be losing its countercultural allure, but it is more important to celebrate the fact that a significant step has been taken in the rectification of a tragic mistake. This mistake cannot be fully rectified, however, when the government continues to criminalize inveterate cannabis users who will refuse to abandon their old ways after Oct. 17, 2018.

Many will not abandon their old ways if the corporate takeover of cannabis cannot produce good pot. For this legalization experiment to truly succeed, the corporate world has to unite with the underground world. This has yet to happen seamlessly and I worry that the Canadian model of cannabis legalization will lead to a marketplace of mediocre marijuana. Earlier this year, I was asked to provide my opinion on the quality of 12 different strains being produced by six different licensed producers. I was shocked to discover that only two of the 12 strains were good enough to compete with black-market pot, and six of the 12 strains had a mothball taste that rendered the pot so noxious it was impossible to smoke. This is not an auspicious start.

I applaud the government’s effort to do the right thing and am also personally gratified that I played a small role in this change. Sadly, after all the fighting and all the sacrifices made in the past by those who loved the plant, I am left wondering whether our legacy will be to have left cannabis culture in the hands of a corporate world that does not know how to get Canadians high.

CHRIS WATTIE/Reuters